Working at Cold War Los Alamos

A conversation with the chemist Cheryl Rofer about her over thirty year career at Los Alamos

Doominations is a series of interviews with people whose life experiences or work in some way touches on the questions of interest to the post-apocalypse.

Cheryl Rofer has been a friend of mine for many years now. She worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1965 until 2001 in a number of roles, including working on laser isotope separation, environment cleanup and hazardous waste disposal, and worked with Estonia and Kazakhstan to clean up environmental problems left by the Soviet Union. She lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico, for many years, and is the best nuclear tour guide over there that I know. She actively posts at Nuclear Diner and Lawyers, Guns, and Money. I thought it would be important and interesting to ask her about her time at the lab, and especially on being a woman at the lab in the high Cold War.

When did you start working at the lab and why? Why there out of all places?

Okay, well, this was back in 1965, and things were really different in 1965. So the simple answer is that my husband got a job at Los Alamos and I went along.

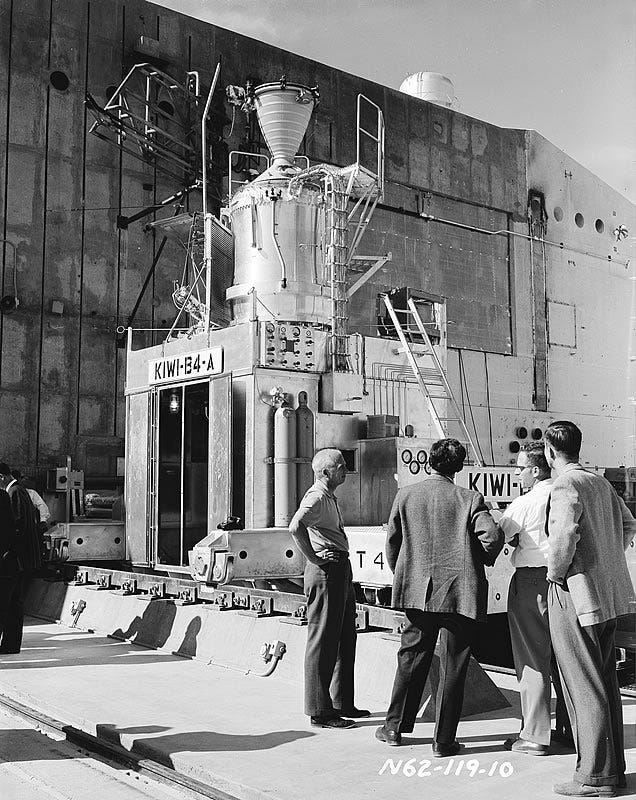

He was a ceramic engineer, and he was hired to work on the fuel elements for the Rover rocket reactor. I had a master’s degree in chemistry. I have never been a great fan of school and I dropped out with a master’s degree. Which was probably a mistake, although ultimately it worked out good enough.

There was just a whole lot I did not know about a career and all of that. But the night before we reached Los Alamos, we stayed in Santa Fe. And I cried because I didn’t know what my future was going to be.

Was there any discussion about him taking the job at Los Alamos?

Not really. That was very much assumed at the time. And the 1960s were just what is now an incredible time for people in science getting jobs. I mean, we did the grand tour. Several corporations in various places paid for both of us to come for interviews.

I remember going to Connecticut, I think it was United Technologies, and we went to Los Alamos, and there were probably a couple of others. And that was just the way it was back then. The companies had a lot of money for science graduates and they were bringing us out there.

Now, being the trailing spouse, for some of these interviews, it was just a matter of I was there, and I wasn’t part of it. But I do remember the United Technologies interview, because the wife of the person who was interviewing my husband toured me around and said, “now this is the part of town you would live in.” [laughs]

I had also applied for a technician job at Cutter Pharmaceuticals. And what they said was, you were the best applicant for the job, but the man you’d be working with can’t see working with a woman. So that’s how it was back then.

So then you also were at Los Alamos.

You know, one of the subsidiary good things about the Lab was that they had this ethos of hiring the spouses as well, which was left over from the Manhattan Project. It was easy when I got to Los Alamos for them to slot me into a technical writing job because I was a wife and that was the kind of job I had had before. So I got a job in one of the reactor groups. This was a group that was mainly calculational, and they were working on things like loss of coolant accident. So that was actually good in a way because I learned a whole bunch about reactors.

In the 1960s, Norris Bradbury was trying to turn the lab around a little bit, so that it wasn’t exclusively working on weapons. They were working on geothermal energy, and there was also some interest in solar, and of course, they had the Rover [nuclear rocket] program.

