Will the survivors envy the dead?

Tracing the origins of a popular trope about nuclear war

Is nuclear war worth surviving? Or, as it is often asserted, will “the living envy the dead?” This phrase, along with multiple variations, is a truism of anti-nuclear weapons discourse, and has been for some time.

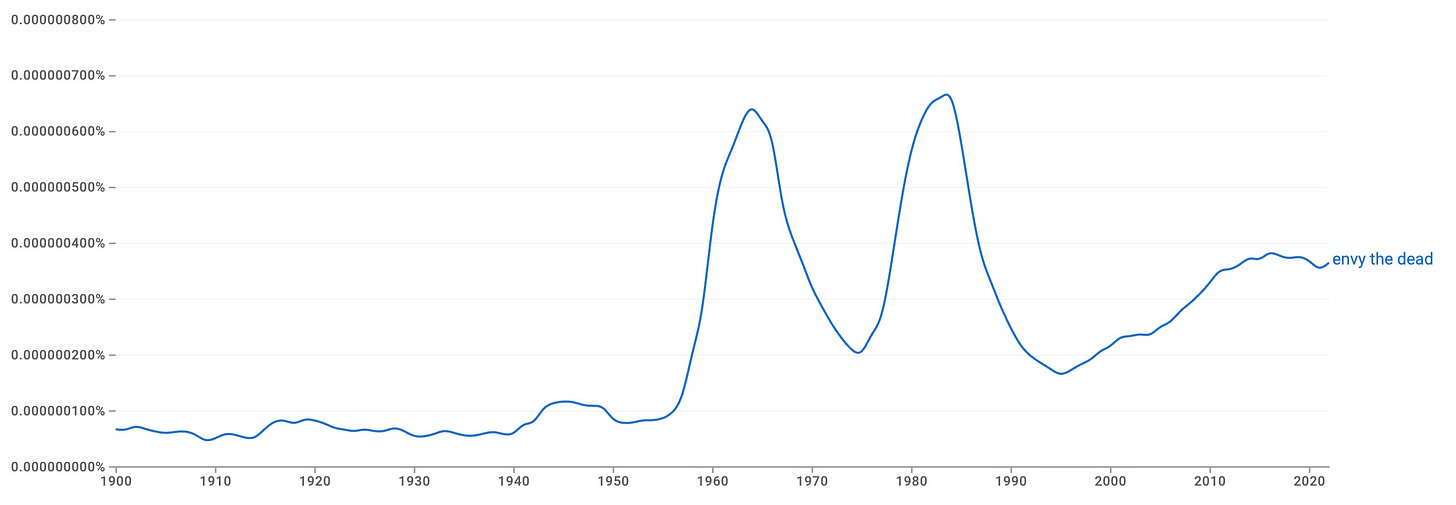

Google Ngrams, while hardly the arbiter of linguistic truth, gives some sense of the phrase’s use:

Different variations on the search phrase yield fairly similar results: some small amount of usage prior to the 1940s-1950s, then a huge spike in the early 1960s, and then the early 1980s, with the post-Cold War period showing a slow but steady growth.

As the fact that there is use of the phrase prior to 1945 indicates, the phrase pre-dates the nuclear age. The idea of the living “envying the dead” appears to derive from a sort of evocative, non-literal translation from the Book of Jeremiah, book 8, which says that:

1 “‘At that time, declares the Lord, the bones of the kings and officials of Judah, the bones of the priests and prophets, and the bones of the people of Jerusalem will be removed from their graves. 2 They will be exposed to the sun and the moon and all the stars of the heavens, which they have loved and served and which they have followed and consulted and worshiped. They will not be gathered up or buried, but will be like dung lying on the ground. 3 Wherever I banish them, all the survivors of this evil nation will prefer death to life, declares the Lord Almighty.’

The above is the New International Version of the English translation of the Old Testament. I am no Bible scholar, but a quick perusal of other translations does not reveal any that use the specific phrase “envy the dead.” Nor does “envy the dead” appear to be a direct translation from the original Hebrew.

