At the heart of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) is the idea of the “Doomsday Machine.”

President MUFFLEY: The doomsday machine? What is that?

Ambassador DESADESKI: A device which will destroy all human and animal life on earth. […] When it is detonated, it will produce enough lethal radioactive fallout so that within ten months, the surface of the earth will be as dead as the moon!

General TURGIDSON: Ah, come on DeSadeski, that’s ridiculous. Our studies show that even the worst fallout is down to a safe level after two weeks.

DESADESKI: You’ve obviously never heard of cobalt thorium G.

TURGIDSON: No, what about it?

DESADESKI: Cobalt thorium G has a radioactive half-life of ninety three years. If you take, say, fifty H-bombs in the hundred megaton range and jacket them with cobalt thorium G, when they are exploded they will produce a doomsday shroud. A lethal cloud of radioactivity which will encircle the earth for ninety three years! […]

MUFFLEY: I’m afraid I don’t understand something, Alexiy. Is the Premier threatening to explode this if our planes carry out their attack?

DESADESKI: No sir. It is not a thing a sane man would do. The doomsday machine is designed to to trigger itself automatically.

One can think of the Doomsday Machine of Dr. Strangelove as having several separate associations:

It is obviously meant to be a metaphor for nuclear deterrence and the nuclear arms race in general. It is a weapon that makes sense according to a certain logic of strategy, but whose implementation ends up being an act of suicide.

It is a specific weapons concept (a “salted” or “Cobalt” bomb) that could have radioactive effects far beyond those of “normal” thermonuclear weapons.

It is a representation of a general idea of a machine that could destroy the entire world.

What I want to do is look at the history of each of these aspects of it, and how we get this idea into something like Strangelove as a central, motivating idea.

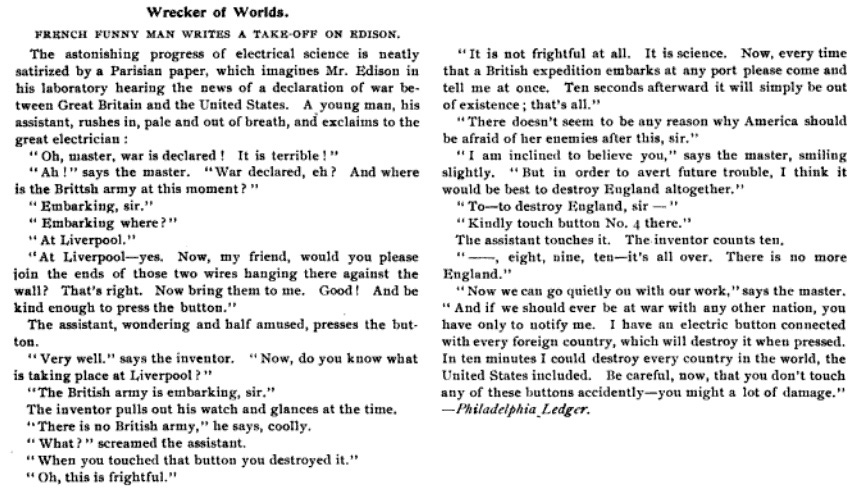

The latter association is perhaps the easiest to start with: a modern, technological machine that can easily destroy the world. The earliest instance of this trope that I have tracked down — which I am not suggesting is the first version of it, but gives a sense of its age — is from the 19th century. In 1896, a Parisian newspaper published a “skit” about how the American inventor and master of electricity, Thomas Edison, had made a machine that could destroy “every country in the world” at the push of a button. This was itself reprinted in the United States under the title, “Wrecker of Worlds.” “I have an electric button connected with every foreign country, which will destroy it when pressed,” the fictional Edison tells his assistant. “In ten minutes I could destroy every country in the world, the United States included. Be careful, now, that you don’t touch any of these buttons accidentally — you might do a lot of damage.”1

As the American translation of the article itself indicates, this “funny” story is a satire of “the astonishing progress of electrical science” in the late industrial revolution, and possibly anxieties about the rise of push-button automation in the “machine age.” It is not a serious idea for a machine, but this kind of “doomsday machine” represents an idea and an anxiety, embodied in fiction. It is not, in this short story, being used to make much of an argument, though — it presents this machine as something that would end the possibility of war with its owner (“If we should ever be at war with any other nation, you have only to notify me”) but does not explore the implications of that idea further.

