Hitting the jackpot

William Gibson's disturbingly plausible 21st-century slow disaster

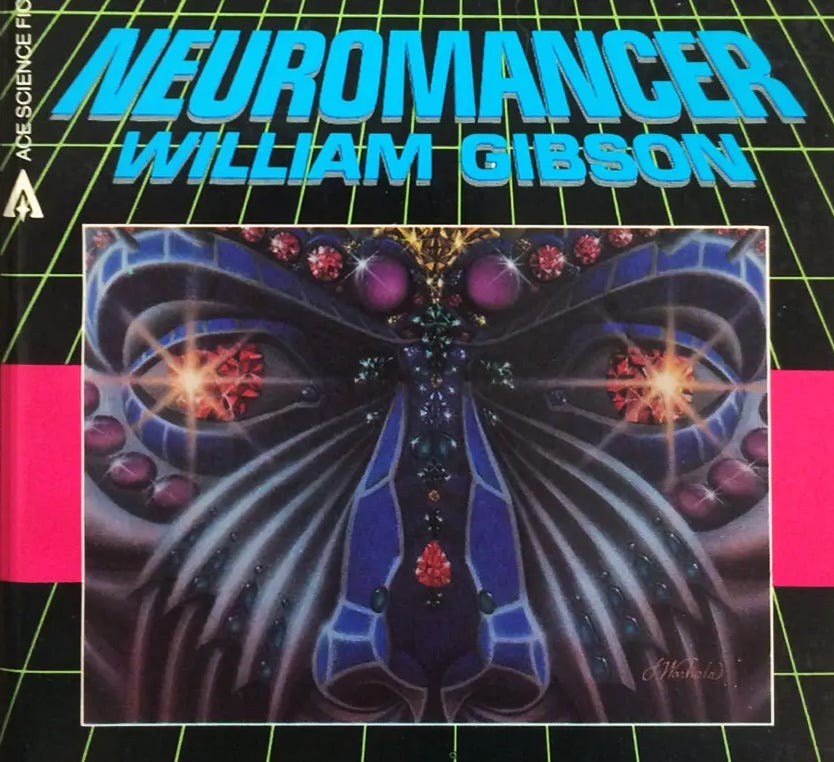

“Cyberpunk” has become so mainstream as an aesthetic, and so descriptive of our lived experiences, that it is hard to remember that it had to be invented. William Gibson’s mashing up of the high-tech and the gutter-punk, first in his stories in Burning Chrome (1982) and then in his opus Neuromancer (1984), dramatically deconstructed the prevailing notions of technological futures.

It’s not that Gibson’s work was uniquely dystopian, or the idea of “science fiction in a world full of dirt and decay” was so unheard of itself — the aesthetic of the original Star Wars is also a juxtaposition of the worn-out and the futuristic — but Gibson’s rendering of a future based around digital computation, urban sprawl and pollution, cybernetic humans, rogue artificial intelligences, and a political environment where faceless and shadowy corporate organizations matter more than nation states, still feels fresh.

What Gibson does so well, in his ice-cold prose, is the act of juxtaposition: it’s the intermingling of the high-tech and the low-world, globally distributed. It’s one generation’s marvels turning into the next generation’s normal, and eventually, their trash. It’s a world of in which the future and the past are intimately mingled, often glitchy, never quite as utopian as one might want to believe. It is an aesthetic that we see all around us, all the time, these days — intentional, and not.

(Above: Accidental cyberpunk in a Whole Foods parking lot, Edgewater, New Jersey.)

Most of Gibson’s books do not concern themselves with apocalypse, though. Neuromancer and the rest of his Sprawl trilogy — Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) — are set in a world that one might not want to live in, but they’re hardly worlds that have ended, either in a positive “End of History” sense (in which the world has settled into generally positive a post-political state) or a negative “End of the World” sense. The wheel of history continues to grind on in the Sprawl, for better and worse — it is not static.