But I suspect this is one of the primary origins for the “envy the dead” wording, only because one does find pre-nuclear invocations of this phrase specifically with Jeremiah.1 For example, here is the English translation of Stefan Zweig’s Jeremiah: A Drama in Nine Scenes (1922):

Touch me not. Better, far better is darkness, for the hour is at hand in Israel when the living will envy the dead, and when those that wake will envy the sleepers.

The other places I have found several pre-nuclear invocations of the phrase, without explicit reference to Jeremiah (but I assume may have connection to it), are in newspaper accounts of persecution in Europe at various times. In 1854, the Baltimore Sun carried an address from John Mitchell, an Irish exile, on the “relentlessly oppressed Irish nation,” in which he proclaimed (to “cheers” from the crowd) that:

…the social and political condition of Ireland is no whit improved, but is now precisely the same that it has been for fifty years—no better and no worse—insomuch that one might “envy the dead, who are already dead, more than the living who are yet alive.”

I’m not sure why the above address uses quotes for that part — again, it is not quite Jeremiah, and I haven’t find other uses of it. There is also an account from the Cincinnati Enquirer from 1905 about an anti-Jewish Pogrom in Odessa, in which the mother of a ten-year old boy says that:

We hear that nearly all the Jews in Odessa are slain. … All Russia is aflame. Blood is flooding Russia. There is wailing and moaning. The living envy the dead. I cannot write any more. I hear shooting and screams.

There are other accounts leading up until World War II that follow similar patterns. The point to be taken away here is that the phrase certainly existed, even if its exact origins and referent seem a little unclear. Personally, I think “prefer death to life” is not quite the same thing as “envy the dead.” But we’ll come back to that distinction.

Now let us move on to the atomic age. Searching through Google Books, ProQuest, Archive.org, and other such repositories of text, I found the phrase being used in conjunction with anti-nuclear war (i.e., pro-control, pro-peace, etc.) activism here and there at least as early as the late 1940s — not immediately after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Here is the progressive American physical sciences educator Oliver Schule Loud in 1948:

…it has been calculated by leading scientists that the first twenty four hours of an attack, a generation hence, upon the continental United States, by guided missiles carrying atomic war-heads, will leave our cities and industries in ruins and forty million of our citizens dead and dying. Our high command, to be sure, is preparing so that they can promptly mount a superior counter-attack in kind. But within a week of such warfare, all participating nations will have been destroyed. There will be no victors. The survivors will envy the dead as the fabrics of economies and social orders disintegrate.

And here, in 1951, is the socialist and pacifist speaker/political candidate/minister/etc. Norman Thomas testifying before the House Congressional Committee on Armed Services in 1951:

I need not take your time to tell you how completely destructive would be a new world war. The survivors might well envy the dead. We are concerned with a program to avert a third world war while we gain time to lay the foundations of peace.

And here is Thomas again, in the beginning of his 1959 book The Prerequisites for Peace, in a chapter titled “The Race to Death”:

Something new has happened in the world. It is now possible for the human race to commit collective suicide. It will do just that if it blunders into thermonuclear war, for which it is making frantic preparation. Already the Great Powers have in their possession the weapons, nuclear and biological, utterly to destroy civilization. Survivors of thermonuclear war, if such there are, will envy the dead. That world war might mean annihilation is acknowledged by scientists, rulers, and the people, yet the arms race goes on. It is a race which may end in the peace of universal death.

Now, do I think that these are the first people who used the phrase in an atomic context? Not really. I suspect that tracking down the first usage is hindered by sourcing issues — it may have been in speeches, talks, etc. that were not written down — and I don’t see much sign that anyone else thought that anyone, prior to the 1960s, was being particularly original or clever in using it. My guess, which is pure supposition, is that the phrase made its way into progressive circles over the course of the 1940s.