Would not other nations immediately begin developing their own such machine, now that it had been revealed to the world? What happens if two nations have such machines? And so on. This is not a “Doomsday Machine,” to be sure — Edison is still very firmly at the controls, it is not automatic.

Let us now turn to the idea of a Cobalt bomb, or, more generically, a “salted” bomb. The idea here is relatively simple. Thermonuclear weapons would be a potent source of neutrons; one Los Alamos report from 1949 estimated that a “Super” bomb would produce something like 70 times more neutrons per gram of fuel than a fission bomb.2

Many otherwise inert elements, when exposed to neutrons, will absorb them and become radioactive versions of themselves. This phenomena of “artificial” or “induced” radioactivity was known prior to the discovery of nuclear fission, and the byproducts of such reactions vary dramatically in their radioactivity depending on what the new isotope created is.

Uranium-238 will, under bombardment by high-energy neutrons, undergo fission by itself, producing both energy and radioactive fission products.3 These are already pretty radioactive. But from at least mid-February 1950, and possibly as early as September 1947, the scientists at Los Alamos were aware of the idea of introducing materials that would become even more radioactive:

If... special arrangements are made to utilize the neutrons in making fission products or other radioactive materials, one gets effects similar to those in the case of the Alarm Clock. In fact, by absorbing the neutrons in appropriate materials and generating activities of the right kind, one might obtain from the Super many times the radioactive effect produced by an Alarm Clock.4

“Alarm Clock” here refers to a specific design for a thermonuclear weapon (or “Super”) which necessarily included uranium-238 in it, and thus a lot of fusion-induced fissioning; the above passage from a report by Edward Teller, they are pointing out that they could get far more “radioactive effect” than just the fission products produced by having uranium-238 in a “Super” bomb.

The popularizer of the idea was the famed Hungarian scientist Leo Szilard, who in February 1950 — only a few days after the above-mentioned report, curiously — took part in a roundtable discussion at the University of Chicago about the possibilities of the “Super” or hydrogen bomb. In it, he described a way in which the “Super” bomb could be made even more radioactive:

It is very easy to arrange an H-bomb, on purpose, so that it should produce very dangerous radioactivity. Most of the naturally occurring elements become radioactive when they absorb neutrons. All that you have to do is pick a suitable element and arrange it so the element captures other neutrons. Then you have a very dangerous situation. I have made a calculation in this connection. Let us assume that we make a radioactive element which will live for five years and that we just let it go into the air. During the following years it will gradually settle out and cover the whole earth with dust. I have asked myself: How many neutrons or how much heavy hydrogen do we have to detonate to kill everybody on earth by this particular method? I come up with about fifty tons of neutrons as being plenty to kill everybody, which means about five hundred tons of heavy hydrogen.5

He then elaborated the consequences of such a doomsday bomb:

What is the practical importance of this? Who would want to kill everybody on earth? But I think that it has some practical importance, because if either Russia or America prepare H-bombs — and it does not take a very large number to do this and rig it in this manner — you could say that both Russia and America can be invincible. Let us suppose that we have a war and let us suppose that we are on the point of winning the war against Russia, after a struggle which perhaps lasts ten years. The Russians and others can say: “You come no farther. You do not invade Europe, and you do not drop ordinary atom bombs on us, or else we will detonate our H-bombs and kill everybody.”

Faced with such a threat, I do not think that we could go forward. I think that Russia would be invincible. So, some practical importance is attached to this fantastic possibility. […] I do not know whether we would be willing to do it, and I do not know whether the Russians would be willing to do it. But I think that we may threaten to do it, and I think that the Russians might threaten to do it. And who will take the risk then not to take that threat seriously?6

Now we are getting very close to some of the dialogue in Dr. Strangelove, indeed. In April 1950, when the above was re-printed in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Szilard appended a footnote which specifically indicated that cobalt could be a useful element in such a scheme. Cobalt-59 (normal, abundant cobalt) can turn into cobalt-60 if it absorbs a neutron, and cobalt-60 has a half-life of about 5 years — short-enough to be dangerously radioactive, long-enough to not disperse over the course of a few weeks the way that fission products do.7

“Salted” bombs were studied by the US Atomic Energy Commission during the Cold War. There is some confusion in the literature on this, because they sometimes referred to “normal” thermonuclear weapons with U-238 components as “salted” weapons, as opposed to “clean” weapons which substituted U-238 for an inert element like lead. The term “salted” became preferred over “dirty,” because they didn’t like the association of talking about “dirty” bombs. Ultimately, nearly all of the US thermonuclear weapons deployed were in fact “dirty” in this way — in that at least half of their yield came from the fissioning of U-238.

