"Zero time was speeding toward me like a car you cannot dodge"

A gripping first-hand account of a nuclear test from 1957

One of the most infamous types of Cold War nuclear weapons testing performed are “military exercises,” where nuclear detonations coincided with troop movements, done in order to determine what impact the viewing of a distant — but not too distant — nuclear explosion had on troop morale, ability to follow orders, and ability to execute standard combat maneuvers. The fear was that perhaps soldiers would become shocked, overly afraid, and undisciplined in the face of such spectacle, with dire consequences for battlefield maneuvers in an age of tactical nuclear weapons.

Above: a 3.5 minute excerpt from an RKO/Pathé film of a “Desert Rock” exercise from the 1952, via the Prelinger Archive/Archive.org.1 This is not the detonation described below, but it’s one of the most evocative films of a nuclear test I have ever seen, as it gives a much better sense of scale than most test footage.

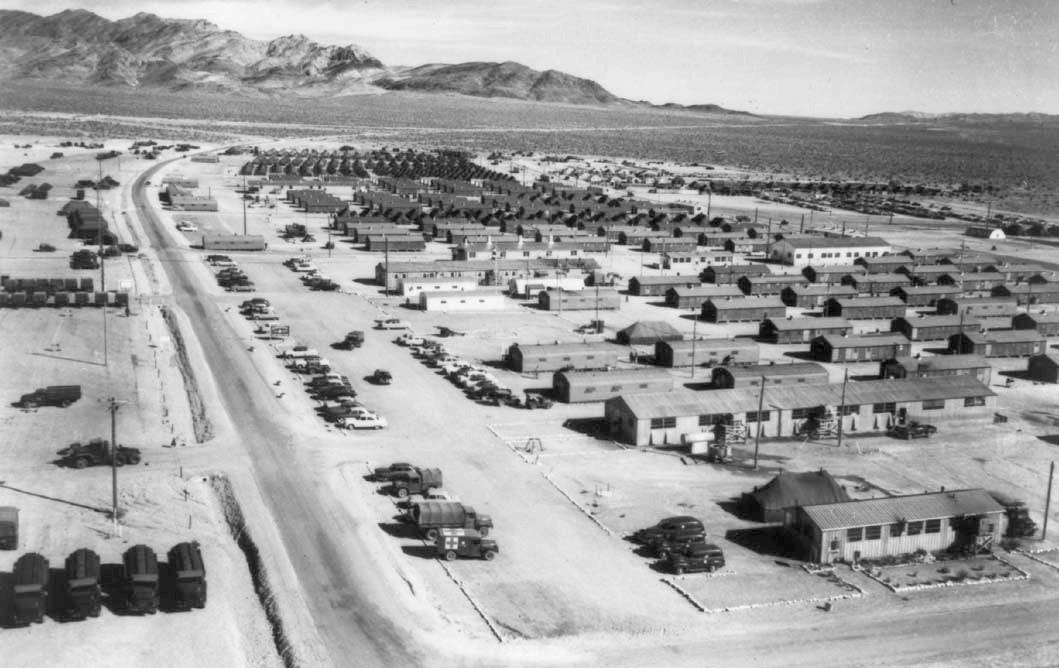

These “Desert Rock” exercises, conducted at the Nevada Test Site between 1951 and 1957, are “infamous” because of the large number of “atomic veterans” they created. Although ostensibly designed to be safe in terms of radiation exposure, there have been thousands of claims of subsequent cancers among this population.

What follows is an unusual and evocative first-hand account of a Desert Rock exercise, shot SHASTA of Operation Plumbbob on August 18, 1957, from one of the researchers, William E. Montague.2

This account comes from a longer report on the psychological impacts of the exercises, and is, I think, unusually well-written and compelling read for what is essentially a research report, and a snapshot into an unusual experience that may, with any luck, never be recaptured. I found it impossible to put down once I started it. I have transcribed it from a messy PDF and bad OCR, so apologies if any of the typos slipped through. Where possible I have tried to add simple annotations or links to thinks that might not be obvious.3

Saturday night, August 18, we were sitting around on the patio of the Officers Club about 2230 “socializing” and wondering when Shot Shasta would go. This was the 19th day, or so, that it had been postponed. A vehicle roared up. Loudspeaker called, “Attention all personnel! Attention all personnel! Shasta is on! Shot Shasta is on!”

