Katheryn Bigelow’s A House of Dynamite, released by Netflix in 2025, is the latest film seeking to spark a public conversation about nuclear weapons. There is much one can say about it, and my limited conversations about it with people in the nuke- and nuke-adjacent worlds reveal a mixed reception, and even more mixed interpretation.

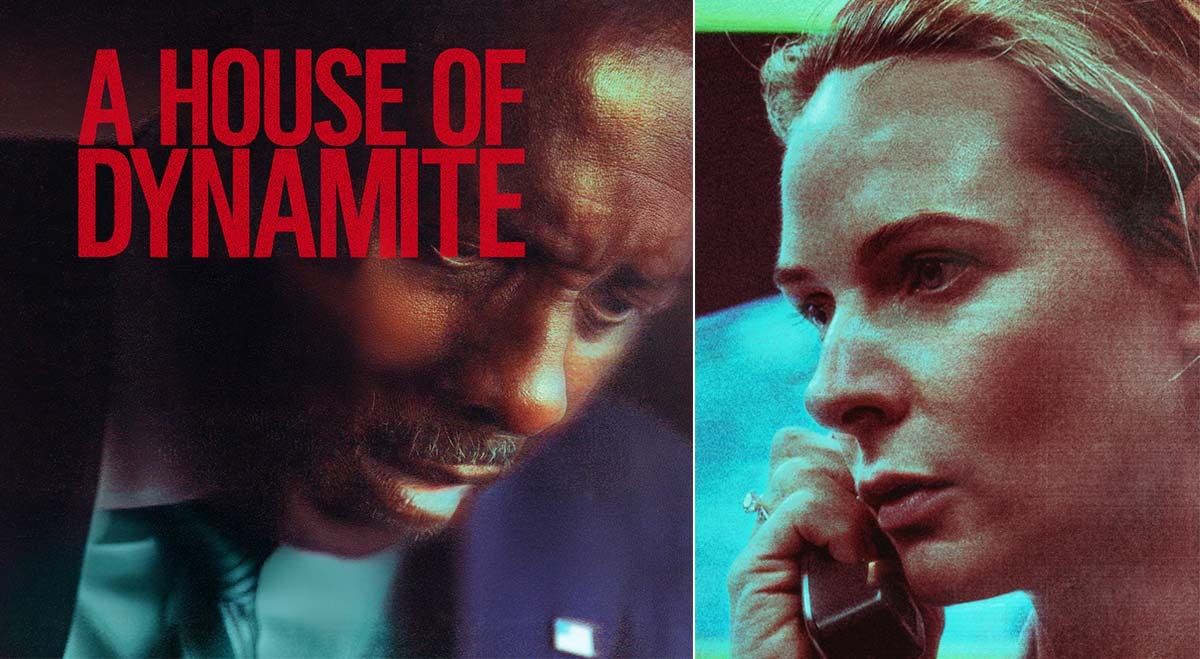

For the spoiler-free part of my review, I will simply say: as a film, I found it riveting, with good pacing and great acting. I thought many of the choices made in how to tell this story, and depict its people, were interesting. I thought it did an excellent job of showing the web of people, technologies, and institutions that make up the concrete reality of the American system of nuclear war. Ultimately, I think it is a timely film, even inasmuch as aspects of it, either deliberately or not — it was filmed before the November 2024 election — do not resemble our current political reality. I think it is definitely worth seeing.

But I have some additional thoughts, which necessitate many spoilers to the plot, so if you have not seen it and do not want to spoil it, you should stop reading here.

WARNING: YOU ARE NOW ENTERING THE SPOILER ZONE!

The plot of A House of Dynamite is relatively simple: on a random July day in an alternative timeline circa 2025, US Strategic Command (STRATCOM) detects an ICBM launch. The exact position and moment of launch is unknown, as the US satellites meant to detect launches have failed to detect it. At first it is thought to be some kind of North Korean ICBM test on a parabolic trajectory that will land in the sea of Japan. Over the next few minutes, it becomes clear that its trajectory is flattening, and it is projected to land somewhere in the United States. A US ballistic missile defense station in Alaska launches two ground-based interceptors (GBIs) at it. They miss. The missile is on a trajectory that will take in into the heart of Chicago, with millions of projected casualties.

The President is under pressure to consider a (nuclear) retaliatory response, while officials are evacuated to Raven Rock, a secure facility in Pennsylvania. The Russians and Chinese deny knowledge of who launched the missile, and the possibility of it being North Korea is discussed, as is the possibility that either Russia or China aided them by “blinding” the satellite that would have detected its launch. The film never tells us what the President does, or even whether the warhead goes off.