Gibson has two other trilogies after the Sprawl (Bridge and Blue Ant), neither of which are apocalyptic, either. If anything, Gibson’s work could be said to get progressive less dire, the further away one gets from Neuromancer.

But his current trilogy, known as the Jackpot, of which only two books have yet come out (the next is vaguely hinted to come out later this year), is of a very different nature. The Peripheral (2014) the first in the series (and perhaps the best so far), takes place in two interconnected time periods: a possible future only a few decades from the present one, and another future set some seventy years beyond the first, whose agents are capable (I am being deliberately vague here) of communicating and interacting with the past. Let us call these “future A” and “future B” to distinguish them.1

The jackpot is what happens between “future A” and “future B.” It is simply called “the jackpot” (uncapitalized) in the book, and of course it is only people in “future B” who are aware of it. It is the disaster — Gibson’s apocalypse, of sorts.

So what is the jackpot?

The term, taken literally, is of course associated with winning, and gambling. It conjures to mind the wheels of a slot machine, each spinning, spinning, spinning, until, by some lucky whim of chance, they all independently align for the big, noisy, exciting payout.

Except, of course, if one tells you that “jackpot” is a negative, horrific thing, then the meaning shifts: what was once lucky becomes unlucky, and the loud clamor of lights, bells, shouting, and the clink of coins transform into something else — sirens and breaking glass, perhaps.

Gibson’s yet-unpublished third book may elaborate more on the nature of the jackpot in his fictional world — it is apparently going to be simply titled Jackpot — but the basic conceit of the idea as it appears in The Peripheral is that in between future A and future B, the world undergoes a dramatic change. It’s not a single event — no instant moment of horribleness, no monolithic threat, no singular moment of “payout.” It is, as a post-jackpot character describes it (via a plot device I am deliberately not-elaborating on) to a pre-jackpot character “it was no one thing”:

And first of all that it was no one thing. That it was multicausal, with no particular beginning and no end. More a climate than an event, so not the way apocalypse stories liked to have a big event, after which everybody ran around with guns […] or else were eaten alive by something caused by the big event. Not like that.

It was androgenic, he [post-jackpot] said, and she [pre-jackpot] knew from Ciencia Loca and National Geographic that that meant because of people. Not that they’d known what they were doing, had meant to make problems, but they’d caused it anyway. And in fact the actual climate, the weather, caused by there being too much carbon, had been the driver for a lot of other things. How that got worse and never better, and was just expected to, ongoing. Because people in the past, clueless as to how that worked, had fucked it all up, then not been able to get it together to do anything about it, even after they knew, and now it was too late.