We immediately went to tell the others. Then I went to bed for three hours so I’d be rested.

At 0130 on Sunday morning [Dr.] Boyd Mathers shook me awake and I was so jumpy I came up swinging. I dressed and went to the VIP mess here I had been told coffee was being served. I noticed they had real cloth table cloths. While having coffee and cake a major came in and said he thought it would go tonight; weather was good over the flat and it was very unusual to have a shot rescheduled to go at such a late hour, so the AEC [Atomic Energy Commission] must think conditions were just right.

I left the mess hall and [Dr. Robert] Vineberg drove up with a carryall (station wagon) full of our people. We drove out of [Camp] Desert Rock and passed through the check points at Mercury [base of operations at Nevada Test Site] & couple of miles up the road, then drove 25 miles to Yucca flat. We arrived at our observation point, which is called Goose Nob, at 0230, not to be confused with News Nob, which is nearby for wheels [VIPs] and reporters.

I had been there twice before, and both times the shot had been postponed at the last minute. Bob parked the vehicle and we climbed out for our third go at the thing. This time the loudspeaker was playing slow hill billy or cowboy music. The other times it had featured such things as Beethoven’s Tenth Quartet. Goose Nob is situated on the slope of a hill or mountain at the south end of Yucca Flat. A square pebbled area of about a hundred feet on a side has been leveled off and brightly illuminated by two enormous hooded lights on a thirty foot pole. In the forward portion of this square is the “pig pen,” as Vineberg called it, a fenced-in section containing twelve rows of 25 foot long wooden benches painted gray. I went through the opening and sat down on the rear bench. Soon Pete [Christian Peterson?] joined me. A couple of Army sedans were there at the site before us, and a few minutes after we arrived two buses of soldiers pulled up and the troops spread out over the area, some to talk, some to read and some to lie down on the benches and sleep.

I sat there and took notes and talked to Pete, who used to teach Physics. He pointed out the constellation of Cassiopeia to me, and we finally located Orion low on the eastern horizon under the half moon. we think we found Polaris, though the Big Dipper was too much for us. Pete said it was partly hidden by the ridge of mountains barely discernible against the night sky to our north across Yucca Flat.

At 0255 the music went off the air and a voice made substantially the following announcement: “This is Dragnet. Five minutes until H minus two hours.”

Three more vehicles arrived: a jeep, an ambulance and a sort of truck with a crane, perhaps for recovering any cars that should get stuck off the road. The men parked their cars and dispersed over the observation point. Some of the officers and men collected around the small snack bar building which, though well lighted and supplied with a telephone, contained no snacks or refreshments whatsoever.

The loudspeaker cackled on again: “This is Dragnet. Stand by for time hack.4 In one minute the time will be H minus two hours. H minus two hours ... thirty seconds ... ten seconds... five, four, three, two, one, hack.” At the instant of hack we saw a small, bright hemisphere of orange fire silently blossom and die far out on the blackness of Yucca Flat.

Then the voice continued: “Next time hack at H minus one and one-half hours. Next time hack at H minus one and one-half hours.”

“That was the metering charge,” I said. Pete had his watch out and was timing the interval until the sound of the explosion reached us. “That’s twelve hundred pounds of TNT”, I said. “At least that’s what I hear it’s supposed to be.”

