Irradiating the planet

Los Alamos scientists calculate the limits of radioactivity, 1947-1949

How many nuclear weapons would it take to make the world dangerously radioactive for human life?

This was a real question that Frederick Reines, a 30-year old theoretical physicist at Los Alamos was contemplating in the spring of 1947.1 The result of his work is a report that I recently received as the result of a FOIA request I made to the National Nuclear Security Administration: “Radioactive Pollution of the Earth’s Atmosphere,” dated March 25, 1947.2

Reine’s paper is an interesting one, and the timing is interesting as well. This is not long after the US Atomic Energy Commission took over the operation of the American nuclear infrastructure, and Los Alamos was on a more firmer postwar mission than it had been in the first year and a half since the end of World War II had put its future into limbo. They were now, truly and unambiguously, in the business of building up a postwar nuclear arsenal, even if the question of international control of nuclear weapons had not yet been settled.

So it was perhaps appropriate that they began to contemplate a truly dark, future question about what a much larger nuclear war might look like globally. Reine’s study was a very preliminary and in many ways oversimplified one, but it may have been the first to really look at the question in a structured way.

The basic question Reines is tackling is how the ambient radioactivity of the Earth’s surface would be impacted by the detonation of vast numbers of atomic bombs. His introduction makes clear that he is well aware that this is a very rough calculation, one that does not take into account the ways that meteorological conditions would affect the movement of radioactive materials globally, or the fact that the weapons would be detonated in different locations and at different times.

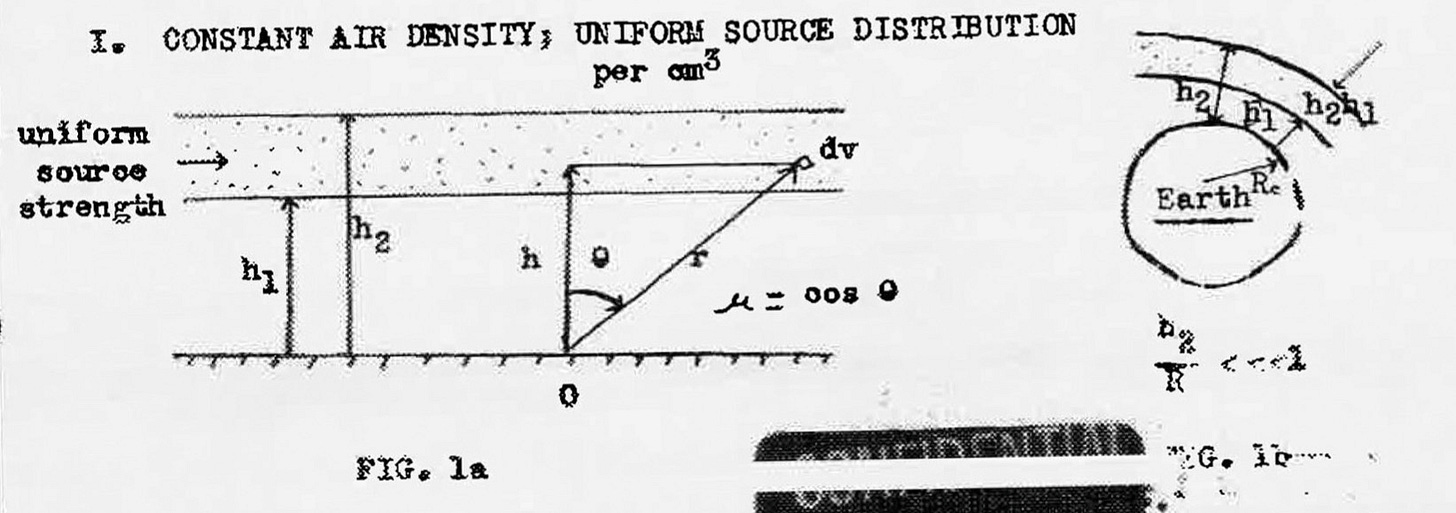

Reine’s model, as I understand it, first looks at the total radioactivity produced by the detonation n number of Nagasaki-type atomic bombs, looking exclusively at the gamma emissions of their fission products, the most intense part of nuclear fallout.3 He then asks, if those radioactive byproducts was in a spherical shell around the Earth — think of it as a uniform layer of clouds — and falling down over time, what would the exposures be for people on the ground?

