Wasteland Wrap-up #55

Giving a talk this week, reflections on two recent deaths, complaining about AI slop, fallout dose scale thoughts...

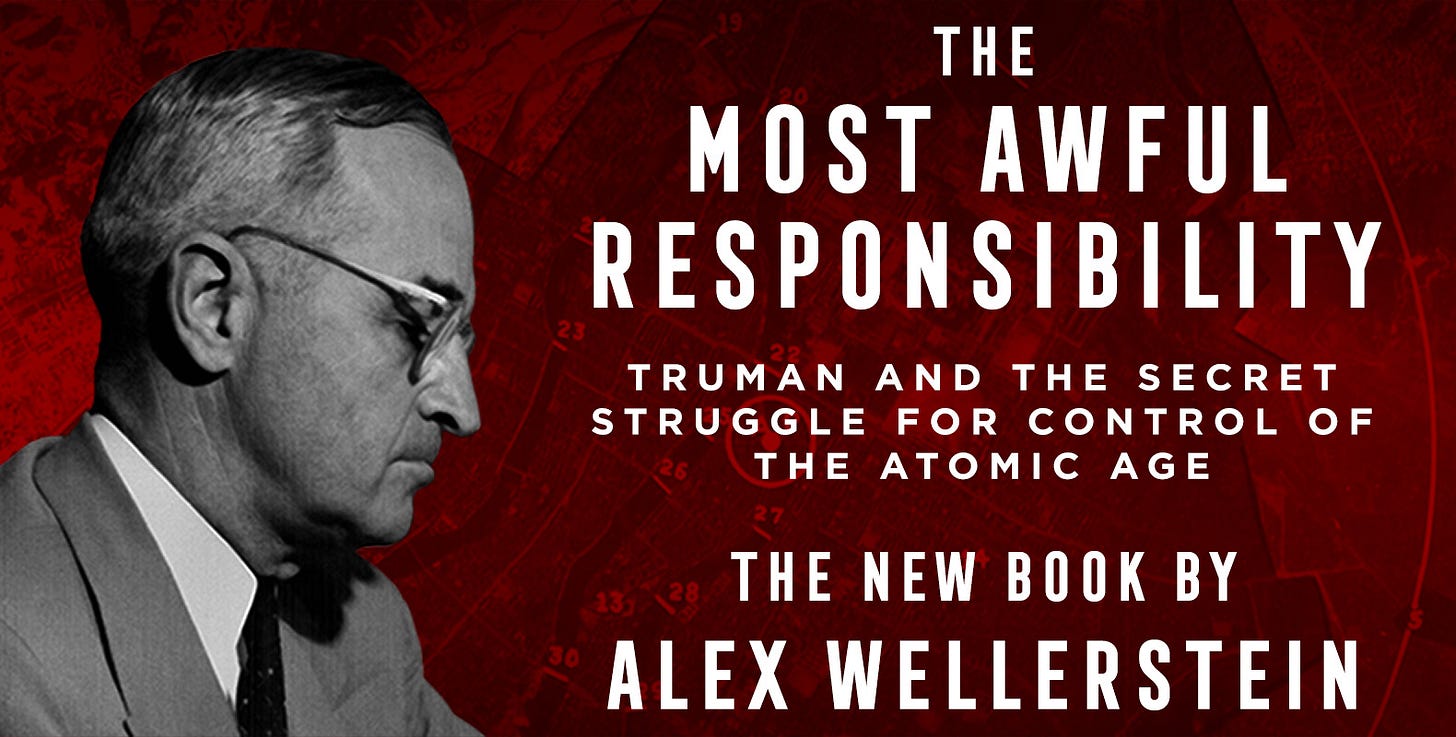

So my new book came out last week! Just in case you somehow missed it!

If you are interested in seeing me talk about the book with two other historians, on Tuesday, December 16, 2025, at 12-2pm ET (18-20hr CET), I will be doing a hybrid talk/conversation as part of the Nuclear Knowledges seminar series, at the Center for International Research, Sciences Po, Paris, on December 16, 2025 at 12-2pm ET (18-20hr CET). The event is open to the public if you happen to be in Paris, but it will also be live-streamed on Zoom. Here is the event link, and here is the registration (“inscription” in French) link that you will need to use for the Zoom link.

Releasing a book is both exciting and anti-climactic. The actual day of release doesn’t do all that much for the author. You don’t get sales information in real-time, and even if you did, it’s not clear it would tell you all that much. At the same time, you’re also trying to gin up as much interest as possible. I even put a very embarrassed little ad on NUKEMAP for my book that deletes itself after a couple of seconds.

I’ve put up a first tranche of documents from the book — mostly covering the WWII period — on my website for it. I am planning to put up some more documents in the next week (and the next week after that, etc.). It takes more time than you’d think to select, touch-up, and write-up each document.

As I was doing it two weeks ago, I kept thinking, “I don’t really know how Bill Burr does this, this is so much work,” in reference to my friend and colleague Dr. William Burr of the National Security Archive at Georgetown University, who has for decades maintained wonderful “electronic briefing books” on a whole number of topics, including nuclear weapons.