Pete said that for the last two times we had come out to the site the charge had contained twenty-four hundred pounds. In any event, we never heard it. Apparently the wind was away from us. The first time we came to the site I had counted fifty-seven seconds before the sound reached us. With sound traveling at about a thousand feet per second I calculated the charge had been detonated about eleven and a half miles from us. On that first evening I hadn’t knows about the charge, and the flash had made me flinch my eyes away. I was set to hide my eyes from any nearly detonation and the TNT had triggered me off. “Well”, I said. “Since we couldn’t hear the metering charge, maybe that means the wind is right. Away from us and Las Vegas. Maybe they won’t postpone the shot again.”

A growly metallic voice from a jeep’s radio chanted: “Earthquake calling, this is Earthquake calling,” followed by some other words I could not distinguish.

The floodlights illuminated the grotesque little Joshua trees and low clumps of brush for about fifty yards beyond the wire down the slope to our front. Beyond the light the vast expanse of the valley was inky black, pinpointed here and there by the many-mile distant lights of a road marker, a tower, or a vehicle traveling on some late, pre-shot business.

Pete and I discussed the expanding universe and the red shift. The night was cool. At intervals we heard two other time hacks. We watched what we presumed was the light of a weather balloon ascending from Yucca Lake, a dry lake bed off to our right. The balloon seemed to drift very slightly to the south as it rose, its light blinking constantly.

At H minus forty five minutes all personnel were instructed to move into the wired-in area. A few troops and officers who bad been outside the wire came in and took seats. The voice from the loudspeaker instructed us regarding the operation.

“The shot you are to witness this morning is Shasta. It is expected that the yield will be approximately half of nominal.5 We are viewing the shot from a position approximately twelve miles from ground zero. Personnel wearing density goggles can observe the fireball. Personnel wearing goggles — approved four point two density goggles or higher — can observe the fireball. However, they must not look directly at the fireball until after the detonation — look to the right or left of the fireball. Look directly at the fireball only after the initial intensity of the light has faded. Personnel without goggles will turn and face away from the direction of the shot three to five minutes before zero and shield their eyes with either the right or left arm. After the shot you will be told when to turn around and view the fireball. This will be approximately five seconds after zero. In the event of a miss-fire remain in position with the eyes shielded until given instructions. When told to turn, you can turn and observe the fireball and the cloud. The cloud is expected to rise thirty to thirty-five thousand feet with fall-out to the west and north, then northeasterly at fifteen degrees.”6

The loudspeaker gave some additional information regarding certain projects that would track the cloud, then cut off. Vineberg said, “I’m cold!”

We noticed some vehicle lights coming back across the flat. I wondered if they had armed the device. Pete unwrapped a sandwich and offered some of it to the rest of us, but I was not interested. I noticed that the person two benches in front of me had brought a pillow and blanket and was making good use of them.

“This is later than we’ve ever been,” someone said. “Maybe they won’t cancel it this time.”

The loudspeaker came on again to tell us that the time was H minus thirty minutes and to repeat the instructions regarding the protection of our eyes. A jet whined high over us and looking to my right I noticed that the air strip was lit up. Immediately in front of us a group of six or seven soldiers was gathered out beyond the wire. Someone said they were Army photographers. Another jet went over. I noticed an increase in nervousness as the time approached. I wanted to face away even though it was much too early. I was afraid of a premature detonation. Those around me denied similar feelings, but I noticed some of them no longer looked in the direction of the shot. We sat leaning forward, looking at the ground.

At H minus twenty minutes I heard a background voice over the loud-speaker say to someone near the microphone, “It’s hooked up now, Boy!” Then the loudspeaker spoke to us: “This is Dragnet. In one minute it will be H minus fifteen minutes, and so on, with a time tone every minute thereafter.”

Pete said, “This is the tape. The machine is committed.” I smiled and thought of [Dr. Robert] Baldwin’s idea for a “manual override for electric safety.”