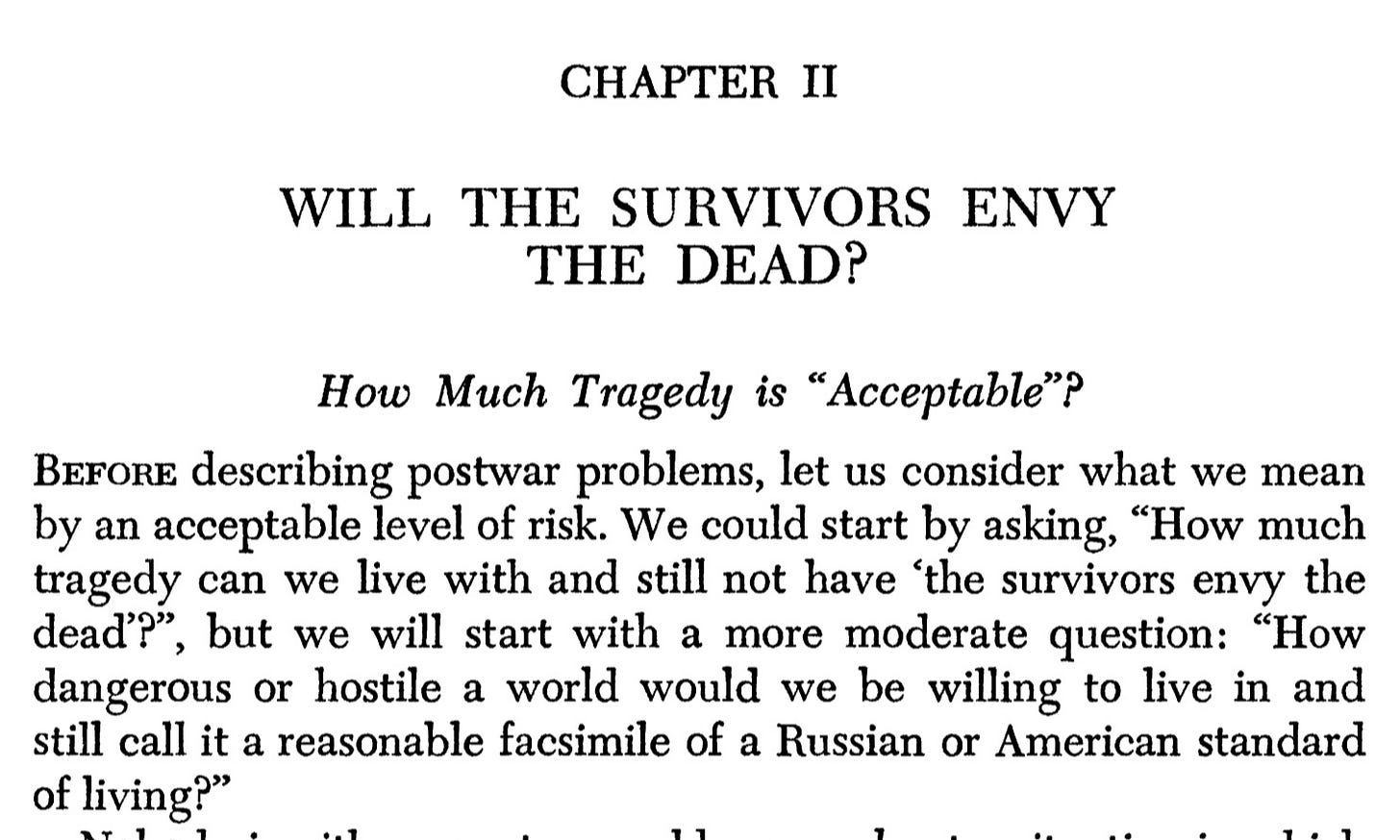

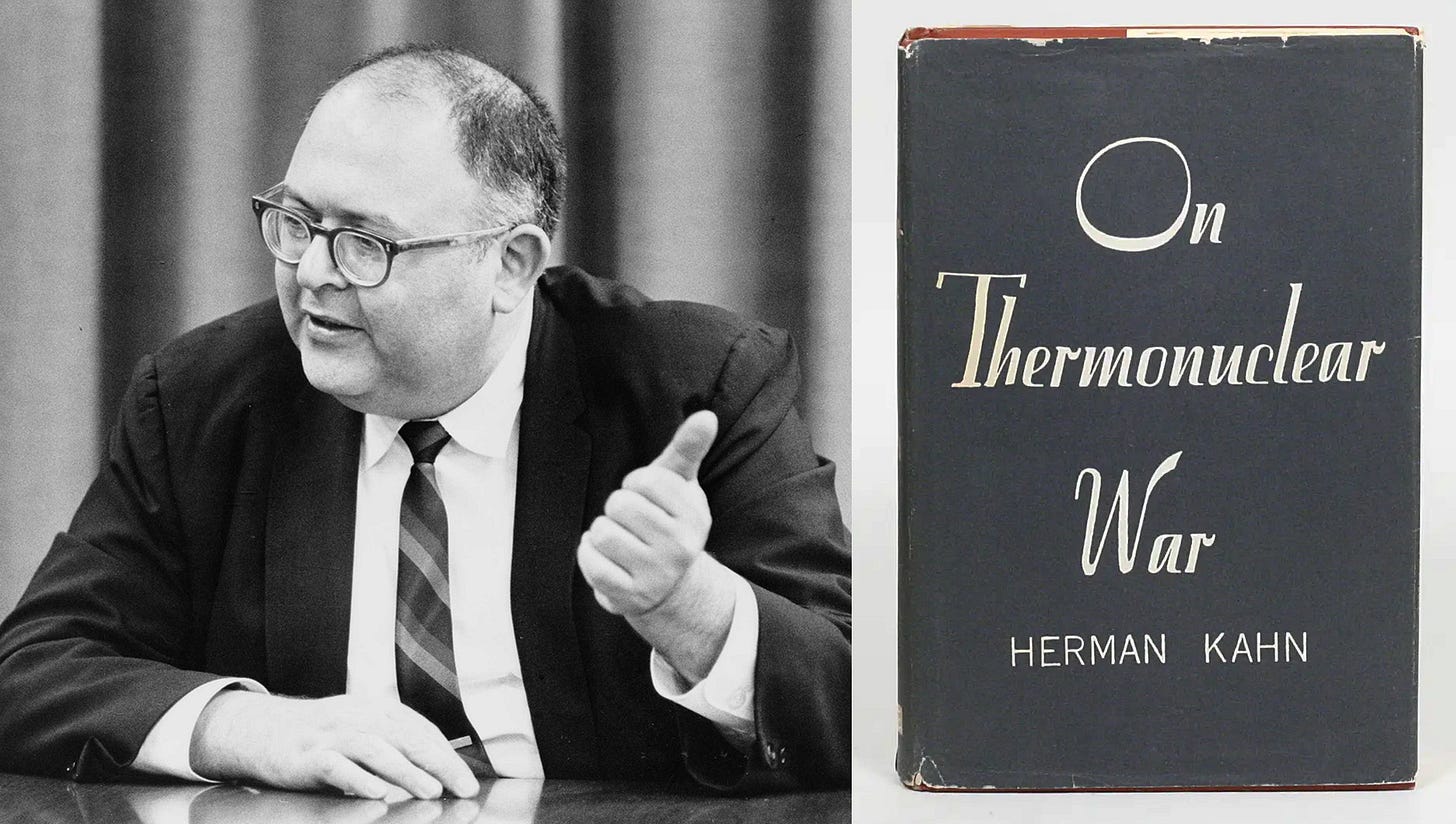

My sense is that the phrase did not become fully associated with nuclear war until the 1960s. Two things lead to this. The first was the publication of Herman Kahn’s On Thermonuclear War (1960), that most paradigmatic of nuclear strategy books directed at somewhat general audiences. Kahn’s book dedicates an entire chapter to the question of whether the survivors will “envy the dead.”

This is quite an interesting shift in framing. Instead of asserting that the survivors will envy the dead, Kahn tries to flip the idea around into a question: “How much tragedy can we live with and still not have ‘the survivors envy the dead?’?” He quickly reduces this to a more measurable question than one of envy, and to instead ask, essentially, at what level of nuclear war would it become impossible to consider one’s self (in some amount of time) as living to a comparable standard of living prior to the nuclear war.