The reports I have seen suggest that after further study, the US saw little military utility in “true” salted bombs, like Szilard’s cobalt bomb idea. Nuclear fallout of the “normal” sort (fission products) was bad-enough, and had the convenient property of becoming much less acutely radioactive on a timescale of weeks. A weapon whose fallout stayed deadly for months or years was not particularly useful if you were imagining that a nuclear war would not just be an “everybody dies” situation, but a situation where you might imagining being the “victor” in some way. A doomsday machine of the sort imagining by Szilard (or in Dr. Strangelove) is not something you’d want to have if you thought nuclear war was likely and you might be able to “win” it, in other words.

But the idea stuck around, particularly as a metaphor. Nevil Shute’s novel On the Beach (1957) describes the aftermath of a nuclear war in which cobalt bombs were used by the thousands, creating a doomsday cloud that circles the Earth, eradicating all life. The book on which Dr. Strangelove was based, Peter George’s Red Alert (1958), also describes a Doomsday Machine:

It is a quite simple idea, but if you look at it carefully you will see it really is the ultimate deterrent. You take a couple of dozen hydrogen devices. They don’t need to be bombs, no airplane is going to be called on to carry them. You jacket those devices in cobalt, and you bury them in a convenient mountain range. They can be exploded at the press of a button. All of them. How long would you give human life on this earth after such an explosion? […]

The Atomic Energy Commission were given that question as a theoretical exercise. Their answer was this. That all life would cease in the northern hemisphere between eight and fourteen weeks after the explosion. […] There would be no escape from the radio-active cloud. It would enshroud the entire earth, and poison every living organism. It would retain its lethality for hundreds of years. It would mean the end of the world. Literally.

Unlike in Dr. Strangelove, this monologue was given to those in the war room by the President himself — one of the many differences from Kubrick’s 1964 screenplay. There is no Strangelove character in the novel; the novel plays all of this quite straight, not as satire; and the Doomsday Machine is not automatic at all.

The jump to Strangelove for Doomsday Machines likely came from the work of game theorist think-tanker Herman Kahn, whose books Kubrick studied deeply when researching the film, and who is one of the (several) inspirations for the character of Dr. Strangelove. Kahn’s 1960 classic On Thermonuclear War contains an extensive discussion of the idea of a Doomsday Machine, and may be the one who first coined the term (he certainly popularized it).

Kahn distinguished between three types of “conceptualized devices,” the Doomsday Machine, the Doomsday-in-a-Hurry-Machine, and the Homicide Pact Machine. (One can criticize Kahn on many levels, but his skill in coming up with evocative names appears unmatched.) The Doomsday Machine of Kahn was defined as:

A Doomsday Weapon System might hypothetically be described as follows: let us assume that for 10 billion dollars one could build a device whose function is to destroy the earth. This device is protected from enemy action (perhaps by being situated thousands of feet underground) and then connected to a computer, in turn connected to thousands of sensory devices all over the United States. The computer would be programed so that if, say, five nuclear bombs exploded over the United States, the device would be triggered and the earth destroyed. 8

Kahn did not believe that either the US or the USSR would actually build such an automatic machine; it was an “unsatisfactory basis for a weapon system,” he argued, because its cost would be so high that it would invite scrutiny, “a scrutiny which would raise questions it could never survive.”