Having just been thinking about him, it was shocking to hear on Friday that Bill Burr had passed away. Bill had been battling cancer for years, which I did not know about — he apparently didn’t like to talk to people about it, which I can respect, even if it makes this kind of news completely shocking to those who did not know.

Bill was just a wonderful guy. I don’t remember when I first met him — it must have been around 2008 or 2009, when I first visited the National Security Archive as part of my dissertation research. Bill was always tremendously generous as a person and a scholar, always willing to share documents, give assistance/advice, and solicit views for inclusion in his briefing books. We collaborated on a number of things behind the scenes over the years regarding nuclear history, including having several meetings with representatives from the Marshall Islands about restoring databases that the Department of Energy took down relating to the testing there.

Bill’s persistence in unearthing new documents had a major impact on the type of nuclear history done over the last two decades. The fact that he always made these documents fully accessible and public was a core part of what made him unique as a scholar, and as a builder of scholarly resources. I’ve taken a lot of inspiration from Bill over the years. As a person, he was just lovely to be around. This tribute to Bill by James Graham Wilson gives such a better sense of this than I can express.

I looked in my e-mail and saw I had last been exchanging messages with him in September, which seems like just yesterday. Hearing he had died was just totally shocking to me, a real punch in the gut.

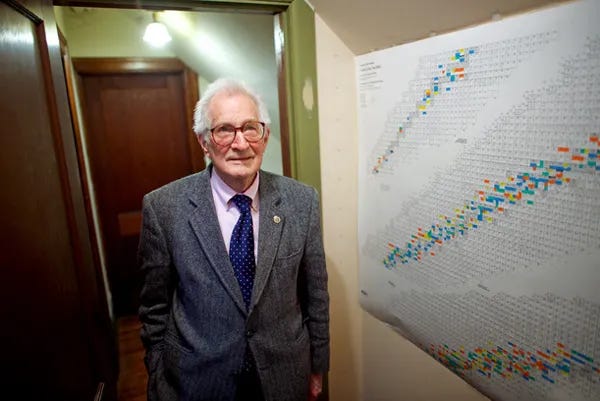

While looking for more information on Bill, I also stumbled across the fact that another nuclear person I knew had died last week: the physicist Kenneth W. Ford. Ken lived a very long and fulfilling life — he lived to be 99 and a half! — and wore a number of different professional hats. I knew him because of his work on Project Matterhorn-B at Princeton, which worked the hydrogen bomb in the early 1950s (“B” was for “Bomb”) under the oversight of John A. Wheeler.

Ken came to me circa 2014 or so while he was working on a book, Building the H-bomb: A Personal History (2015). It is part memoir, part history book, part technical discussion. Most of its technical nature concerns the work that was done before the invention of the Teller-Ulam design for thermonuclear weapons; it has some of the best descriptions of the physics of the so-called Classical Super, and the mindset behind those physics, that I have seen. What Ken wanted me to help with was the fact that everything he was writing he knew had been declassified, or at least written about, at some point, and so he needed the footnotes that would show he was not releasing classified information. Which I helped him with.

He then submitted it to the Department of Energy, who disagreed that all of it should be published — not a total surprise, I would say, as their guidance then and now is that just because something is known does not mean someone who once had a security clearance should be saying it, as that “confirms” it. In the case of 75-year-old physics, particularly about a weapon that didn’t work, I think this is a little bit silly, but I’m not the one who once had a security clearance. Anyway, Ken published the entire thing anyway, and then used the attempt by the DOE to censor the book as a way to get more attention for the book, as I wrote about at the time. The DOE probably could have gotten Ken into trouble but I think they assumed that trying to prosecute octogenarians for publishing things that were decidedly in the open literature would be a bad case.

Ken stayed in touch over the years, and would occasionally write up technical answers to questions I had. Often they would convince me that I should try to avoid getting too technical on certain subjects, not because they were dangerous, but because I could feel I was wading into territory I did not really understand well-enough to write about! (Like “electron temperature.”)

Anyway, these are the thoughts that have occupied me the last few days — coming to terms with these losses. They are of a different character from one another, as Bill’s seems quite unexpected and Ken’s is just more bittersweet.

All of which feels like really bad framing for plugging the interview I did with the wonderful (and very much alive!!!) Cheryl Rofer for Doomsday Machines this week, on her +30 years working at Los Alamos National Laboratory. The interview touches on a number of topics, including the nature of the work at the lab while she was there, the issues with gender that she encountered there, and — a personal favorite of mine — Cheryl’s memory of the Cuban Missile Crisis as a teenager.

Cheryl is quite lovely, and when my wife and I would go to New Mexico, we would always want to make sure we had time to see Cheryl (and her cats!) in Santa Fe. So I have been wanting to interview her for the site for awhile, as she is a repository of just a vast amount of personal experiences about the lab — our interview really just scratches the surface.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Doomsday Machines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.