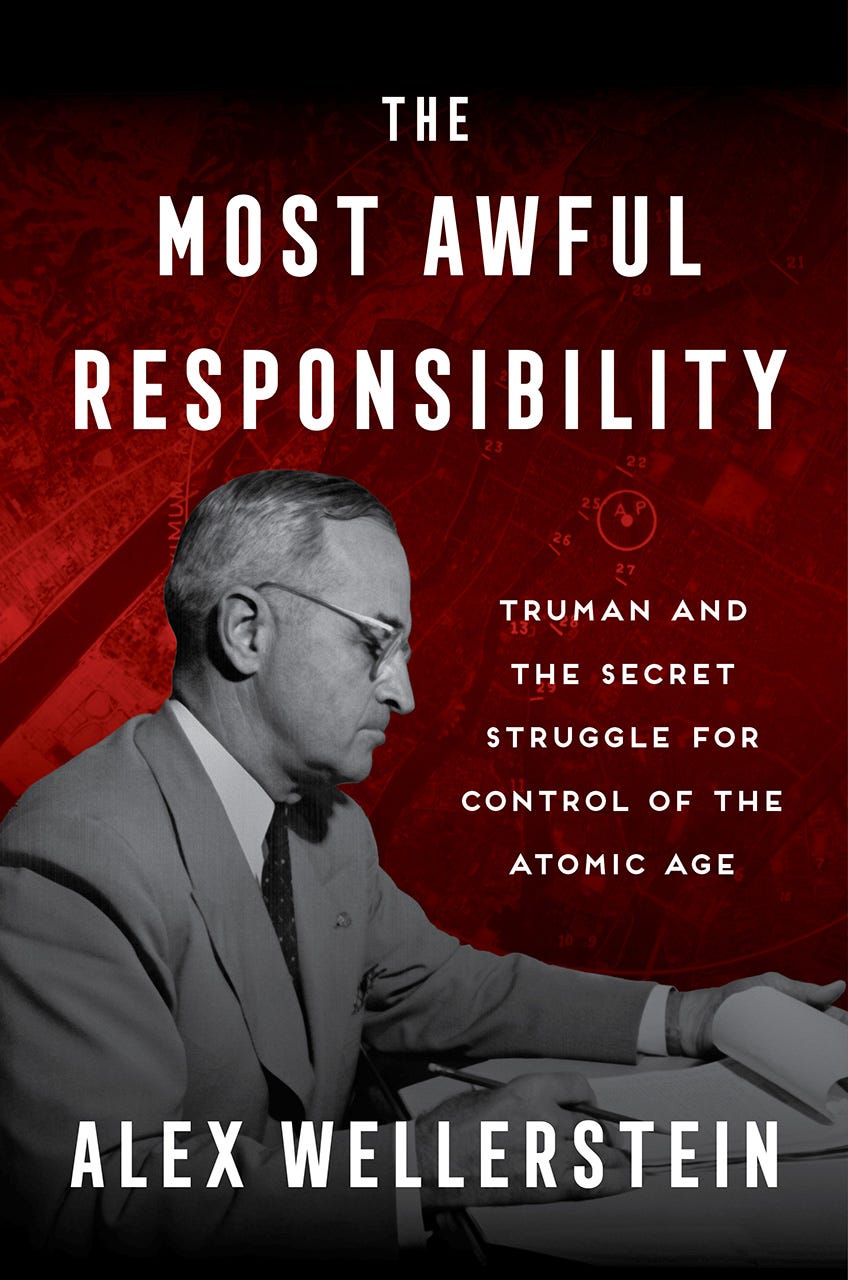

"The Most Awful Responsibility"

My new book on Truman and the bomb will be released on December 9!

On December 9, 2025, my newest book will go on sale from HarperCollins: The Most Awful Responsibility: Truman and the Secret Struggle for Control of the Atomic Age. I thought it would be worth writing up a bit, in my own words, about what this book was about.

My new book is an “atomic biography” of President Harry Truman, covering primarily the years he was in office (1945-1953).

