"Nuclear weapons repel all thought, perhaps because they can end all thought"

Martin Amis on the difficulties of writing about nuclear war

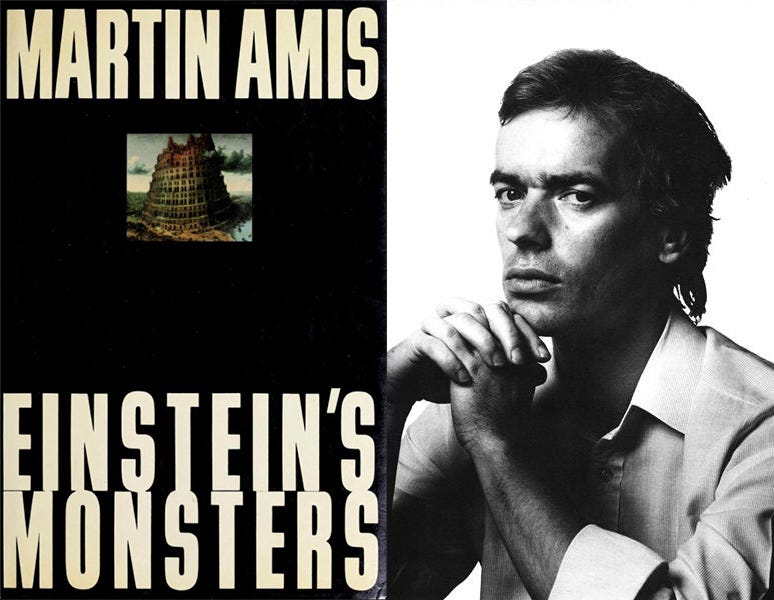

Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters (1987) is a collection of five short stories that are, to one degree or another, are meant to be reflective of the nuclear age. Amis clarifies in an author’s note that the title refers to nuclear weapons, “but also to ourselves”: “We are Einstein’s monsters, not fully human, not for now.”

The stories themselves are their own things to be reckoned with — we’ll come back to them another time — but his introductory essay, titled “Thinkability,” is a fascinating polemic with which to introduce a collection of fiction. It is perhaps one of the most evocative and writerly polemics on nuclear weapons from the 1980s that I know of. One doesn’t have to agree with every argument Amis makes to be impressed at how he makes them, and to feel the urgency in his voice:

Now, in 1987, thirty-eight years later [from his birth in 1949], I still don’t know what to do about nuclear weapons. And neither does anybody else. If there are people who know, then I have not read them. The extreme alternatives are nuclear war and nuclear disarmament. Nuclear war is hard to imagine; but so is nuclear disarmament. (Nuclear war is certainly the more readily available.) One doesn’t really see nuclear disarmament, does one? Some of the blueprints for eventual abolition […] are wonderfully elegant and seductive; but these authors are envisioning a political world that is as subtle, as mature, and (above all) as concerted as their own solitary deliberations. Nuclear war is seven minutes away, and might be over in an afternoon. How far away is nuclear disarmament? We are waiting. And the weapons are waiting.

Amis is a master of the “kicker,” that final sentence of a paragraph that, if properly executed, kicks you right in the gut. I can say from experience that a good kicker is hard to write. Amis may, it could be argued, go a bit too far in ladening this essay with kickers — if every paragraph has a kicker, it dulls the effect over time. But it makes for some sharp quotes.

The ultimate thrust of the piece is about the difficulty about writing well about nuclear weapons. How does one write about a sword hanging above one’s head?