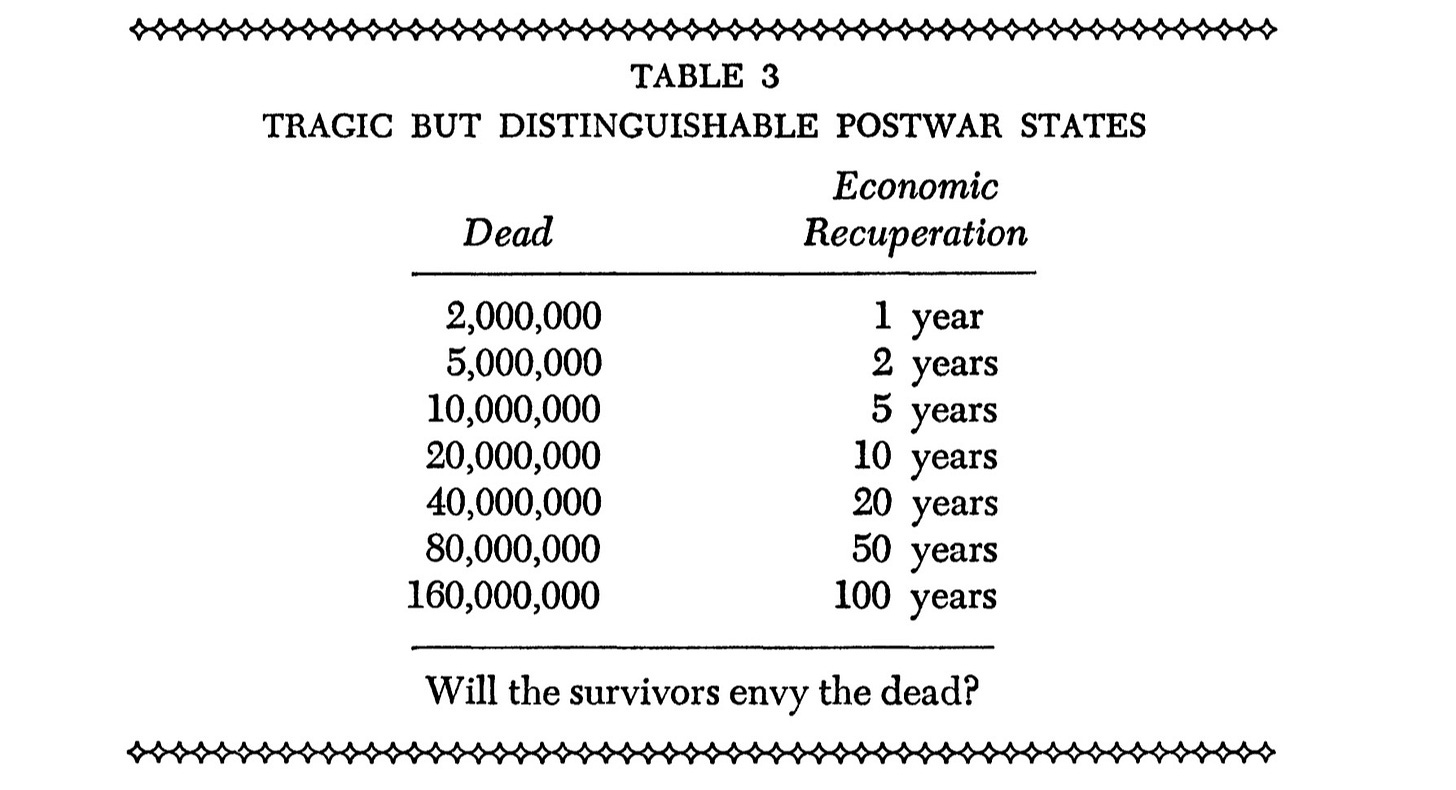

With this framework, Kahn is able to “attack” the question in a variety of ways. Ultimately, Kahn’s argument rests very hard on a table of “TRAGIC BUT DISTINGUISHABLE POSTWAR STATES,” showing different associations between mega-deaths and the time for “economic recuperation”:

And at the bottom, again, he adds the “envy the dead” question. Here is what Kahn says about the table and this framing:

Perhaps the most important item on the table of distinguishable states is not the numbers of dead or the number of years it takes for economic recuperation; rather, it is the question at the bottom: “Will the survivors envy the dead?” It is in some sense true that one may never recuperate from a thermonuclear war. The world may be permanently (i.e., for perhaps 10,000 years) more hostile to human life as a result of such a war. Therefore, if the question, “Can we restore the prewar conditions of life?” is asked, the answer must be “No!” But there are other relevant questions to be asked. For example: “How much more hostile will the environment be? Will it be so hostile that we or our descendants would prefer being dead than alive?” Perhaps even more pertinent is this question, “How happy or normal a life can the survivors and their descendants hope to have?” Despite a widespread belief to the contrary, objective studies indicate that even though the amount of human tragedy would be greatly increased in the postwar world, the increase would not preclude normal and happy lives for the majority of survivors and their descendants.