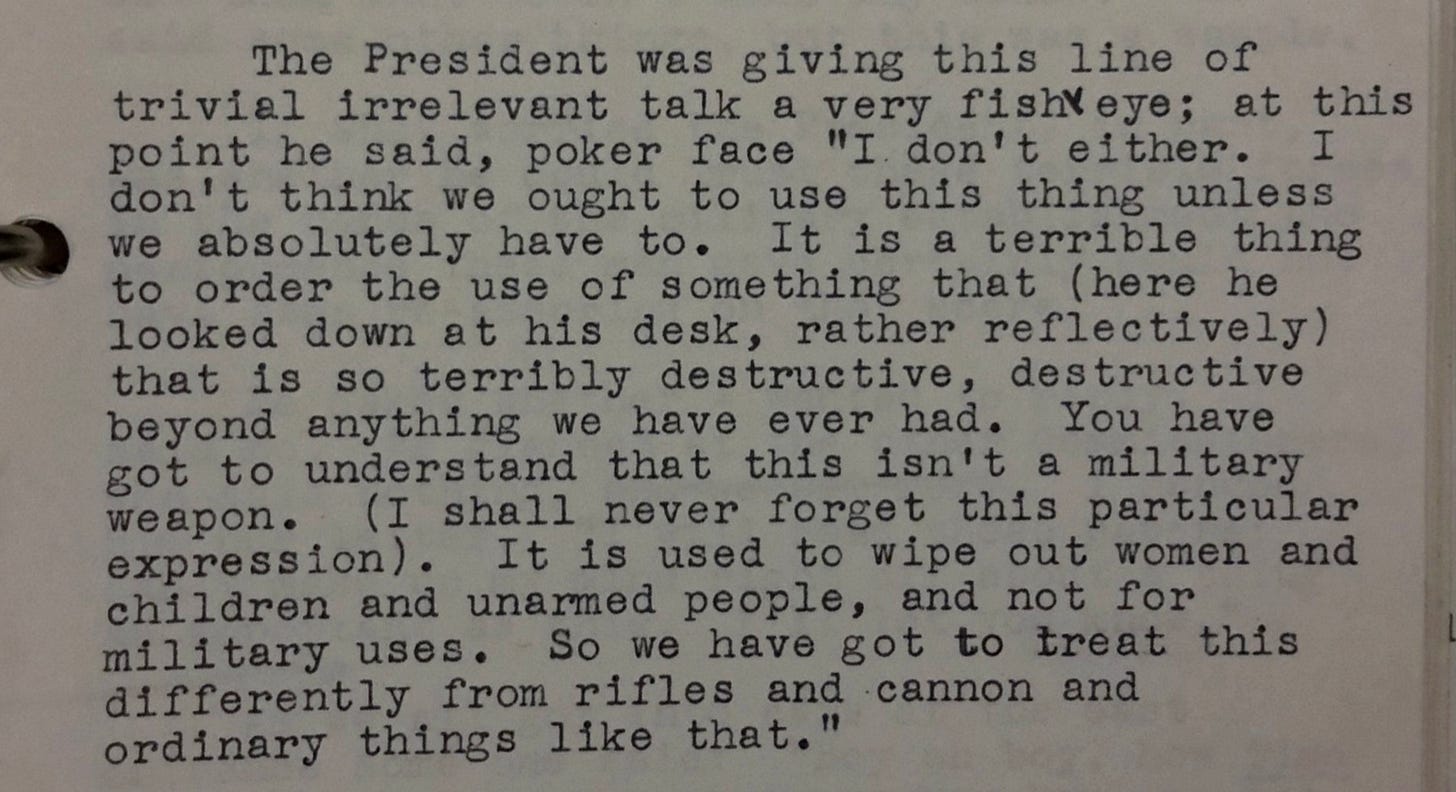

My essential argument is that Truman was far more anti-nuclear than he gets credit for. He was deeply horrified by the idea of using atomic weapons, which he associated with the “slaughter” and “murder” of “women and children” (all his words).