Two men were still asleep, at least ostensibly. Seasoned troops. Most of us were inclined to laugh at anything as time ran down. I gestured out toward the thing in the dark and said “Poof!” throwing my hands wide. Everyone laughed. I asked [Dr.] Ralph [Kolstoe] if we were going to go through with the “Shut up and deal” routine when everyone turned to stare at the fireball. We thought we would not.7

The time tones were coming every minute and with each one the tension went up a notch. At H minus eight minutes I stopped taking notes. I didn’t want to clutter up the subjectivity of the experience. At H minus five minutes we turned around on the benches without waiting for the order to do so and covered our eyes. I removed my glasses and held them firmly by the temple piece in my right fist. I buried my eyes is my left elbow and pressed my left arm tight against my face with my right fist. It was dark and lonely in there. I began to tremble. My stomach muscles knotted up. Then the tenseness spread to my chest muscles. I became irritated at myself and made a definite effort to relax, which relieved the muscular strain but did little to reduce my mind’s tension. I imagined running away, then thought of how trivial would be the increase in distance that I could add by running for the short remaining time, since a twelve mile distance already separated us from the device.

“H minus one minute.”

I pressed my arm tighter against my face.

“H minus thirty seconds.”

The awful, marching inexorability of the thing came over me. Zero time was speeding toward me like a car you cannot dodge. In the darkness I heard Boyd say, “It’s going to be too late to postpone it!” I thought rapidly for something witty to say, such as yelling “Shasta is postponed for another twenty four hours!” but gave it up.

“H minus twenty seconds. . . H-minus ten seconds. . . five, four, three. . . (I scrunched my eyes shut and pulled my arm in on them). . . two, one, zero.”

At zero time I saw, in the darkness, a dim far off pink glow that brightened and spread, held steady for a second, then dimmed and shrunk. I knew it was the light from the device and I knew how blindingly bright it must be to reach our eyes at all under such protection. It really felt as though nothing had happened — just the soundless soft pink glow. A voice behind me (probably someone who had been through the count-down for Diablo, the shot that was a dud) cried, “Yeah! It went off!!!”

