Wasteland Wrap-up #51

My new book, Amis on "Thinkability," del Toro's Frankenstein, a strange dream...

On Monday I participated in a “virtual roundtable” for the Council on Foreign Relations about nuclear history, presidential sole authority, and A House of Dynamite with Garrett M. Graff, who is one of those writers whose productivity and prolificness is already impressive, but verges on the annoying once I realized we were the same age. But he is in fact quite lovely and the discussion was enjoyable and so I cannot hold his abilities against him (to my annoyance — with myself).

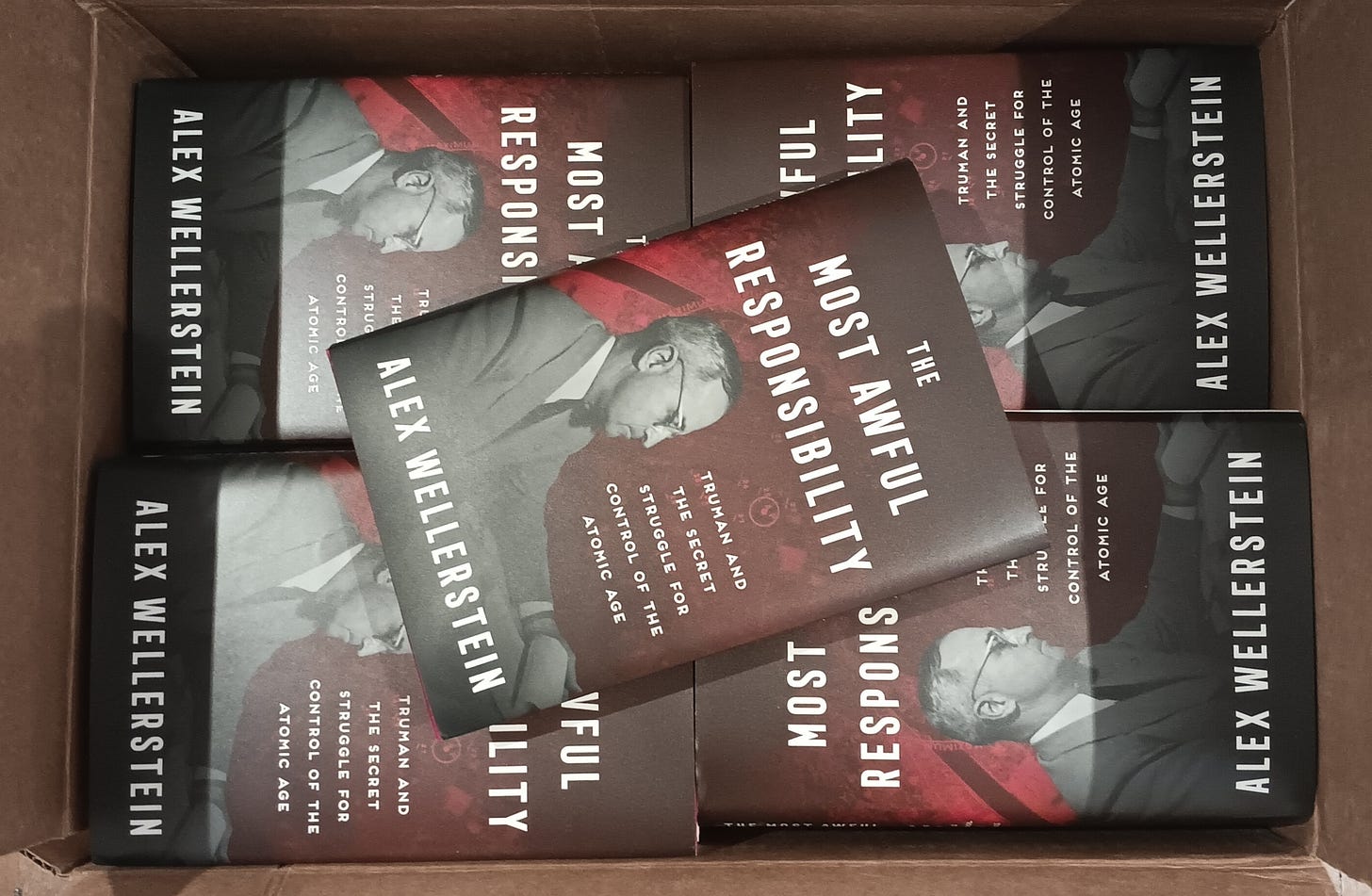

But this week, I was excited to receive my author’s copies of my new book, which is available for sale on December 9, 2025. Behold:

You should not feel shy about pre-ordering a dozen copies or so for all of your friends and family, perhaps.

Joking aside, I am happy with how it looks, although I am afraid to actually read it, as I know that the minute I do I will spot some kind of typo or mistake that somehow never got caught or corrected. (There is a joke I have seen around, which says that if you want to find typos in your manuscript, simply publish it, and then every page you open to will contain one. This is basically what it feels like.)

I will be posting some more about the new book — The Most Awful Responsibility: Truman and the Secret Struggle for Control of the Atomic Age (HarperCollins, 2025) — in the coming weeks, as we get close to the launch. Along with a few other events I am doing for it, I am thinking of having a sort of virtual book talk/Q&A on here to you special subscribers, should there be some interest in that.

In its most basic form, the book is an “atomic biography” of President Harry Truman, covering his earliest knowledge of the Manhattan Project through the end of his presidency (and a bit beyond) in 1953. It is very much focused on what Truman himself thought about the atomic bomb — when he did think about the atomic bomb, which was not always — and how his own individual, often idiosyncratic, emotional, and moral beliefs impacted the creation of early US atomic policy.