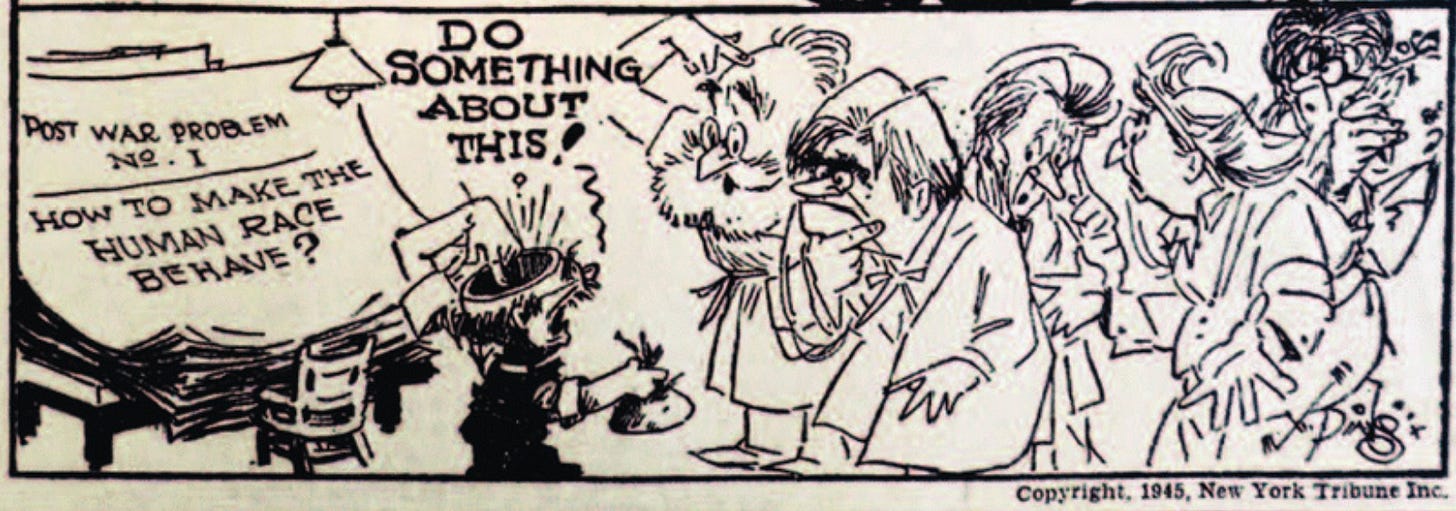

The jackpot is what scholars call a slow disaster. I really like how Scott Gabriel Knowles, a historian of disasters, talks about the concept slow disasters in this article of his from 2020:

The Anthropocene is also a disaster, but a slow one, moving according to a different temporal logic. The traditional definition of disaster describes an overwhelming event delimited by spatiotemporal limits that are tightly bounded with clear cause-and-effect relationships. “Slow disaster” is a way to think about disasters not as discrete events but as long-term processes linked across time.

The slow disaster stretches both back in time and forward across generations to indeterminate points, punctuated by moments we have traditionally conceptualized as “disaster,” but in fact claim much more life, health, and wealth across time than is generally calculated. The slow disaster is the time scale at which technological systems decay and posttraumatic stress grinds its victims; this is the scale at which deferred maintenance of infrastructure takes its steady toll, often in ways hard to sense or monetize until a disaster occurs in “event time.” The experience of war victims fits the concept well, as does the process of climate change, sea level rise, the intensification of coastal flooding, and heat waves.2

Slow disasters aren’t the ones that populate most disaster films or post-apocalyptic media. But the major catastrophe of our time — the Anthropocene generally, whatever this late-20th and early-21st century modernity is shaping into — is the slow disaster.

This isn’t to discount the possibilities of fast disasters. Nuclear war could still happen, along with a lot of other things that would produce disastrous effects over the course of days or hours. But what the idea of the slow disaster is getting at is that we should see many things that we tend to chalk up to just be “social or environmental problems” as being similarly devastating, just on a stretched-out timescale. This is, incidentally, how serious historians today think about some of the “major disasters” of the far past — the “fall of the Roman Empire,” inasmuch as historians are willing to talk about it as a “fall” at all (it’s a long story), was a slow disaster, a multi-causal transformation spread out over centuries, not just one night of Visigoths and fire in Rome.

So what does Gibson have in mind for specifics of the jackpot? He leaves it deliberately, and I think appropriately, vague:

No comets crashing, nothing you could really call a nuclear war. Just everything else, tangled in the changing climate: droughts, water shortages, crop failures, honeybees gone like they almost were now [in future A], collapse of other keystone species, every last alpha predator gone, antibiotics doing even less than they already did, diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves. And all of it around people: how people were, how many of them there were, how they’d changed things just by being there.

This is evocative and disturbing, more so than attributing it to any one cause. If you are being threatened by a singular force, you can imagine a singular response. If you’re being threatened by a non-linear world whose complexity has outstripped its capacity to handle it, who has for centuries taken for granted that its resources were infinitely exploitable when they were in fact plainly not, and a civilization that has created political and economic entities that are capable of destroying the world but not saving it… there’s no obvious solution there.