The structure of the film is unusual in that the main drama is only about 20 minutes long (reflecting the time of flight of the missile) and it loops three times. Each “loop” focuses on the perspective of different actors in the scenario, largely moving “up” the chains of commands, with the last “loop” finally showing the President (whose identity and responses have been largely obscured in the previous two loops). It is not quite Rashomon — all loops show the same “truth” — but it has a similar sort of intent.

In terms of its filmmaking, I thought this structure and approach worked well. It was gripping, and each loop did provide additional perspectives and information to the viewer, and it was a good cinematic answer to the question of “how do you make a feature-length movie revolve around the flight time of an ICBM?”

In terms of its accuracy, there is much one could talk about. In its favor, I think A House of Dynamite does a really good job of showing what the main structure of a nuclear crisis in the present day might look like, in terms of people and institutions. I think it does an excellent job of showing how much denial people would be in about the threat until it was almost too late to deny it further, and the ways in which the clinical, procedural, and game-theoretic approaches to this kind of problem would be intensely complicated (and impacted) by the very personal, psychological, and individual circumstances of people all throughout the chain of command.

There are certainly things missing, some of which were clearly cut or consolidated just to limit the complexity (e.g., the lack of a Secretary of State), and some of which are more important, but I think for your average viewer, this film already gives one a much better sense of the concrete realities of nuclear war than they otherwise would have had. I think that is a positive service that the film does.

The trickier inaccuracies are the deeper ones, the ones that feel necessary for the specifics of the plot, and thus make it feel somewhat contrived. For example, the launching of only two interceptors, which even characters in the film question the logic of. One understands why the writer/director did this: they wanted to emphasize (correctly) the deficits of ballistic missile defenses. But it strikes me as very unrealistic that, in this situation, where they believe a single nuclear-armed ballistic missile is aimed at a US city, that they would only launch two.

Could one have written a plot that still emphasized that ballistic missile defense is a losing game? Sure — but it would have required a very different setup. You could have multiple interceptors, but the incoming missile could use countermeasures (like decoys and chaff). Or you could have more than one incoming missile, and have a few get knocked out, but not all of them.

The problem with these plot changes, I think, are that they intercept with another major contrivance: the lack of attribution. While I would hardly put infinite faith in the US’s technical capabilities for identifying an incoming missile, it should have been better than in the film. “Blinding” a launch detection satellite is already quite a big leap, in my view, but even without that, there exist (I am told) technical means by which the US could, from the plume signature alone (which they do showcase briefly in the film), tell what kind of missile it is, in real-time.

The lack of attribution is necessary for this particular story, because the writer/director did not want it to be a simple story about specific bad guys, but about the general nuclear threat. I get that. But I’m not sure that works: nukes don’t just appear out of nowhere. Someone has to make a choice. Who made the choice? Why did they make it? What is the context? In the film, this is deliberately avoided — it is “context-free.” Which does not feel very realistic to me, or a very good way to think about the possible pathways to a nuclear use. One can compare this with Jeffrey Lewis’ excellent novel, The 2020 Commission Report, which is an in-depth, fictional account of a nuclear weapon detonation that is almost entirely about the kind of context that would produce such a thing in the modern world. A context-less nuclear attack is both a strange contrivance and a missed opportunity.

I have heard suggestions that perhaps there were more Hollywood reasons for keeping the attribution unclear: if you make the enemy China, then you limit your Netflix distribution possibilities, and if you make it North Korea, then you risk getting hacked. (I’m not sure if Russia gets ruled out for reasons like that, although I can see the argument that the complicated domestic political views towards Russia in the US right now would muddy the point the film is trying to make.)

The other major “accuracy” critique is that it feels odd that there were so many pressures, especially from the head of STRATCOM, on the President (played by the wonderful Idris Elba, and labeled in the credits simply as “POTUS”) to make an immediate decision about some level of a nuclear response. With a different “scenario” — e.g., a larger attack that might threaten US retaliatory capabilities — I could see those pressures being real. But for an unattributed single weapon, one whose consequences are not fully predictable before it detonates (or doesn’t),1 while I can believe there would be some voices for coming up with some kind of “immediate” response, I think the bulk of the weight would be against a nuclear response (and against who!?), and there would be no real reason (other than potentially a perception of political pressure) for the decision on any response to be made in minutes. The “making a decision” in minutes scenario does exist, to be sure, but this scenario is not that scenario.