What did Truman know and when did he know it? To what degrees was his “knowledge” partial, deep, and accurate? To what degree did Truman participate in early atomic decision-making? What legacy did Truman specifically have on the use and non-use of atomic weapons? Those are the kinds of questions the book is aiming to answer.

If you have read some of my other writing on Truman and the bomb already, you might have an inkling of what a different perspective I have on all of these questions than most of the existing historical and political science literature, but the full book charts newer and deeper ground on every point. If you haven’t read my writing on Truman, oh boy, are you in for some rawther big claims that I make (and try to substantiate) about Truman and the bomb — my reading of Truman is quite different from the standard one, in ways that will probably annoy both people who lionize Truman and people who demonize them in equal measure. Tantalizing? Perhaps, perhaps…

I have been doing some other interviews, unrelated to the book, on matters relating to nuclear war, nuclear testing, and so on. One of them was on The Naked Scientists, a BBC podcast, on 80 years of nuclear weapons. My segment was about some of the history of weapons developments and a bit on the different types of nuclear weapons that exist or have existed. As I am not a scientist, I was fully-clothed while recording it.

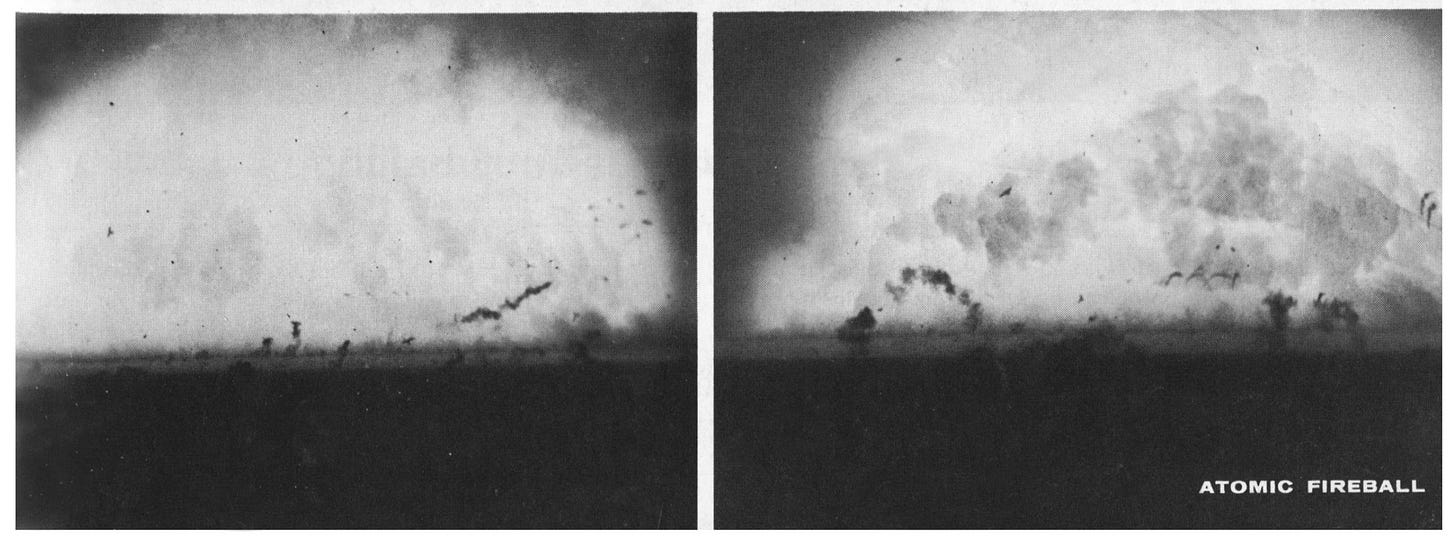

In my segment, I mentioned that there are photographs showing birds being ignited by a nuclear explosion. Here are the photos in question:

This is from the cover of Science, vol. 138, no. 3539 (October 26, 1962), which included an article on the brightness of atomic explosions. The relevant text from the article:

An interesting effect of the light from an atomic fireball is shown in the series of prints (cover photo) which were taken from motion picture film made during one of the Eniwetok tests in the Pacific. The device was detonated at night when the birds of the island were roosting in the trees and bushes located between the camera and the point of detonation. With the appearance of the light from the fireball, which at this distance was many times that of the noon day sun, the birds were suddenly awakened and took to the air. Because they were between the camera and the fireball, their silhouettes showed clearly on the film.

The time required for them to fly above the tree tops was about the same as the time for the maximum delivery of the thermal radiation pulse. At this time, the intensity of thermal radiation was sufficient to ignite the tail and wing feathers of the black birds. As their feathers burned, they could no longer remain airborne; their trails were marked by curving puffs of smoke as they fell to the ground. These trails are visible in the last two prints of the series. [above] In the motion pictures, it is possible to detect a few birds which remained airborne and continued on their way. These are the white-feathered ones. The difference in the thermal effects on these two classes of birds is due to the differences in the absorption of thermal radiation. As with sunlight, dark and especially black objects are heated more than white ones, and in this case the energy levels were just sufficient to ignite the feathers of the black terns and not the white ones.

I would categorize this more as “disturbing” or “horrifying” than “interesting,” personally.

For Doomsday Machines this week, I wrote a bit about one of my favorite pieces of nuclear writing, Martin Amis’ essay “Thinkability,” which served as the introduction to his collection of short, nuclear-related stories, Einstein’s Monsters (1987).

For those who are “paid” subscribers, I will include a link to a well-formatted version of Amis’ essay below. It has so many lines that I think about frequently, notably: “The man with the cocked gun in his mouth may boast that he never thinks about the cocked gun. But he tastes it, all the time.” Wow and yikes.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Doomsday Machines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.