But as a concept, it was for Kahn useful way to think about what went into making a good deterrent. He listed six “desirable characteristics of a deterrent,” reproduced above, and pointed out that, in his estimation, a good Doomsday Machine could easily satisfy the first 5 characteristics. The one that most tricky was how controllable it was; because the Doomsday Machine was automatic, any failure of deterrence of a large-enough scale to trigger it would be catastrophic. “A failure kills too many people and kills them too automatically,” as he put it.9

The Doomsday-in-a-Hurry Machine would be very similar, but would involve a more fine-grained tuning to the kinds of “acts” that would trigger it. The Homicide Pact Machine is basically a form of automatic Mutual Assured Destruction, in which a mutual triggering would cause two nuclear nations to annihilate one another. Kahn notes:

The major advantage of the Homicide Pact is that one is not in the bizarre situation of being killed with his own equipment; while intellectuals may not so distinguish, the policy makers and practical men prefer being killed by the other side. It is just because this view no longer strikes some people as bizarre that it is so dangerous.10

Kubrick’s Doomsday Machine is Kahn’s Doomsday Machine in both name and function: it is an automatic suicide machine, one that takes the whole world down with it. Kubrick of course was using this as a metaphor for the arms race and deterrence in general. Kahn would no doubt object that the more apt metaphor is the Homicide Pact Machine, as that is essentially what the actual late arms race evolved into.

The United States never developed anything like a Doomsday Machine in the sense that either Kahn or Kubrick meant it. Of course, as Dan Ellsberg (among many others) argued, the Homicide Machine of the arms race was in no great way quite distinguishable from a Doomsday Machine. But it was not automatic; even the Soviets’ famous Perimetr/Dead Hand system was not quite as automatic as the actual Doomsday Machine (humans were still involved at every stage).

The issue is not its impossibility — all of these things from the cobalt bomb onward are possible. As Dr. Strangelove put it: “the technology required is easily within the means of even the smallest nuclear power. It requires only the will to do so.”

So why did the US not have the “will” to do it? I think Kahn does partially hit the nail on the head: people prefer committing mutual homicide to mutual suicide at some level, and it is too automatic. The war planners did want to deter global nuclear war, but they also wanted to be able to imagine winning nuclear war if it did happen. And a Doomsday Machine doesn’t let you do that kind of thing — it shatters the illusion that nuclear war can be won, just as it challenges the idea that we, the humans that made it, are really the ones in control of this technology.

I wrote a bit about this and the trope of “push-button war” some years back.

F. Reines and B.R. Suydam, “Preliminary Survey of Physical Effects Produced by a Super Bomb,” LAMS-993 (November 18, 1949).

Uranium-238 is fissionable but not fissile; it can be split by high-energy neutrons, but it will not continue the reaction, as the neutrons it releases are too low of an energy to induce further fissioning in uranium-238. This sort of graph, showing the probability of fissioning in different isotopes (vertical axis, logarithmic) as a function of neutron energy (horizontal axis, also logarithmic), with the energy levels of neutrons emitted by fission itself, illustrates the issue well, I think, if you take the time to study it.

E. Teller, “On the Development of Thermonuclear Bombs,” LA-643 (February 16, 1950), 25. The version of this report that I have seen is dated in February 1950, as indicated. There are other citations of it that place its date as September 26, 1947, and yet another of the same name and number dated May 7, 1948. The report itself seems to be a summary of things known by the summer of 1947. Whether the “salting” idea goes back as early as 1947, or was interpolated into the information once it was written up in 1950, I do not know. I am also not entirely clear why there are so many different cited dates; it is unusual.

“Facts about the Hydrogen Bomb,” University of Chicago Round Table 623 (February 26, 1950), 7.

Ibid., 8.

Hans Bethe, Harrison Brown, Frederick Seitz, and Leo Szilard, “Facts about the Hydrogen Bomb,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 6, no. 4 (April 1950), 106–126, on 109. See also David Lilienthal’s statement on page 109, in which he denounces the four as the “oracles of annihilation” trying to create a “new cult of doom”!

Herman Kahn, On Thermonuclear War (Princeton University Press, 1960), 145.

Ibid., 147.

Ibid., 152. In an earlier version of this work, Kahn called this a Suicide Pact Machine. One can see why he changed it, to make it more distinct from the suicidal Doomsday Machines. Herman Kahn, “The Arms Race and Some of Its Hazards,” Daedalus 89, no. 4 (Fall 1960), 774–780.