More generally, my biggest concern and critique about the film is its overall “scenario.” The “bolt out of the blue” scenario, which historically has also been called an “atomic Pearl Harbor” or (later) a “nuclear 9/11” scenario, is one in which the United States has been minding its own business when suddenly it is attacked in a way it is not prepared for.

This has been a fear of the military and think-tank analysts in the United States since the Soviet Union developed a nuclear arsenal. It is why things like the “nuclear football” got developed, as well as weapons systems with fantastically (and perhaps dangerously) rapid response times, and nuclear-armed submarines, and so on. It is a fear that usually (but not always) comes from hawks, not doves, and there have been many iterations of it over the years.

Such fears are often invoked to justify the need for new systems, new capabilities, and — often — missile defenses. It is a scenario that generally implies a moral blamelessness on the part of the United States, rather than acknowledging that it likely would have a role to play in whatever escalation occurred, and implies a total moral debasement (and high tolerance for risk) in American adversaries, who are willing to gamble their entire nations on the possibility that they might catch the United States unaware. It is the fear that makes you put weapons on hair-trigger alerts, under the belief that the sneak attack could come at any moment, and without any warning.

I do not think that the director or screenwriter are hawks. To the contrary, they seem to see this as an anti-nuclear film, one whose ultimate message is that these weapons are dangerous and that their risk is uncontrollable. And there have been, in the past, doves who invoke the “bolt out of the blue” scenarios as a means for arguing against the possibility that nuclear war could be rationally avoided.

Ultimately, it would be very interesting to me to see how “lay” audiences view this film and its message. I could imagine a study, one that looked at people’s attitudes before they watched the film, and then immediately after they watched it, and then maybe a follow-up several months later to see what impression still “stuck around,” if any do. What I’d be interested in knowing is whether it caused any “movement” one way or the other on questions about nuclear weapons, their dangers, what the likely scenarios might be for their usage, the question of disarmament, and specific policy proposals like spending trillions on missile defenses. Most importantly, I would be interested in knowing what they think the “remedy” would be for the problem posed by the film.

I can’t predict how such audiences would view the film — I am not the target audience, I acknowledge that — but I fear that one of the main responses that Americans might have in particular is that the “remedy” for the situation outlined in the film would be to just build more missile defenses. The film doesn’t really discredit missile defense at all; it suggest that the current success rate of an interception is about 60%. That itself is probably too high a number, one derived from controlled tests, and not against serious countermeasures.

Americans are very prone to believing that with enough money, a merely “technical” problem like this could be solved. And maybe they can be! The film does not give what is, to my mind, the more serious arguments against ballistic missile defense: that the inevitable response to them by an adversary would be to either not rely on ballistic missiles for their nuclear deterrent posture, and/or to develop offensive ballistic missile capabilities of such a size that they would overwhelm such a system. And that is exactly what we see both Russia and China doing today, in part in direct response to US investments in ballistic missile defenses.

Ballistic missile defenses, in other words, don’t “solve” the problem of nuclear weapons risks at all: they may in fact make them worse, as they encourage larger and “weirder” arsenals (drone submarines, hypersonic launch vehicles, possibly smuggled weapons). And, of the utmost importance, there seems to be no reason to think they have a stabilizing effect: they encourage both the United States and its adversaries to engage in riskier behavior and expensive arms races. (And I suspect the latter is very much a “feature” and not a “bug” in the minds of the generals and contractors who argue for these systems.)

Did you get that message from this film? I didn’t. Could one imagine a film that did get this point across? Sure: but it would require a very different “scenario.”

But I could be wrong about how others read it. Again, I am not the target demographic. I suspect that, like basically everything about nuclear weapons in the world, the response will be very demographically rooted: people who lean “dove” on nuclear issues are likely to read it differently than those who lean “hawk,” and Americans are likely going to read it very differently than Europeans, and so on.

One idea that did occur to me recently when thinking about it, is that some of the “contrivances” of the plot could be addressed with one simple “theory”: that the missile is in fact an American missile, being launched as part of some Tom Clancy-ish conspiracy plot by the US military (for whatever nefarious aim). That would explain the “blinding” of the satellite, the relentless pressure on the President from everyone connected with the military for a massive escalation, the underwhelming effort on the interceptors, and maybe even the actions of the Secretary of Defense (who perhaps was dimly aware of the plot, but did not know its target, and was suddenly stricken with guilt). It’s an elegant solution, really… but I don’t actually think it was the goal of the creators of the film. But if I were going to write a fourth “loop” for it, maybe that is the approach I would take, a big reveal that made all of the nit-picking critics suddenly realize that they were simultaneously right and wrong!