This deep moral animosity went well beyond the sentiments of nearly all of his advisors, the military, government administrators, and even the general attitudes of the American public. These were personal, idiosyncratic, and deeply-held views. And because Truman happened to be the president at this moment, and because he worked very hard after World War II to establish the president as a key figure in atomic policymaking, these views had a profound impact on the development of American nuclear weapons policies during the crucial early period of American nuclear monopoly and the early Cold War.

Now, I recognize that this argument will likely suggest a few obvious paradoxes to you. The reason that Truman is not associated with anti-atomic sentiment is because he presided over the only uses of nuclear weapons against cities in war. He also presided over the development of the hydrogen bomb and an expansion of the US nuclear arsenal that began in the final years of his presidency but would reach gargantuan heights by the end Eisenhower’s presidency. If what I say about his attitudes and their impact is true, how does one square that with these contradictory indication?

In the book, I go over each aspect of early American atomic policy, from the atomic bombings through the non-use of the atomic bomb in the Korean War, closely and with fresh eyes, reexamining every primary source I could get my hands on anew, as well as some new sources previously unavailable or unexamined by scholars. What I have found significantly varies from not only what most people understand this history to be, but what most scholars do as well.

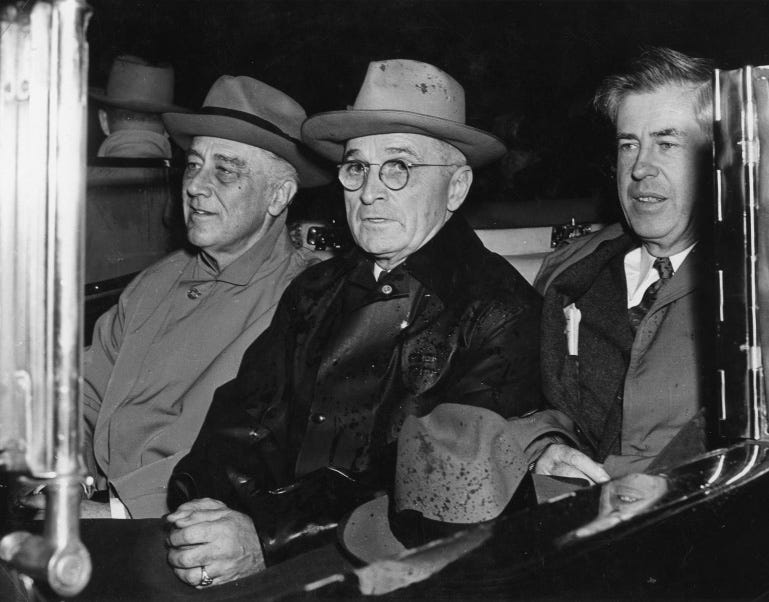

The first third of the book discusses the lead up and immediate aftermath of the use of the bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Unlike most accounts, I try to laser in on exactly what Truman did and did not know about the bomb and the plans to use it. For several decades now, scholars have understood that Truman was far from the “decider” on the bomb that he has been depicted as being — that he even depicted himself as being. His role, as General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, and one of the people who was actually doing most of the operational planning on the atomic bombs, put it, was essentially of “one of noninterference — basically, a decision not to upset the existing plans.”

I have found that it goes a bit further than this. My thesis is that Truman did not actually understand “the existing plans” very well, and that what believed them to be was quite different from what they actually were.

In particular, I have concluded, again from a close reading of the contemporary sources, is that it is more likely than not that:

Truman believed that Hiroshima was “purely” a military base, and not a city full of “women and children”;