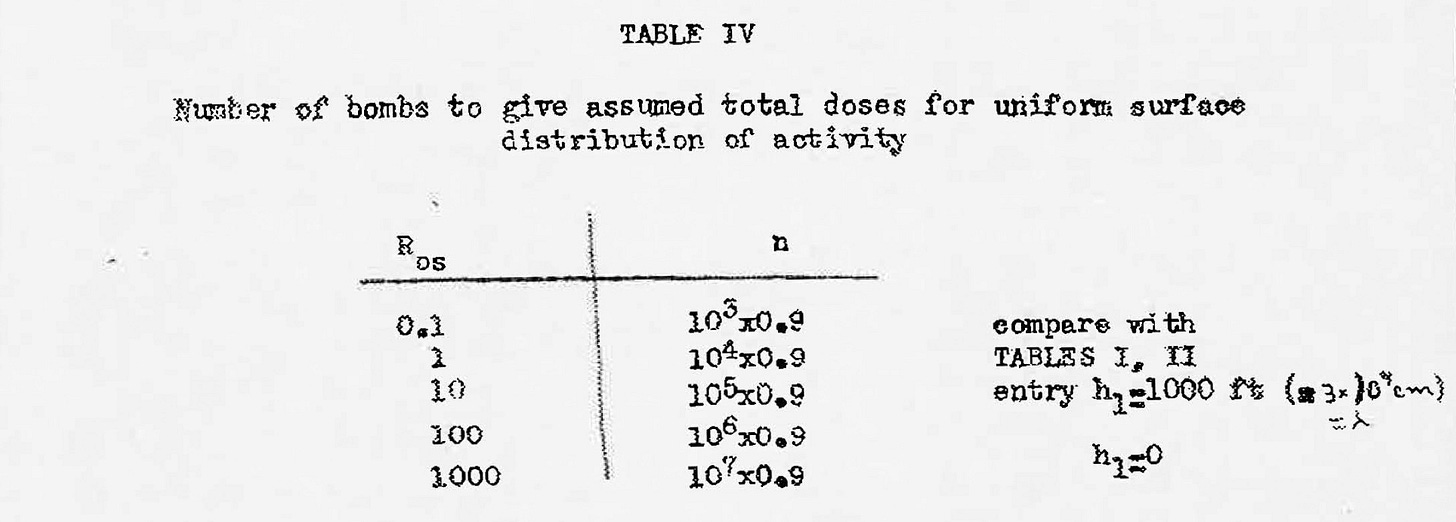

From this he produces several tables that give the radioactivity at a given point as a result of a given number of bobs and the altitude and height of the radioactive “shell” around the Earth. The culmination of this, as I read it, is a table that gives the “number of bombs to give assumed total doses for uniform distribution of activity.” At left, what he has labeled as R_os, is the total radioactive dose received on the ground, globally, in Roentgen units. 100 R produces radiation sickness and is where long-term cancer effects are very unambiguously seen in the data from Hiroshima and Nagasaki; 500 R is considered to be probably fatal; 1000 R is definitely fatal. 10 R would increase one’s lifetime fatal cancer risk a bit but should be otherwise unnoticeable.

The other column, n, refers to the total number of Nagasaki-style (20 kiloton or so) bombs that would produce the dosage. So for a uniform, global dose of 100 R, you would require 0.9 x 10^6 = 900,000 Nagasaki bombs. Which is a phenomenal number of Nagasaki bombs. That does, however, work out to “only” 18,000 megatons, which, in the thermonuclear age, is not so much after all — that is less than the peak megatonnage of the US Cold War nuclear stockpile.4 So while Reines’ conclusions are, in 1947, fairly optimistic at a time when the global nuclear numbered in the dozens and the weapons were all Nagasaki-style, projecting only 15 years or so into the future, they were more troubling.

In April 1947, the top-secret Manhattan District History chapter on technical work at Los Alamos recorded a different conclusion to the same question:

The most world-wide destruction could come from radioactive poisons. It has been estimated that the detonation of 10,000 – 100,000 fission bombs would bring the radioactive content of the Earth’s atmosphere to a dangerously high level.5

This sentence is uncited, so it is not clear where the calculation comes from. If it is from Reines’ report, it would only work if “dangerously high level” was defined as being well between 1 R and 10 R. That’s not high-enough for worldwide extinction — this is not an On the Beach scenario — but that would be a high-enough level that one would expect the global cancer rate to rise.