But around 1970, there was a real crisis at the lab, because reactor programs were just being stopped across the Department of Energy. And this is kind of an interesting time that hasn’t really received a lot of attention. I did a little bit of research on it and it turned out that the person who was in charge of reactors at the Atomic Energy Commission decided that we didn’t have enough uranium and so we needed to focus on breeder reactors. So he cut out everything else that was being done on the reactors, and that included Rover. It included what the group I was with was doing in terms of loss of coolant accidents. And it just stopped overnight.

It was the first big shock to the laboratory in terms of losing money. People were really displaced. My group was dead, but my group leader very kindly — he thought anyway — got me a job in one of the explosives groups as a technical writer. And about that time, I was getting a little bit tired of that. And I was sharing an office with a young man who had a bachelor’s in chemical engineering, and he was getting to do fun things and I was getting to do documents.

So I quit and I put my attention to developing a chapter of NOW at Los Alamos.

This is the National Organization of Women?

Right. This was in the days of consciousness raising and we had consciousness raising groups. And Harold Agnew [the director after Bradbury] was really not happy at all to have a chapter of NOW in Los Alamos, because he felt it was doing everything right, that the lab was perfectly fair — because it hired wives as well as husbands.

I mean, you know, people just had, a particular mindset back then, which is different from what we expect now.

Anyway, so I was out of the lab for a couple of years, and then I decided that if I was going to be a scientist, I guess it was going to have to be at the lab. My husband was still working there.

They were developing a laser division, which was looking at both laser fusion and laser isotope separation. And there was a job advertised that looked perfect for me, but it was in my husband’s group. And back then they had nepotism rules that prevented putting husbands and wives in the same group. So I couldn’t apply for that.

But they did have an Equal Opportunity Officer by then, and so my husband and I went to him and we said, well, we’re going to have to get a divorce. And he said, he said, “would you live together?” And we said, yes — which was not done back then. And he said, “don’t do anything.” And within a few days, the University of California [who managed Los Alamos] no longer had the same nepotism rules, which was kind of convenient.

It was Bob Bussard who hired me. This is Bob Bussard of the Bussard Drive. He was the deputy division leader. And he was kind of a wild man. And he said, when he hired me, I’d rather have you working for me than against me.

So that was how I got into the laser division and started doing some cool things. I was in the systems analysis group and we did a little bit of lots of things and that was a lot of fun.

What exactly made you feel that Los Alamos needed a chapter of NOW in the 1970s?

Everybody needed chapters of NOW then. It was just a thing.

They were quite happy to have me as a technical writer, despite the fact I had a master’s degree in chemistry. There were also little things like that.

I can remember one colloquium, with one of their famous biology guys on trips to Mars, spaceships to Mars, because that was what the Rover reactors were for. So he’s talking about space flight to Mars and possible radiation doses. And of course, he added, we’d need to have some women along on the trip because ha ha ha ha, you know why. And I wrote a little note to Norris Bradbury about that. He was not pleased. But it was, you know, just really unpleasant and denigrating and kind of indicated a bad attitude.

And then a little later, after Bob Bussard had hired me back in, I was doing these experiments with plutonium and uranium. This was when they still had the DP site plutonium facility. They had only a men’s change room, but they said they were going to have a women’s change room and they were going to have it soon. They were working on it and they were working on it. And I wanted to do the experiment and I would have to of course change and do the experiment in a glove box. And so there was going to be a women’s change room and it just didn’t keep showing up. So I stood outside the men’s change room one day and said, “well, I guess I’m going to have to change in the men’s change room.” And the next day they had a women’s change room set up.

So, you know, it was just the usual drag that everybody had back in the time.

I was told by a secretary that there was one person who complained a lot and this was a former Manhattan Project person that I was working with my husband in the lab. And he was probably the one who put a little note in my personnel file that I was thought to be a communist agent. This was before there were safeguards put on what could go into personnel files.

Do you feel like the things with discrimination or even just attitudes, it sounds like you’re saying that the lab was not particularly an outlier one direction or the other. Do you feel that that’s fair?

Yeah, I think that’s fair enough.

There were some women at the lab and they were really good to me. When we had our orientation, when I just started at the lab, we went down to a reactor which is no longer there, but there was a woman operator at the reactor and of the group she said to me, here, you stand in front.

There was some solidarity among the women. And then there was another woman who was a physicist who made a point of saying, “hello, Cheryl,” to me. And I don’t know how she knew who I was. But it was a smaller lab and kind of everybody knew everybody. So I would not be surprised if she was aware that there was a new woman in the group of new employees.

Yeah, I think it was not an outlier in either direction. It was not great, but it was not the worst.

So you ended up working on lasers.

The laser division reorganized a lot. So I would continue in more or less the same job, but the designation of the group I was in would change.

And at some point, we split into a laser fusion division and a laser isotope separation division, which split the systems group pretty much down the middle. And I went to the laser isotope separation division, where I managed to get into experimental work.