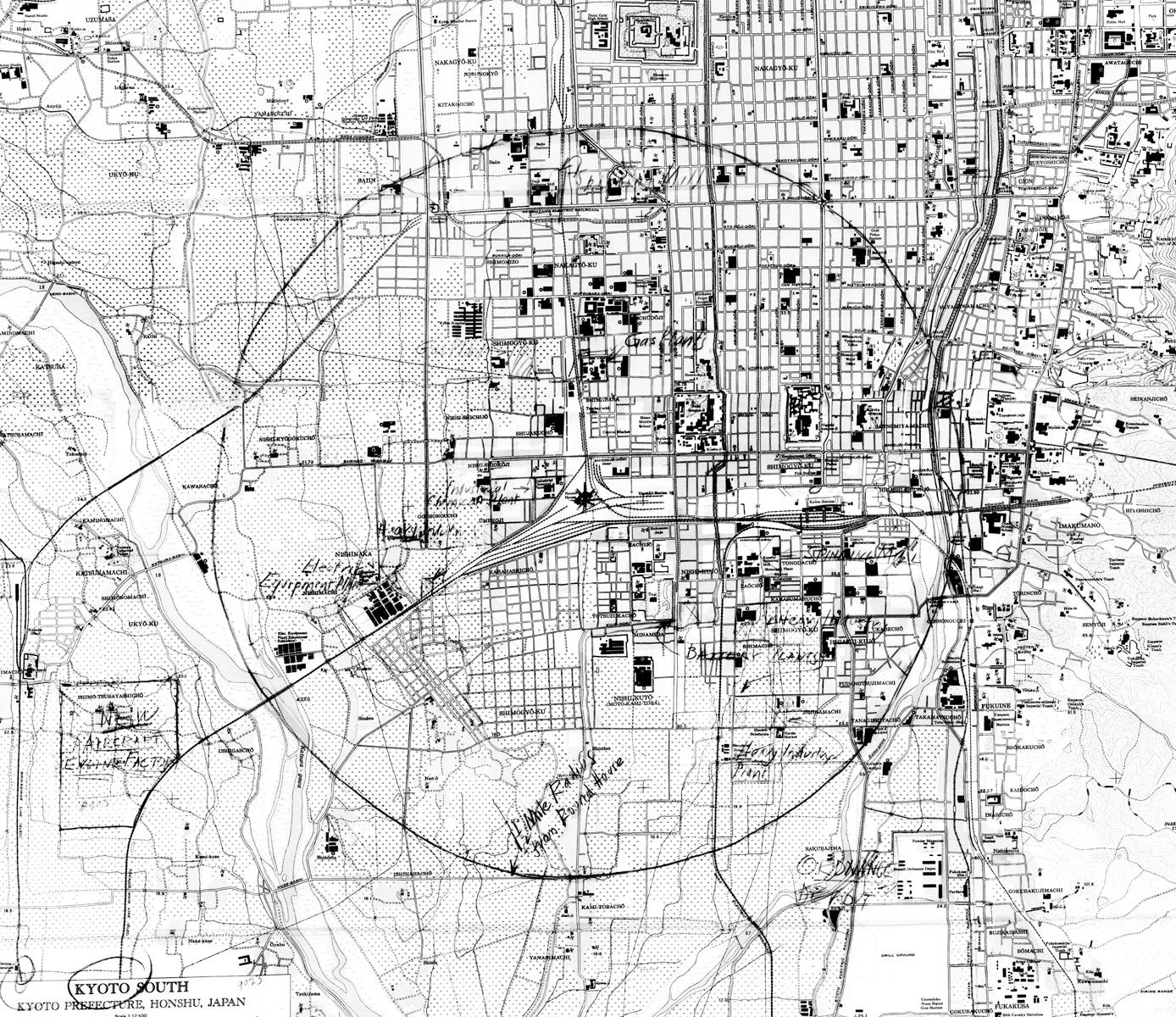

That he came under this misconception because of the one real “atomic decision” he made prior to the bombings, which was to countersign Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s drive to keep Kyoto off of the atomic target list, which Truman mistakenly understood as a choice between a city and a military base;

That he did not learn the reality of the situation until August 8, 1945 — two days after the attack;

That he had no understanding that a second atomic bomb would be ready to use within a few days of the first, and had no forewarning at all about the Nagasaki attack, which was already underway the moment he learned that Hiroshima was a city;