The other report that I got from the same FOIA request was from a slightly later period. This one was written by Ernest C. Anderson, a graduate research assistant who worked with Willard Libby on his pioneering development of the carbon-14 radioactive dating technique. It is perhaps appropriate, then, that he was assigned to update Reines’ calculation, taking into account new weapons possibilities: “Radioactive Contamination of the Atmosphere by Super Bombs,” dated November 29, 1949.6

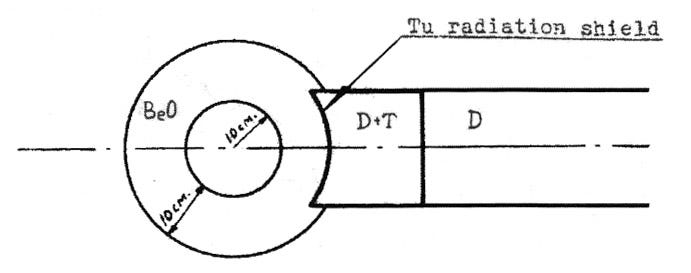

As the title suggests, this is concerned with the “Super,” their term at the time for thermonuclear weapons, or hydrogen bombs. This report was written during the H-bomb debate, which would be resolved in late January 1950 with Truman giving the project the go-ahead. At this point, they did not really know how to make Super bombs, and the Super being conceived was what later became referred to as a the Classical Super (and would ultimately be proven to be an unworkable design).

Anderson’s approach was a bit different than Reines’. They didn’t actually know how to make (much less have) a Super in 1949, so they didn’t have precise data to compare it to. But they understood that a Super as they conceived it then would produce a lot of neutrons, which could activate (make radioactive) a lot of otherwise stable atoms near the explosion, particularly nitrogen in the atmosphere (which would create radioactive carbon-14), and would also potentially create a lot of additional fission products. Unlike Reines, Anderson was attentive to the biological aspects of fallout — something that was much better understood in 1949 than in 1947, and is probably reflective of Anderson’s deeper experience modeling radioactivity in general.

Anderson’s assumption was that the Super would be about 1,000 times more powerful than the stockpiled atomic bombs of 1949, and so around 40 megatons each. He then goes through a series of equations looking at how many neutrons would produced per Super detonation, and how many of these could produce carbon-14, and how much of that radioactive substance would likely end up in the human body.

He also looked at fission products, which gives some interesting insight on their ideas about the Super at the time. According to Anderson, a workable but “crude guess” at how much “active material” it would need to start the Super reaction was 80 kg of fissionable material — which is a lot, about 25% more than the amount used in the very-inefficient Little Boy bomb. This is consistent with some other accounts of the early Super work, which imagined that a massive gun-type device might be needed to initiate the reaction properly.

As essentially all of this fissionable material would fission under the neutron flux of the Super, it would mean all 80 kg would be turned into fission products. By comparison, a “normal” atomic fission bomb at that time would only release about 2 kg of fission products (corresponding to a ~40 kiloton yield).

Anderson further assumed that this 80 kg would be all of the fission products produced, and that no materials would be used that might deliberately create more fission products or induced materials. In reality, that is not how hydrogen bombs were designed — they deliberately captured the neutrons from the fusion reaction and used them for further fission reactions.

Ultimately he concludes that 1,200 Super detonations “could be tolerated” without raising the background radioactivity beyond the “tolerance dose,” which was the maximum permissible dose for radiation workers at the time. He does not calculate any higher doses than that — which is a bit of a shame. At 40 Mt each, that does add up to a respectable 48,000 megatons, so perhaps he figured that he had made his point that the world was not in imminent danger of irradiating itself to death as the result of the Super.

But one should remember, though, that Anderson was only using a figure of 80 kg of fissionable material per Super — so these are very “clean” weapons, with only about 1.4 megatons their energy coming from fission. So another way to read his figure is that it is more like 1,700 fission megatons to reach “tolerance dose,” which is a much more, er, achievable number.