The character in future A who is hearing about Jackpot isn’t really surprised by it:

So now, in her day [future A], he said, they were headed into androgenic, systemic, multiplex, seriously bad shit, like she sort of already knew, figured everybody did, except for people who still said it wasn’t happening, and those people were mostly expecting the Second Coming anyway.

And we’re not surprised by it either, really, are we? This is all the stuff that informed people today simultaneously worry about and ignore to varying degrees.

And how do we ignore it? Sometimes by just focusing on our day-to-day (what else can we do?), sometimes by hoping that somewhere, somehow, a fix will be found. The most common fix, of course, is the technological one — maybe we’ll discover something that makes these problems just go away. Gibson’s Jackpot has an interesting take on that, too:

But science, he said, had been the wild card, the twist. With everything stumbling deeper into a ditch of shit, history itself become a slaughterhouse, science had started popping. Not all at once, no one big heroic thing, but there were cleaner, cheaper energy sources, more effective ways to get carbon out of the air, new drugs that did what antibiotics had done before, nanotechnology that was more than just car paint that healed itself or camo crawling on a ball cap. Ways to print food that required much less in the way of actual food to begin with. So everything, however deeply fucked in general, was lit increasingly by the new, by things that made people blink and sit up, but then the rest of it would just go on, deeper into the ditch. A progress accompanied by constant violence, he said, by sufferings unimaginable.

The culmination of the jackpot, which unfolds over five decades or so, is a dramatically depopulated world: 80% of the human population dies off. Apocalyptic by any definition. And yet, those 20% of survivors live in a technologically-impressive, wealth-abundant future.

This is both necessary for the plot of the book (how else does “future B” have the technology to communicate and meddle with “future A”), but it also is a very direct argument for the idea that even if scientific and technological progress keeps going on, it will be insufficient in the face of such broad system collapse.

It is both a perversion of the faith in techno-salvation while also, in its own way, an embrace of it. And it is not without historical precedent: how many narratives about the Black Death are about how the transformed world afterwards ended up ultimately being much the better? What is not our narrative about World War II than one about how despite the horror and atrocity and tragedy, the survivors ended up being healthier, wealthier, and vastly more powerful? It is reminiscent of how economists sometimes talk about vast social disruptions, like those brought about by automation: yes, it’s pretty bad for you now, but don’t worry, on the aggregate, in the future, everyone will be much happier on average.

But Gibson’s post-jackpot is no utopia; the jackpot had lasting consequences to how people organized themselves. Human society was part of the cause of the jackpot, and it didn’t come out of it necessarily having learned the “right” lessons:

None of that, he said, had necessarily been as bad for very rich people. The richest had gotten richer, there being fewer to own whatever there was. Constant crisis had provided constant opportunity. That was where his world had come from, he said. At the deepest point of everything going to shit, population radically reduced, the survivors saw less carbon being dumped into the system, with what was still being produced eaten by these towers they’d built […]. And seeing that, for them, the survivors, was like seeing the bullet dodged.

“The bullet was the eighty percent, who died?”

And he just nodded […] and went on, about how London, long since the natural home of everyone who owned the world but didn’t live in China, rose first, never entirely having fallen. […]

“Who runs it, then?”

“Oligarchs, corporations, neomonarchists. Hereditary monarchies provided conveniently familiar armatures. Essentially feudal, according to its critics. Such as they are.”

In other words, as the world came apart, liberal democracy utterly failed. What rose in its place was “the klept,” oligarchical forces who were able, through graft and violence, to seize power in chaos. Where Gibson’s Sprawl books imagine centralized cyberpunk dystopian power as being along the pattern of Japanese zaibatsus, with a tinge of yakuza, “the klept” seems modeled on Putin’s Russia, and the model they have, with some success, managed to export Westward.