Will A House of Dynamite join Dr. Strangelove, Fail-Safe, and The Day After as an important touchstone for thinking about nuclear weapons in our time? I have no idea. Culture works in mysterious and complicated ways. Do I think its contribution will be ultimately positive or negative? I have no idea. It will depend on whether it resonates at all, and what message people take from it. I will say that I am, ultimately, glad that it was made, because I think it does do a lot of positive “good” with respects to giving a deeper sense of the tangible, concrete realities of nuclear weapons and nuclear systems. I do hope it is financially successful, because that might mean that more films could be made on these topics. I just hope that this isn’t the “last word” on this issue for another two decades or so.2

And here is another nitpick: the film consistently implies that there would be 9 million casualties from an attack on Chicago. For that to happen, every single person in the Chicago metro area would need to be a casualty. This is not how weapons work. Even a 5 megaton missile, accurately placed on the heart of the city and detonated at a height to maximize civilian casualties, would “only” create around 2.8 million casualties, according to the ever-authoritative NUKEMAP. Even the full-scale, 100 Megaton Tsar Bomba “only” gets you 6.5 million casualties in such a situation. A more “realistic” warhead size for an SLBM, something in the neighborhood of 100-400 kt, gets you about 1.6 million casualties. Note that casualties are fatalities plus injured. Depending on the weapon used, the fatalities range from being 25% to 50% of the total casualties. This does not include longer-term casualties. I am assuming an airburst in these cases, which would maximize immediate damage and not produce a lot of fallout casualties. A surface burst of a 5 Mt warhead on Chicago might produce around 1.8 million casualties and a fallout plume that could deliver dangerous levels of radiation several hundred miles downwind, which, depending on the atmospheric conditions and actions people downwind take, could either result in many additional casualties, or few (e.g., if it happens to just blow out over Lake Michigan).

Does this matter? To my mind, yes and no. Yes: the fact that they exaggerate the casualties doesn’t really help anything, and it also implies that there are no mitigation efforts possible whatsoever. No: even these “reduced” numbers are still horrifying. If I had been an advisor on the script I think I would have had them say: “There are 9 million people in the Chicago metro area. Depending on where the bomb goes off and how powerful it is or isn’t, we’re talking about potentially millions of casualties.” That would be “accurate-enough” and still be plenty awful.

(Hey, Hollywood screen writers and producers… if you want someone to give your scripts a once-over for things like this, just get in touch! I’m also happy to put you in touch with other experts I know who specialize in other aspects of nuclear matters. We’re eager to help!)

The last serious “nuclear weapons threat” fictional film was, I believe, the adaptation of Tom Clancy’s Sum of All Fears, released in 2002, which was about the threat of nuclear terrorism. (I am leaving out films where the nuke is essentially a MacGuffin, like 2018’s Mission: Impossible — Fallout).

Good analysis that addresses in much more detail some of the issues I raised in a shorter review in the Bulletin (https://thebulletin.org/2025/10/what-we-should-be-talking-about-after-watching-bigelows-a-house-of-dynamite-nuclear-thriller/). One thing I would add is that the movie depicts the "use it or lose it" pressures a President might feel, albeit in a different scenario. Those pressures are the result of choices about our nuclear force structure that are designed to make nuclear deterrence more credible but also make nuclear crises less stable and more dangerous.

As a long time nuke nerd with a background in both science and American studies, this film made me extremely angry. And that is because of the glaring and utterly needless plot holes taking me out of the "suspension of disbelief".

The worst one is how it is bending over backwards to treat a threat that is manifestly NOT a "use them or lose them" situation as if it were.

Call me a nitpicker, call it style over substance but that is an insult to the viewers' intelligence.

If you want a "use them or lose them" situation in your movie, just WRITE ONE into it. Somebody please explain to me why they didn't. It would not have made a single difference to the production costs even. I'm just not gonna point out all the other nonsense here.

And it could have been so impactful. Can probably STILL be. Cause all the people depicted handling the crisis are normal professionals. You know? The type of government officials that have by now all been fired. All that is left currently in the situation room to manage a crisis like this , the people that would take all those decisions under extreme time pressure, are coked-out lunatics, utterly demented Nazi clowns, accelerationist billionaire junkies trying to bring about Christian apartheid apocalypse, and demented old codgers.