Soon after I realized I was writing about nuclear weapons […] I further realized that in a sense I had been writing about them all along. Our time is different. All times are different, but our time is different. A new fall, an infinite fall, underlies the usual—indeed traditional—presentiments of decline. […]

The “effects” of nuclear weapons have been exhaustively studied, though of course nobody will ever know their full extent. What are the psychological effects of nuclear weapons? As yet undetonated, the world’s arsenals are already waging psychological warfare; deterrence itself, for instance, is entirely psychological (and, for that reason, entirely inexact). The airbursts, the preemptive strikes, the massive retaliations, the uncontrollable escalations: it is already happening inside our heads. If you think about nuclear weapons, you feel sick. If you don’t think about them, you feel sick without knowing why. Nuclear weapons repel all thought, perhaps because they can end all thought. […]

Clearly a literary theme cannot be selected, cannot be willed; it must come along at its own pace. Younger writers, writers who have lived their lives on the other side of the firebreak, are beginning to write about nuclear weapons. My impression is that the subject resists frontal assault. For myself, I feel it as a background, a background which then insidiously foregrounds itself. Maybe the next generation will go further; maybe the next generation will be more at home with the end of the world. . . . Besides, it could be argued that all writing—all art, in all times—has a bearing on nuclear weapons, in two important respects. Art celebrates life and not the other thing, not the opposite of life. And art raises the stakes, increasing the store of what might be lost.

This is interesting stuff; this is a writer trying to engage with his context, and his context is thought-destroying. The 1980s were, in Western Europe and the United States, the peak of nuclear anxiety and nuclear fear, at least as reflected in public opinion surveys, mass mobilization, and fearful media (WarGames, The Day After, Threads, etc.). If you were going to be worried about nuclear war, the 1980s were the place to be — even the 1950s and 1960s tend not to rank as high in terms of public fear, at least according to the public opinion polling that is available.1

In the essay, Amis directly credits Jonathan Schell’s Fate of the Earth (1982) as the “classic, awakening study” that got him consciously interested in nuclear weapons: “It woke me up. Until then, it seems, I had been out cold. I hadn’t really thought about nuclear weapons. I had just been tasting them. Now at last I knew what was making me feel so sick.”

He elaborates further:

I first became interested in nuclear weapons during the summer of 1984. Well, I say I “became” interested, but really I was interested all along. Everyone is interested in nuclear weapons, even those people who affirm and actually believe that they never give the question a moment’s thought. We are all interested parties. Is it possible never to think about nuclear weapons? If you give no thought to nuclear weapons, if you give no thought to the most momentous development in the history of the species, then what are you giving them? In that case the process, the seepage, is perhaps preconceptual, physiological, glandular. The man with the cocked gun in his mouth may boast that he never thinks about the cocked gun. But he tastes it, all the time.

There is something literally visceral here: nuclear weapons make you feel sick, they are something you can taste, they are a source of revulsion and physical horror. He repeats this theme of bodily sickness again and again:

I am sick of them—I am sick of nuclear weapons. And so is everybody else. When, in my dealings with this strange subject, I have read too much or thought too long—I experience nausea, clinical nausea.

This bodily fascination was Amis’ antidote, perhaps, to the problems he saw of nuclear writing. When discussing the works of so many other writers, he laments that they are either clinical to the point of abstraction, engaged in bizarre fantasies, or, even worse, trying to address it with bad attempts at humor. He finds E.P. Thomson’s attempts to use rough satire to argue against nuclear weapons (“Hallo! Mr. Reagan, is zat you? Tovarich Brezhnev here. Come on out with your hands up, or I put zis Bomb through the window!”) an utter defeat:

Everything in you recoils from this. You sit back and rub your eyes, wondering how much damage it has done. For in the nuclear debate, as in no other, the penalty for such lapses is incalculable.

Scorched earth, indeed. Amis regards Civil Defense as “another satirical voice,” one that is (unlike Thomson) actually funny. He is firmly in the camp of those who believe survival after a nuclear attack is pointless:

There are only two words to be said, and they are forget it. […] Dispel any interest in surviving, in lasting. Have no part of it. Be ready to turn in your hand. For myself and my loved ones, I want the heat, which comes at the speed of light. I don’t want to have to hang about for the blast, which idles along at the speed of sound. There is only one defense against nuclear attack, and that is a cyanide pill.

This is one of those passages that I can’t bring myself to completely agree with, but I nonetheless an impressed by its rhetorical power.