What we were trying to do was molecular laser isotope separation using uranium hexafluouride (UF6), hitting it with lasers. There were some things we believed at first that turned out not to be true, like that you could excite UF6 molecules in some sort of selective way that would make them react in a particular way. Now it turns out that in a normal gas, you just have too much activity and the laser excitation goes away really quickly, much too quickly to produce a reaction. And so that was something that we struggled with. But one of the things I did was I got a really good ultraviolet spectrum of UF6, probably the best one that was available at that time. And I was working with my husband at this time in the lab. It was a start for me to actually be doing real science, and get publications and that kind of thing. And we did some cool things.

The lab was able at that time to do a lot of things that weren’t just narrowly focused on specific objectives. I wasn’t involved in the budget at this time, so I don’t know for sure it worked this way, but working backwards from what I know about budgeting of the lab, they must have gotten kind of a big chunk of money for the laser isotope separation program. And then I think there was a lot of latitude with how they could allocate that money. Just generally, there was a philosophy at the lab that doing additional work besides the particular objective was a good thing to do.

And that goes back to the Manhattan Project, too. Because from the Manhattan Project on they did a lot of chemistry, for example, of the actinides, because we didn’t know what it was. And you don’t know ahead of time how much of that will be relevant to what you’re doing and how much won’t. So doing more is better than doing less, because you might find something really cool. And there were times when they did.

We did an interesting little photochemical thing that had to do with nuclear reprocessing. And that is that in nuclear reprocessing, you have to reduce the plutonium from +4 to +3. And the way we did that was we reduced the uranium using ultraviolet light, and then the uranium reduced the plutonium. And we got a patent on that. Except that was about the time that the United States was deciding they weren’t going to do nuclear reprocessing. So, well.

It sounds like it was a relatively fluid environment, in terms of topics to work on.

I think there are changes now, but I’m not close enough to know about it. But the culture basically was you come in, and this was 1965, and you’re told, okay, you get a Q clearance, you are a staff member, and this was true even for me, a technical writer. And if we need to go back to some kind of program where we are working only on weapons, you will work only on weapons, this is the agreement that you are making with us. You have this job now, but that could change and you will change with it or leave. Which, you know, seemed like a fair deal to me because in 1965. We still had a pretty wild cold war going on.

So that was the agreement that you came into. But there was also an assumption that if you could get something going, that was a good thing too. And as I said, Bradbury in particular wanted to diversify the lab into peaceful research as well.

So there would be these programs and you could move easily from one to another. I think the funding was much more modular than it is now. And it was funding for this program and the lab gets to make a lot of the decisions on that program. By the time I left, that was no longer the case and Congress was deciding down to how much money my project would get. And so that has changed entirely.

But so the lab had this modular structure of programs, and you could move from one program to another. So my graduate training was in organic chemistry. But I wound up doing spectroscopy and building lasers and reaction kinetics and ultimately cleanups and plutonium chemistry. So there was a lot of room to do a lot of different things.

But the laser isotope separation program was probably one of the last of those really modular programs. And the lab was moving to more of a university structure where you have a professor and their postdocs and associated people. And it’s much smaller units. I don’t think it was a good thing.

How would you have felt if you were told you had to do weapons work? Did you give this thought?

Well, when I was was in the explosives group, that was obviously for weapons. I was only there for a couple of years. It didn’t particularly bother me, but I was just mainly doing documents and… it was OK with me.

I was lucky in getting into other kinds of programs as time went on. I eventually got a job in the Environmental Restoration Project, and I was managing cleanups of the land. And that connected me up with some people in Estonia who were cleaning up a former Soviet yellowcake plant.

And I enjoy doing projects where we get something done and find the answers to problems. We and the Estonians cleaned up a tailings pond that was a kilometer long and a half a kilometer wide right on the Baltic Sea. And I helped them do that. And I feel pretty good about that.

One last question: You were in your late teens when the Cuban Missile Crisis happened. What was that like?

I was in college, yes. I had mono. I was in the college infirmary and my roommate came over and told me what was happening and I thought, I don’t care if the world comes apart because I feel so miserable now, it would just be the right thing to happen. [laughing] But it was very frightening.

Enjoyable interview thank you..from Linda Marple , Cheryl’s sister❤️

>there was one person who complained a lot and this was a former Manhattan Project person that I was working with my husband in the lab. And he was probably the one who put a little note in my personnel file that I was thought to be a communist agent.

OK, I'll bite: We seem to be led to infer that those former MP people who stuck around the national labs postwar (and post O-hearing) maintained a tendency to red-bait (at least while they weren't busy walking on water in the eyes of their AEC/DoE successors)? Is that the intended inference to draw at least from those close to the action?