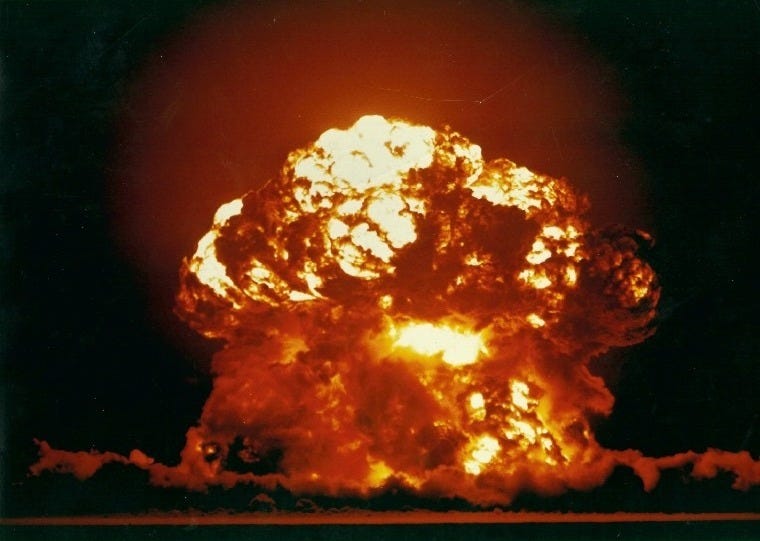

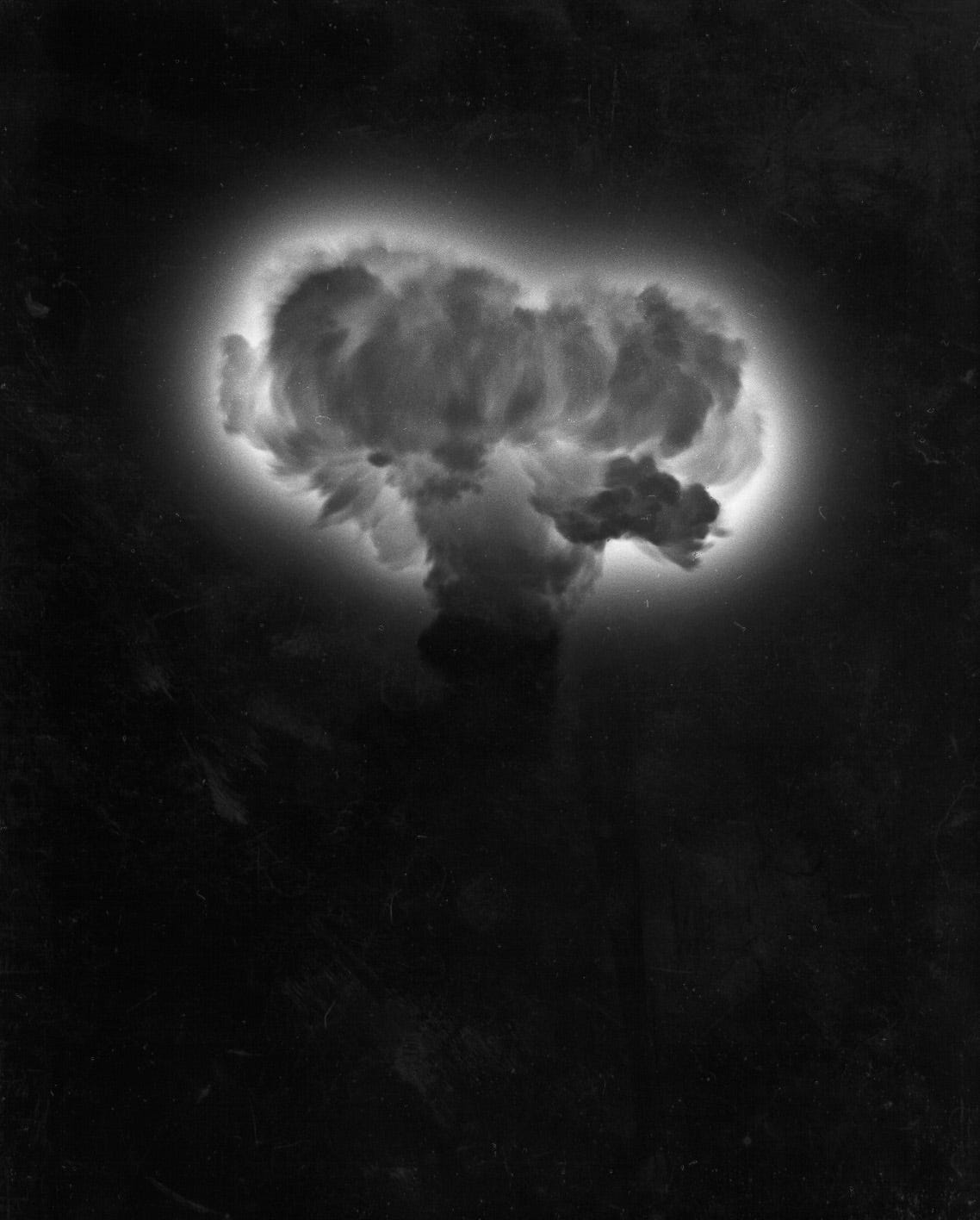

The loudspeaker said, “Turn!” As I uncovered my eyes I noticed it was still dark. Nothing had changed. Then we turned and I saw the thing that had been created. Far out across the miles of wasteland below us there was now dimly visible in the first morning light the golden fireball boiled and churned like a genii from a bottle, cooled to orange splotched with deep dirty brown, cooled to heavy violet and as it cooled its shimmering blue corona contracted and glowed around it. The fireball rises at a speed of sixty miles an hour, but at this distance its ascent seemed slow.

“Brace yourself,” the loudspeaker said. “The shockwave will be here any time now.”