In another passage, Amis uses repetition to hammer home the circular nature of nuclear deterrence:

What is the only provocation that could bring about the use of nuclear weapons? Nuclear weapons. What is the priority target for nuclear weapons? Nuclear weapons. What is the only established defense against nuclear weapons? Nuclear weapons. How do we prevent the use of nuclear weapons? By threatening to use nuclear weapons. And we can’t get rid of nuclear weapons, because of nuclear weapons. The intransigence, it seems, is a function of the weapons themselves. Nuclear weapons can kill a human being a dozen times over in a dozen different ways; and, before death—like certain spiders, like the headlights of cars—they seem to paralyze.

The weapons paralyze, the overwhelm, they hollow out. Amis hangs on nuclear weapons the moral failings of our times:

How do things go when morality bottoms out at the top? Our leaders maintain the means to perform the unthinkable. They contemplate the unthinkable, on our behalf. We hope, modestly enough, to get through life without being murdered; rather more confidently, we hope to get through life without murdering anybody ourselves. Nuclear weapons take such matters out of our hands: we may die, and die with butcher’s aprons around our waists. I believe that many of the deformations and perversities of the modern setting are related to—and are certainly dwarfed by—this massive preemption. Our moral contracts are inevitably weakened, and in unpredictable ways. After all, what acte gratuit, what vulgar outrage or moronic barbarity can compare with the black dream of nuclear exchange?

At times, he despairs, frustrated by a lack of ability to do anything about the situation: “What am I to do with thoughts like these? What is anyone to do with thoughts like these?” Even ignoring it is not an option for Amis, not really; aside from whatever civic duty might exist to worry about it, it is always there, in the backdrop, just outside of vision.

And even if deterrence is successful, what kind of success is it?

The A-bomb is a Z-bomb, and the arms race is a race between nuclear weapons and ourselves. It is them or us. What do nukes do? What are they for? Since when did we all want to kill each other? Nuclear weapons deter a nuclear holocaust by threatening a nuclear holocaust, and if things go wrong then that is what you get: a nuclear holocaust. If things don’t go wrong, and continue not going wrong for the next millennium of millennia (the boasted forty years being no more than forty winks in cosmic time), you get . . . What do you get? What are we getting?