Kahn further says that he and his colleagues came to this conclusion “reluctantly,” because it felt so hard to believe.

If you’re familiar with Kahn, this is, indeed, classic Kahn. It’s a line of reason that feels pure and solid… so long as you don’t start poking it at all. There, to my mind, a vast difference between asking, “how long would the economy take to recover after a nuclear war?” and asking, “would survivors of a nuclear war envy the dead?”

In fact, I think there is actually a pretty big difference between asking, “would the survivors of a nuclear war think that the dead had an easier time of things” (what I think envy the dead implies in a literal sense) and asking, “would the survivors of a nuclear war literally wish for their own death/be suicidal?” These are quite different states of mind, as I see them. And they have more to do with psychological factors more than they do, say, economic recovery (of all things).

But let us put Kahn to the side for a moment, because this isn’t about him, really. This is about the phrase. My sense is that Kahn’s dwelling on it probably did much to associate the idea of “survivors will envy the dead?” with nuclear war in a broader cultural sense, even if — ironically — Kahn’s entire argument is based on showing that, with the right circumstances (and civil defense and shelters and so on) the survivors would not envy the dead. That is, I don’t think Kahn was particularly successful in a broader sense of convincing people that the survivors would not envy the dead, but I think he was probably the most to immediately credit for the phrase gaining a broader association with a post-nuclear existence.

But a funny thing happens between 1960 and 1963 or so — the phrase becomes very common in the West, but becomes almost exclusively attributed to Nikita Khrushchev. President John F. Kennedy, in his Address to the Nation on July 26, 1963 about the Limited Test Ban Treaty, is probably the original case for this attribution:

A war today or tomorrow, if it led to nuclear war, would not be like any war in history. A full-scale nuclear exchange, lasting less than 60 minutes, with the weapons now in existence, could wipe out more than 300 million Americans, Europeans, and Russians, as well as untold numbers elsewhere. And the survivors, as Chairman Khrushchev warned the Communist Chinese, “the survivors would envy the dead.” For they would inherit a world so devastated by explosions and poison and fire that today we cannot even conceive of its horrors. So let us try to turn the world away from war. Let us make the most of this opportunity, and every opportunity, to reduce tension, to slow down the perilous nuclear arms race, and to check the world’s slide toward final annihilation.

The question arises: did Khrushchev actually say this? Bartleby’s, in 1989, concluded that he had not: “No form of this quotation has been verified in the speeches or writings of Khrushchev.” But I suspect this reflects the limits of what was easy to track down in the West circa 1989, as opposed to reality.

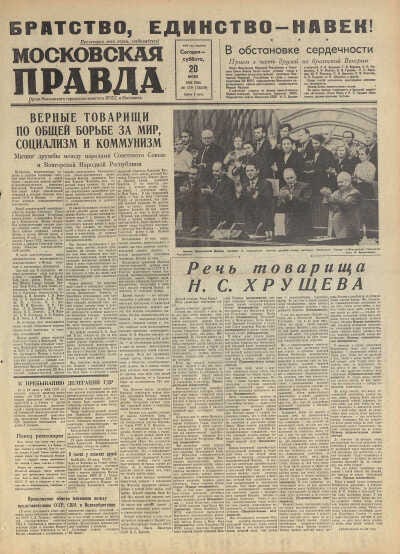

On July 19, 1963, Khrushchev gave a speech at a “Soviet-Hungarian Friendship Meeting,” which was reprinted the next day in Pravda. Here is an English translation from the Foreign Language Publishing House:

But when it is said that a people who had accomplished a [socialist] revolution should start a war that would be a world nuclear war, that they should start such a war so as to create a more flourishing society on the corpses of millions upon millions of victims, on the ruins of the world—that, comrades, is impossible to understand. Who would remain on this “flourishing earth” after such a war? We cannot agree with this contention.