Thanks for this excellent article. Kubrick met Hermann Kahn several times and both he and his wife Christiane were shocked by how intelligent the man was, quite a compliment considering that most of the people that worked with the director considered him a genius. This is a quote from Christiane Kubrick from the excellent "Reconstructing Dr.Strangelove", written by my friend Mick Broderick, sadly recently passed away. "I thought (Kahn's) brain has obviously run away from him a long time ago. He could think so fast. And he must have been so isolated from the rest of the world. Can you imagine being that much more intelligent than everybody else? Which he was. And at first it struck me a little bit like Rain Man, you know. A savant. (..] He just was that much more intelligent than other people. He could think that much faster than other people because he could speak that much faster than other people, and had this all round total recall of absolutely everything - a memory, I mean, just a much bigger computer. And we would sit there astonished. How boring it must be for him, sitting with two golden retrievers and trying to explain mathematical truths to them! That's what we both felt like, you know... in fact I think he slowed down considerably for us just so he had company. But that's what we felt. Sort of sitting up and trying to understand desperately."

I always assumed that the Bulletin's "Doomsday” (as per the “Doomsday Clock") referred to the last great conflagration; and the real doomsday machine was (is ?) the sheer quantity (and yield) of Soviet and US cold-war warheads ... peaking in the range of 40,000 deliverable nukes. That being many more nukes than there are cities, worldwide, with populations over 25,000. That would certainly be an unrecoverable event and therefore globally existential: i.e., a full-scale US-USSR war in the 1960s.

“Doomsday” was in the layman’s mind, a rational idea (it didn’t need to be a sinister idea; i.e., “if we can’t have the world, nobody can, threat) considering the forces and destruction of collective and immediate-term deployment of so many nuclear weapons. There was no need for a “Deadhand” under those circumstances. MAD equals Doomsday, plain and simple.

At that time (at least in common public parlance), Doomsday was not understood to be caused by post-detonation radiation effects; it was caused by conflagration (explosions and firestorms). Unknown to the public at that time ( of the Cold War), the now declassified Groves-Nicols Memo reveals that radiation effects were legitimately considered lethal ballistic effects of nuclear materials, and more likely the easier weapon to develop than fission weapons. But at MED they surprised themselves and were able to produce fission and fusion warheads much faster than anticipated. The MED idea of radiation weapons required the impossible high-volume cyclotron production of tons of radionuclides to be spread into the air over enemy cities. It was not physically feasible and timely to attempt to produce the quantities required for any wide-scale use of such a horrendous weapon (which was kept out of the public discourse). Blowing up and burning people in a few minutes being much more endearing weapons’ effects than weapons' effects causing weeks of torturous death from ARS (acute radiation syndrome).

What was not recognized at the time, or perhaps not palatable in the senior ranks of the AEC (Atomic Energy Commission) as a legitimate scientific or respectable weapons’ effect was the fact that nuclear weapons were already highly lethal radiation weapons. Death from ARS was a lethal contingent of any nuclear war. This effect in Japan was kept a secret from the US public by DoD for years.

Tritium and U238 can do it all. The idea of “radiation bombs” was really quite silly. Radiation is a physical and military reality of nuclear weapons. To make it into a new and optional ballistic effect was largely Cold War propaganda. I remember the public discourse at the time: it’s as if there is a choice to eliminate ionizing radiation and neutron-activation created fallout from the Bomb.

All nuclear fission bombs detonated adjacent to any mass, generate lethal radioactive fallout by neutron activation.

Lethal radioactive fallout is a function of optimized height-of-burst detonations, explosion geometry, and target interaction. Pulverize and entrain as much mass as possible. It’s that simple. The ingredients for fission boosting (U238, tritium) are already in the “conventional nuke” (couldn’t resist the oxymoron).

Nuclear war’s Doomsday was already the lethal radiation fallout causing death of enemy civilians for months after deployment and rendering their homelands uninhabitable, toxic wastelands. We didn’t need some silly salted-bomb construct to purge the original bomb of its radiation ballistics and try to bring righteousness into using radiation (tortuous slow death) as a legitimate military tactic.

By highlighting and redirecting attention from the horror of the inherent radiation effects of our bombs, by telling us radiation could be controlled, we would be less afraid of it. Perhaps more supportive of using it on others. And it wasn’t us, it was the Soviet Doomsday Machine (Deadhand) we had to fear. Playing into the narrative of public opinion management using a well-engineered anxiety and tension, so we don’t resist the nuclear program (military and domestic) because we can control it for war and peace.

Meanwhile, the third and most likely cause of Doomsday was left out of the conversation at that time: nuclear war precipitated climate change (i.e., Nuclear Winter).