It is of some interest that a different paper tackling the same question, but using some different assumptions, was prepared in early December 1949 for President Truman by the Atomic Energy Commission using 10 Mt Super (still nearly all fusion) as its benchmark, and concluded it would take around 50,000 Supers exploding to hit the “danger point.” I do not think that this had any impact on Truman’s thinking, but it is interesting to see how these kinds of models were deployed.7

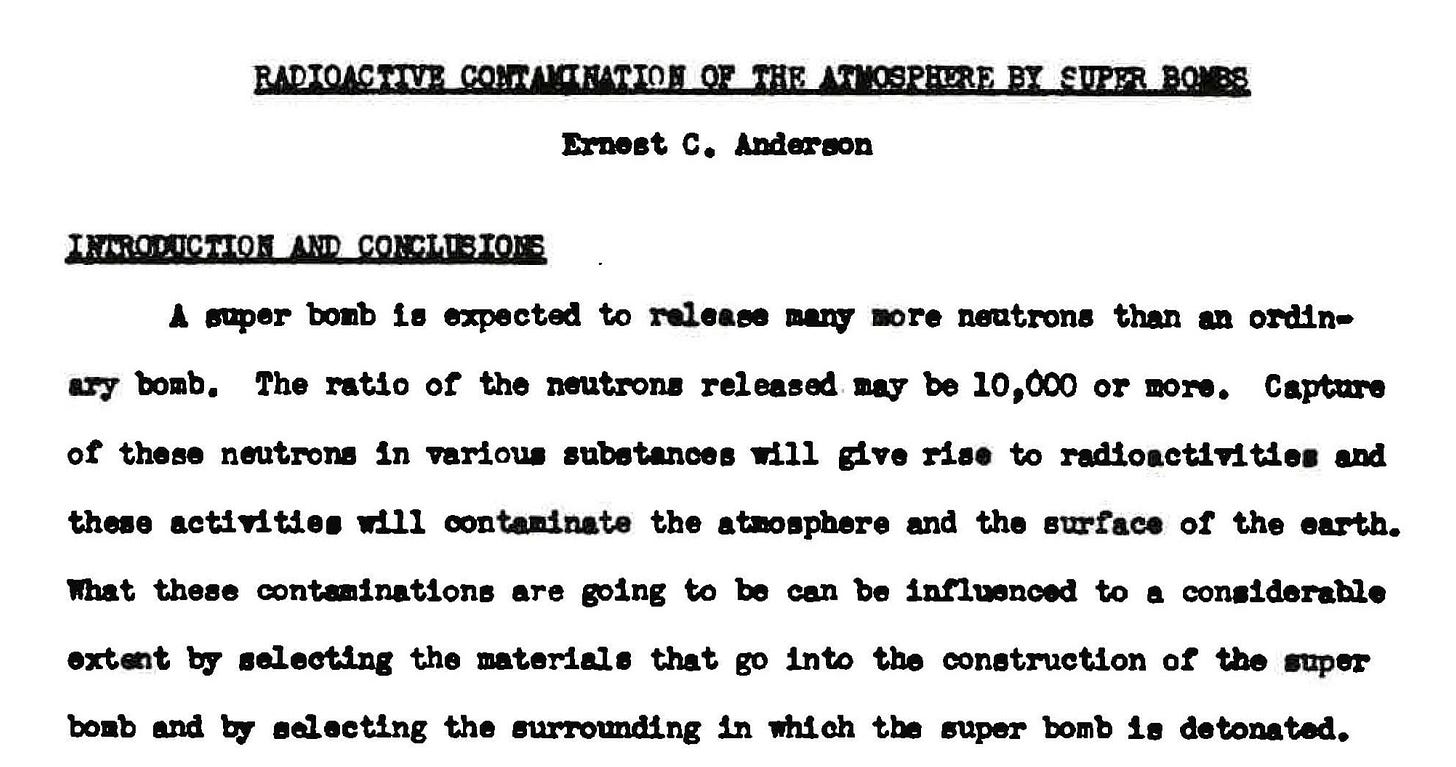

The Manhattan Project History section from 1947, incidentally, argued that perhaps only 10 to 100 Supers would need to be detonated to reach an equivalent radioactivity to 10,000 – 100,000 Nagasaki style bombs. It assumed that these Super bombs would be around 10 megatons in power, but get a substantial fraction (it does not specify, but it is implied a lot) of its output from fission. It optimistically suggests that “presumably Supers of this type would not be used in warfare for just this reason.”

So what does this all add up to? It is interesting that these estimates from 1947 and 1949 both somewhat hover around the same idea, which is that these kind of back-of-the-envelope models imply that it is pretty difficult to contaminate every square inch of the Earth with a lethal amount of radioactivity. Which is all very true. Later work would continue on this topic in the 1950s as the (extraordinarily euphemistically named) Project SUNSHINE of the Atomic Energy Commission and the RAND Corporation, which had been pushed by Libby as a result of the development of working H-bombs in 1952, and new concerns about fallout. They too would conclude that it would take much more than tens of thousands of megatons to make the entire world uninhabited from a radioactive point of view.