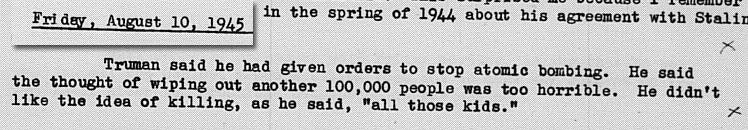

That his order to stop atomic bombings the day after the Nagasaki strike, which he told his cabinet was because of his horror at killing “all those kids,” constitutes his first truly informed major “decision” on the atomic bomb during World War II, and was a result of his fear that he had lost control of this new power;

That these sentiments persisted in his relationship with the bomb throughout his presidency, and led him to largely deny the military access to the weapons, to keep the use of the bomb “off the table” during the conflicts of the late 1940s and early 1950s, and is a major factor in the fact that Nagasaki was not just the second use of an atomic bomb in war, but the last use of one.

There is more than all of this — again, I look at all of his atomic opinions and decisions through the early 1950s — but this gives, I think, a flavor of what kind of book this is: a radical set of conclusions that should significantly change how we think about Truman and early atomic policy. My ultimate argument is that while Truman’s atomic legacy must include and be focused on the use of the atomic bomb against cities during the war, but he should also be given some credit for the fact that it never has been used in war since then.

If the above sounds crazy to you, and hard to believe without evidence — I understand! I would not have believed it myself prior to spending years researching it and thinking about it. If you are intrigued, please read the book — it contains all of the evidence which has informed my conclusions.

This book is written for a general audience (and, hint hint, would be a great gift for anyone interested in World War II history, presidential history, nuclear history, or Cold War history) but contains extensive documentation, discussion of sources and reasoning, and arguments that even seasoned scholars will find interesting and provocative.

I am also in the process of putting together my own personal page for the book, which contains interesting images and documents that I have come across in the course of my research. The page of images and photographs is basically complete — and the images I have used in this post come from there — and the documents page has gotten its first installation, with several more tranches of documents to be added over the next month.

If you are interested in the book, I strongly encourage you to pre-order it, as this will help make sure it gets the attention that I think it deserves. My goal in writing this book is not just to, you know, sell some books, but also to try and make a dent in the way in which we — especially Americans — think about the atomic bomb both in the past, and in present and potential future.

If you are interested in getting a signed copy of the book (for yourself or someone else), please refer to this page, which describes what the current options are for doing that.

I am going to be holding a talk and discussion of the book as part of the Nuclear Knowledges seminar series, at the Center for International Research, Sciences Po, Paris, on December 16, 2025 at 12-2pm ET (18-20hr CET). The event is open to the public if you happen to be in Paris (lucky you!), but it will also be live-streamed on Zoom. Here is the event link, and here is the registration (“inscription” in French) link that you will need to use for the Zoom link.

I've wondered about that remark for years now("You've got to understand that this isn't a military weapon,....") and the point in time that it occured at because it always made me consider that Truman had a much more complete understanding of the potential of the Bomb than FDR or that most people give him credit for. I get that Some of that understanding probably came from what Truman learned while the Truman Committee was doing its investigation, but I always had the impression that to FDR the Bomb was just another part of the global conflict that he was trying to manage: a major part to be sure but still just one major part among many. Truman on the other hand understood that the Bomb was in a class separate And beyond anything else that had come before, and that it Ought to be treated in a separate catagory on its own rather than simply as just another weapon in an arsenal.

Amazon UK has your book available by the author 'Alexandre Dumas' :)

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Masters-Atomic-Future-Navigated-Responsibility/dp/B0G54HFL6V/ref=sr_1_2?crid=3K4KX9H022PR0&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.IaNErS8UkBxWWhuqyNYBNUQxLjrahTvCVrFc9VkTmw4.JAeD01xaFIKLH7fHku3yEH4Kviea1G2mkoHKA2q_q-Q&dib_tag=se&keywords=the+most+awful+responsibility&qid=1765699870&sprefix=%22The+Most+Awful+Responsibility%22%2Caps%2C95&sr=8-2