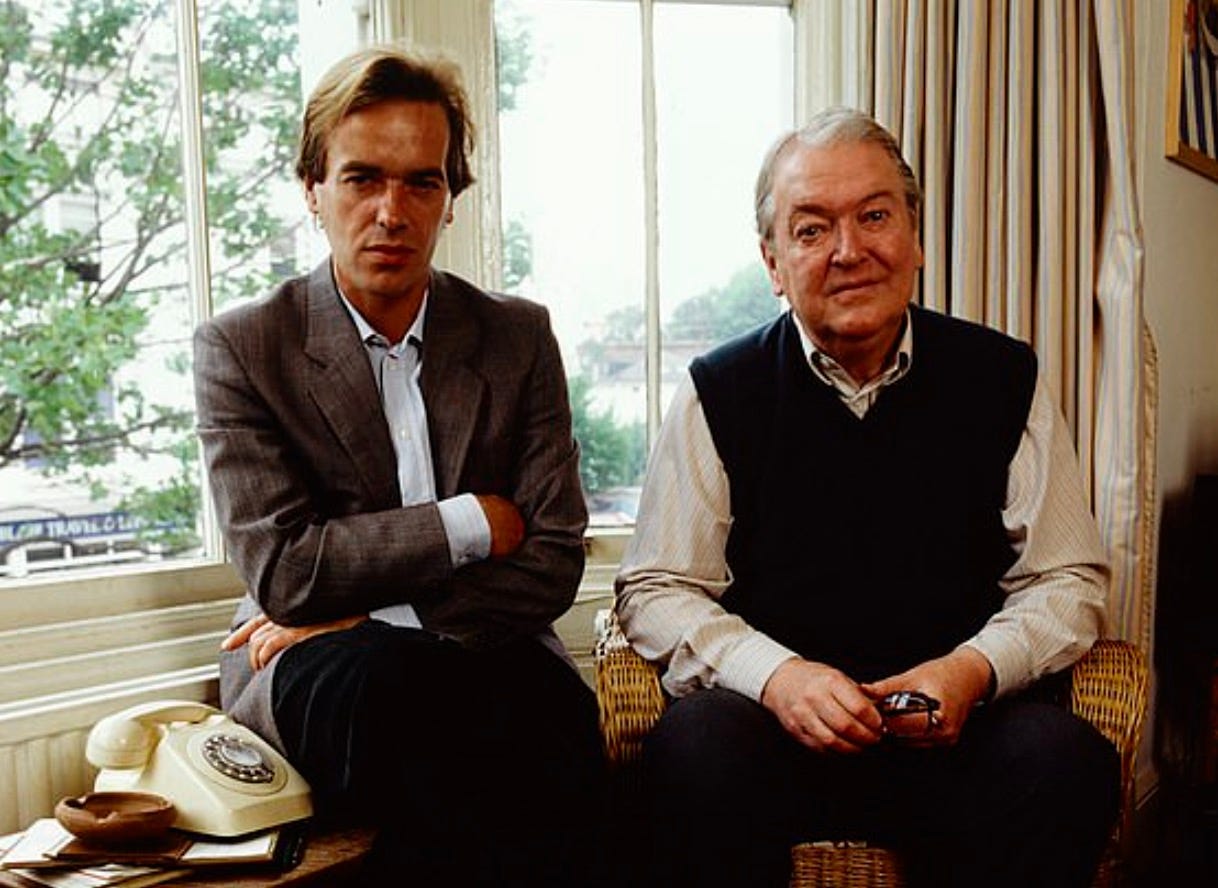

In his essay, Amis says that he and his famous father, Kingsley Amis, did not see eye to eye on the matter, and that this divide is, he thinks, purely generational: “I argue with my father about nuclear weapons. In this debate, we are all arguing with our fathers. […] They got it hugely wrong.”

But in his 2000 memoir, Experience, Amis went into considerable depth about his father’s specific reaction after Einstein’s Monsters was published:2

Having read the Letters, I now know that Kingsley was genuinely — and, it seems to me, hilariously — infuriated by my taking up this position. […] At the end of the week that saw the publication of Einstein’s Monsters I took my three-year-old boy, as usual, to Sunday lunch at my father’s house; and Louis, I remember, was aghast at our opening exchange:

— I READ YOUR THING ON NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND IT’S GOT ABSOLUTELY BUGGER-ALL TO SAY ABOUT WHAT WE’RE SUPPOSED TO DO ABOUT THEM.

— WELL IT’S NOT SURPRISING IS IT BECAUSE AFTER FORTY YEARS NO ONE ELSE KNOWS WHAT TO DO ABOUT THEM EITHER.

Come to think of it, he did look genuinely infuriated: as hostile as I ever saw him. My brother Philip does a flawless imitation of Kingsley in this state: the whole head vibrating, the eyes dangerously swollen, the tensed mouth in a violent false smile, and (most tellingly) the nails of the forefingers scrabbling, almost bloodily, at the cuticles of the thumbs …

One can imagine that Amis might have seen his father’s anger as, perhaps, as visceral a reaction as the nausea, paralysis, frustration, and general disgust that he himself reported feeling when he contemplated the vast killing machine that was the global nuclear arsenal.

See e.g. Tom W. Smith, “A Report: Nuclear Anxiety,” Public Opinion Quarterly 52, No. 4 (Winter 1988), 557-575, which collates many different surveys. The author suggests that “fear probably peaked during the Cuban Missile Crisis,” but notes a dearth of data to that effect.

Martin Amis, Experience (Knopf, 2000), 59.

Great ideas and well written analysis of the social and infrastructure issues regarding nuclear war. However, his knowledge of nuclear physics shows some old stereotypes and assumptions which demonstrate a lack of recent study of the weapons themselves. The number of options and flexibility has not made them less frightening, but has changed the playing field a lot.

... enjoyed this!