The more depressing reality, of course, is that you don’t have to uniformly raise the background radioactivity to such high rates for nuclear war to destroy nations, and even civilization itself. But these documents do give some insights into how the existential threat of nuclear weapons was being conceived of by scientists at a time when the arsenals were still quite small compare to what they would become.

Reines was, among other things, a graduate of the Stevens Institute of Technology, and a future Nobel Prize winner (in that order, technically).

F. Reines, “Radioactive Pollution of the Earth’s Atmosphere,” LAMS-542 (March 25, 1947). I have been receiving the fruits of more FOIA requests lately than ever before — this one was for a request filed 2 years ago. The Department of Energy has also recently sent out guidelines requiring everyone who has been waiting for FOIA requests to be processed to reaffirm (with the exact identification numbers for each request) their interest in them. My guess is that these agencies may have had pressure on them to clear the backlog, and are doing it by some means fair (actually processing them) and some means that I consider rather foul (essentially declaring bankruptcy on their overdue requests). But it could be a coincidence.

Reines notes, in his footnote 2, that “Induced activities in naturally present or intentionally placed surrounding media are neglected as are β rays and the effects of Pu. These neglections probably do not alter the results by a factor of two.” In laymen’s terms, he is saying that looking at the gamma emissions of fission products only, and not even the beta emissions of them, or materials made artificially radioactive by the detonation of the bomb, or the un-fissioned bomb fuel itself, is sufficient to get the results he cares about. Adding the others in would both complicate the equation and would not likely result in an outcome that was twice as high as before. I will note that one of the most strangely persistent Internet misconceptions is that fallout intensity is mostly about induced activity or un-fissioned bomb fuel, when all of the literature on fallout modeling almost entirely neglects both of these in favor of a focus on fission products, which are far more intense.

I thank Carey Sublette for this observation, among several others that informed this post. To reach a dose of 500 R, it would require 4.5 million Nagasaki bombs, or 90,000 megatons.

Manhattan District History, Book VIII (Los Alamos Project), Volume 2 (Technical), Rev. Date 29 April 1947, on XIII-9 and XIII-10.

Ernest C. Anderson, “Radioactive Contamination of the Atmosphere by Super Bombs,” LAMS-983 (29 November 1949).

![“The most world-wide destruction could come from radioactive poisons. It has been estimated that the detonation of 10,000–100,000 fission bombs would bring the radioactive content of the Earth’s atmosphere to a dangerously high level. If a Super was designed with a U-238 [deleted word — blanket?] catch its neutrons and add fission-energy to that of the thermonuclear reaction, it would require only in the neighborhood of 10 to 100 Supers of this type to produce an equivalent atmospheric radioactivity. Presumably Supers of this type would not be used in warfare for just this reason.” “The most world-wide destruction could come from radioactive poisons. It has been estimated that the detonation of 10,000–100,000 fission bombs would bring the radioactive content of the Earth’s atmosphere to a dangerously high level. If a Super was designed with a U-238 [deleted word — blanket?] catch its neutrons and add fission-energy to that of the thermonuclear reaction, it would require only in the neighborhood of 10 to 100 Supers of this type to produce an equivalent atmospheric radioactivity. Presumably Supers of this type would not be used in warfare for just this reason.”](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!wI4e!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4ae84472-e527-46d0-a944-9c6a8b2f21a5_1896x786.jpeg)

I suppose it’s too strong to imagine decision makers reading such reports and concluding that we can keep growing our arsenals because even if we used all we had at the time we wouldn’t poison everyone. But what else could motivate such calculations? Then there is the matter of fires caused by nuclear weapons. A parallel calculation could determine how few nuclear detonations would be required to generate firestorms sufficient to diminish agricultural productivity to the point where human civilization becomes unsustainable. The latter number might well be smaller than the former number. (Kudos to Lynn Eden, naturally).

The hypotheticals make me think of the massive amount of research on actual nuclear weapons tests' health effects, where radiation from any given test could, under some conditions, spread as far as 1000 miles. Given the high number and diverse locations of tests over the years, this has had implications globally in terms of cancers caused. These are mostly US-related links, but there are similar findings for French tests. https://ia800508.us.archive.org/9/items/NuclearWeaponsTestsAndCancerRisks/Nuclear%20Weapons%20Tests%20and%20Cancer%20Risks.pdf, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation/i131-report-and-appendix, https://www.anbex.com/nuclear-weapons-fallout/, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)61037-6/abstract.