We got set. Some of us debated whether the shock wave could exceed the speed of sound. I didn’t know whether to expect a crack, or a roar, or what. Then I heard what sounded exactly like a long line of freight cars “bumping” in the distance, a low quickly punctuated rumble that lasted three or four seconds and faded away. The cloud, subtending the same angle to the eye as a fifty-cent piece held at arm’s length, bad lost its brilliance. Raggedly oval, it lifted up from the desert. Beneath and around it the dust stood in almost static silhouette.

A quick bright flash startled me! Just the photographers with their flashbulbs. Then the floodlights were cut off, which made it easier for us to observe the mushroom. It was decidedly lopsided. Pete said that the stem of the mushroom should shear off. A weather balloon went up from the fat. Then a group of vehicles could be seen in the dim morning light taking off down the read to recover certain test equipment. A jet flew through the edge of the cloud, collecting samples. A moment later a rocket blazed upward and slanted into the cloud, disappearing abruptly as it entered. The cloud was very large now, much higher than the mountains in the background.

The radio in the jeep came on with a crackly last voice, “Earthquake-Two-Step-this-is-Earthquake-over.” At H plus fifteen minutes the first vehicles left our areas. “Well,” someone said. “Let’s go.” As we rose I noticed that the top of the cloud was pinkish white on its eastern face where it caught the first rays of the morning sun. Pete pointed out that the bottom of the stem was lifting clear off the ground and slanting away. He called this a good shear. On the ride back to Desert Rock and breakfast we watched the pink cloud over the hills behind us as it split slowly into three or four separate strata, each thinning and drifting away on the morning air. Frankly, it had been a little disappointing. But then, it was only a half-size shot, and we had been twelve miles away.

Britih Pathé’s newsreel service claimed this was the 28th US nuclear test in 1952, which would make it Tumbler-Snapper Fox if correct. The newsreel, however, is dated as being released on May 15, 1952, while Tumbler-Snapper Fox was on May 25, 1952. And apparently “tactical maneuvers” were not conducted after Fox, but were after shots Charlie, Dog, and George. So my guess is their count is off. Shot Dog is the only one listed as having Marines, and Pathé claims these were Marines. And… that’s as much time as I’m willing to put into identifying this exact shot.

There are a number of “William E. Montagues” in the world. My guess is that this is William Edward Montague, who got a PhD in game theory at University of Illinois,Urbana-Champagne in 1958, and who then went on to have a long career doing psychological research for the US military, among other things. But this is a supposition.

A “time hack” refers to a time synchronization event, named after a hack watch. So they are telling people who care that they can synchronize their clocks to the shot clock.

A “nominal yield” bomb in this period of the Cold War meant 20 kilotons of TNT equivalent, the same as the Trinity test and the Nagasaki bomb. It was much smaller than most deployed US nuclear weapons. The yield of Shasta was 17 kilotons, so closer to “nominal” than half-sized.

This turned out to be correct, per later fallout reconstructions of this shot.

Googling “Shut up and deal” mostly turns up references to the Billy Wilder film, The Apartment, which would not come out until 1960. A dive into Google Books produces one recurrent “joke” from the time: “Daddy, why can’t I go out and play like the other kids?” “Shut up and deal.” How that would work in this context, I have no idea…

Alex! Off topic question but one I’ve been curious about for a while. Are large data centers now something that could be considered a potential nuclear target?

Of course we can’t know for sure, but just wondering if it would be consistent with what you know of the targeting philosophy of our own country or what we know about other nations’? Would the answer depend on the purpose of the data center, eg AI or finance or military/government usage, or the size such as if they have a lot of power plants nearby?

I ask because I live in BFE now, except for the presence of several large data centers nearby! I know nuclear war isn’t the most pressing thing to be worried about (or maybe not, given the times?) but it’s definitely something I’m curious to know. :)

This reminds me of a story my father loved to tell. In the 1960s he was working on projects that tested electronic components using rocket sleds that ran at high speeds along a track at White Sands, New Mexico. One time, the rocket sled disintegrated, sending pieces of debris into the air. He saw a film of the incident afterwards and noticed that he, and all the other observers ducked--after the debris had already flown over their heads.