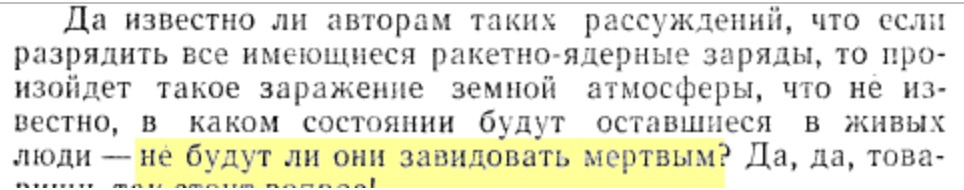

I wonder if the authors of these assertions know that if all the nuclear warheads are detonated the earth’s atmosphere will be so contaminated that nobody can tell in what condition the survivors will be and whether they will not envy the dead. Yes, yes, comrades, that is how the question stands.

The “authors of these assertions” is apparently a reference to a statement attributed to Chairman Mao Zedong (from May 1958) about the benefits of a nuclear war, and this entire speech was in the context of the emerging Sino-Soviet split. (The official response from Beijing, in late August 1963, was to assert that the Soviet view that nuclear weapons had “changed everything” was “the philosophy of willing slaves.”)

The exact, original Russian from the speech seems to be: “в каком состоянии будут оставшиеся в живых люди — не будут ли они завидовать мёртвым?” — literally, “of the conditions of the surviving people — won’t they envy the dead?”

What is different from Kennedy’s quotation of it is that Khrushchev’s formulation is a not an assertion, but a question — but it is a leading question, because, unlike Kahn’s version of it, it is pretty clear that the point is for you to agree that indeed, the survivors might envy the dead in this situation. So I think Kennedy’s attribution of the phrase to Khrushchev, a mere week later (!), is not incorrect, nor does he contextualize it erroneously, even if Khrushchev is not quite baldly asserting that “the survivors would envy the dead” in the original.

Did Khrushchev get the phrase from Kahn? I have no idea. I have seen it speculated that the Russian version of the phrase is more directly traced to a particular translation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, but tracing Russian origins of a phrase go beyond my ken. I think that Kahn is probably important in the Anglophone world for this association, and is why the Khrushchev quote would have been picked up on in particular. But who can say?

In any event, once you get beyond 1963, the phrase becomes quite commonly associated with nuclear war. It often gets attributed to Khrushchev directly, via Kennedy, which does not perfectly describe its origins and associations, but is not totally wrong, either.

So, to come back around to the main question at hand — whether Kahn’s or Khrushchev’s or whomever’s — would the survivors envy the dead in the event of a nuclear war? I think this very much depends on what one means by the phrase “envy the dead,” and I think it probably depends on who one is counting as among the “survivors.” Without being specific about those two things, the phrase is more evocative than useful. Nuclear war would be horrible and devastating and almost unthinkably destructive and wasteful.

Would the survivors literally prefer death over life? I am sure some would — because we know survivors of any kind of horror sometimes do. Would all survivors feel that way? Of this, I am doubtful. Not because the horror would not be great or that it would be bearable. But because, if we look at people historically, we see that the survival instinct is strong, and that people are remarkably resilient sufferers.

There are a few other Biblical references which sometimes come up in regards to this phrase, but they strike me as less direct as the Jeremiah quote.

Thank you for sharing the biblical references—interesting! one also needs to wonder if part of this meme was salted into the West as communist propaganda to discourage the use of nuclear weapons to counter a communist advance into NATO countries. One would need to look at Hollywood taking this to overkill with On the Beach or Threads (UK). Same could be said about the spread of the Nuclear Free Zone protests that spread throughout Europe and some of the West—was this initiated as a lever by the Communists and fellow travelers in order to make the US and NATO mothball its overwhelming nuclear superiority?

Ecclesiastes 4 seems a close match to your John Mitchell quote:

So I returned, and considered all the oppressions that are done under the sun: and behold the tears of such as were oppressed, and they had no comforter; and on the side of their oppressors there was power; but they had no comforter.

Wherefore I praised the dead which are already dead more than the living which are yet alive.