It must be said that Gibson’s work is definitely not an attempt to predict the future. It is self-consciously a commentary on our early 21st-century anxieties. What makes Gibson good at this is that he’s capable of diagnosing anxieties that the bulk of us feel but often haven’t quite gotten around to articulate. I find it very telling that Neuromancer, a book that has been vastly influential in how we think about the darker potentials of a deeply-digital future, and at times feels prophetic, was written on a mechanical typewriter, by someone who did not own a computer. As he later wrote:

Neuromancer and its two sequels are not about computers. They may pretend, at times, and often rather badly, to be about computers, but really they’re about technology in some broader sense. Personally, I suspect they’re actually about Industrial Culture; about what we do with machines, what machines do with us, and how wholly unconscious (and usually unlegislated) this process has been, is, and will be. Had I actually known a great deal (by 1981 standards) about real computing, I doubt very much I would (or could) have written Neuromancer.

Similarly, the Jackpot books (so far) are not really about climate change, or a deeply-nuanced argument about the correlations between corruption, authoritarianism, and generalized collapse. It’s a book about that anxious, nagging feeling that many of us have had for the last decade and a half (or so) that perhaps the best days are not ahead for us as a civilization, but that the end of the world won’t be some obvious event, but a slow decline. Of a thousand little tragedies, all seemingly disconnected from any singular force, but linked by a shared context.

The fast disasters are terrifying enough, but one can imagine tackling them. Avoiding nuclear war, even in these dark days for arms control, still seems to me like an infinitely easier problem than solving the overlapping challenges of our unfolding slow disasters. Only a handful of states have nuclear weapons. They are governed, at least nationally, by laws. They are highly centralized, difficult to produce, and can be monitored from afar. They’re just machines, in the end, that can be taken apart. And there is some logic, however unreliable, mitigating against their use. All of these things make them much easier problems to tackle than climate change, poverty, ecological collapse, the rise of an oligarchical class, and so on.

So where does that leave us? Gibson’s Jackpot books, so far, are not unrelentingly dark at all. They contain within their plots the possibility for change, for course correction. Neither futures (A or B) are truly written in stone.

Knowles’ article on slow disasters concludes:

Or is there another option [beyond Anthropogenic collapse]? I don’t think any of us would be willing to work on slow disaster and Anthropocene research if we didn’t actually, maybe quietly, hold onto the idea that a course correction is possible, that a path away from the apocalypse is at hand, that we don’t have to die in the Anthropocene after all, that the field notes of the Anthropocenic DMZ excavation may indeed someday be collected by a person visiting a wildlife refuge.

To imagine such a thing, Knowles argues, it will at a minimum require us to think about these disasters correctly. If we only prepare for fast disasters, and do not understanding how systemic problems evolve into grand-if-slow disasters, then we will be lost. This is, I think, the social value of Gibson’s jackpot: not a prediction, but a warning.

There is an Amazon Prime adaptation of The Peripheral which is fairly close to the original source material in the first episode or so and then dramatically diverges from it in ways I think only did damage to its narrative intent. I do not recommend it. Among its many sins is trying to codify exactly what happened during the jackpot, and the end result is to trivialize it considerably. Other than this footnote I am going to pretend as if it does not exist.

Scott Gabriel Knowles, “Slow Disaster in the Anthropocene: A Historian Witnesses Climate Change on the Korean Peninsula,” Daedalus 149, no. 4 (2020): 192–206. DOI 10.1162/daed_a_01827

Good meditation on Gibson's idea. I've been thinking of it frequently as a version of the polycrisis gone much worse.

Incidentally, Gibson got the idea from Robert A. Heinlein, "The Year of the Jackpot," way back in 1952.

Nice to see the subject of collapse being discussed here.

I think a sober look at climate, energetic, economic, and political trends from a systemic pov shows a clear inexorable direction. Most of the difficulty for people seems to be the ability to take that sober look and clear assessment of the situation to make a rational analysis.

I hope to see more of this type of content being discussed here and will definitely check out the books!