"Launching missiles is your job."

The sublime banality of Frederick Wiseman's "Missile" (1988)

The documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman (1930-2026) died last week, at the age of 96. Wiseman’s films were arguably an esoteric taste, staples of art-house theaters, film school courses, and discussions about filmmaking as an ethnographic practice. Wiseman’s career was prodigious, and he directed nearly a film a year between 1967 and 2023 — 48 films in 56 years.

Wiseman’s documentaries are essentially a genre unto themselves, a fly-on-the-wall approach to institutional ethnography. Wiseman’s subjects are all social organizations, institutions, or spaces of widely varying types, and the titles are typically spare and descriptive: High School (1968), Hospital (1970), Juvenile Court (1973), Racetrack (1985), Central Park (1990), Boxing Gym (2010). Some of them are even more simple and declarative, such as Primate (1975), which focused on the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, or Meat (1976), about a slaughterhouse.1

Wiseman’s films typically eschew any added soundtrack, informative text overlays, or obvious “plot.” Somehow, over many, many decades, he talked himself and his crew into these often quite sensitive places and was allowed to just film, film, and film. Out of vast amounts quantities of filming — hundreds of hours per film, probably — the people who he films appear to just forget he is there, and he then edits the eventual footage into what could be described as a profile of his institutional subject.

They are not, of course, truly narrative-free. The films always tell some kind of “story,” although not often one with any kind of clear narrative resolution. They always tell you something about the kind of people who come together in whatever place he is profiling. Wiseman doesn’t tell you how a hospital works in Hospital, for example, but he shows you the kinds of spaces that hospitals are: collisions between people of all walks of life, under circumstances both mundane and exceptional. The identities of the characters in his film are usually unclear except in their relationship to others: the teacher and the student, the doctor and the patient, the researcher and the monkey.

Wiseman’s films can have an illusion of unvarnished objectivity, although Wiseman was clear that this was truly just an illusion:

What you choose to shoot, the way you shoot it, the way you edit it and the way you structure it... all of those things... represent subjective choices that you have to make. … The compression within a sequence represents choice and then the way the sequences are arranged in relationship to the other represents choice. All aspects of documentary filmmaking involve choice and are therefore manipulative. … I think what I do is make movies that are not accurate in any objective sense, but accurate in the sense that I think they’re a fair account of the experience I’ve had in making the movie.

One of Wiseman’s least-heralded films, in my experience, is one that came out in 1988 with the simple title Missile. Missile is about the training of Minuteman launch officers at Vandenberg Air Force Base, and appears to have been filmed in 1986 (at the end there is a reference to the recent Challenger accident). It is exceedingly rare to get this kind of “access” to missileer training, and over time it has also no doubt become something of a time capsule of that particular Cold War moment.

Like most of Wiseman’s films, Missile is interesting in what it shows, but the act of watching it is one of incredible boredom, and requires considerable patience. The film begins with what feels like the first class in a 14-week training sequence, and these classes are not meant to be exciting. Missiles are not meant to be exciting: if working in a nuclear weapons facility is exciting then something has probably gone very wrong. The boredom of it all is contrasted with the “awesomeness of this responsibility,” as the first instructor puts it, of the task at hand: being the ones who would, if called upon it, be turning the keys that launched thermonuclear-tipped ICBMs.2

The first 20 minutes of the film are just this class, in fact, and the focus of the class is on the ethics of the US nuclear weapons system. It is a meandering discussion, with the instructor asking the students what they knew about the My Lai massacre, and about the Nuremberg trials and the “just following orders” defense. The students were aware of these things, but the instructor never really (at least in Wiseman’s showing) hammered home any particular conclusion about them. If anything, he seemed to defend aspects of My Lai, emphasizing the civilian-appearance of the Viet Cong.

So what does it all add up to? The instructor never really resolves any of the ethical or even legal questions on film, other than to be very clear that while they do not want their launch officers to be “robots” (a word he pronounces almost like “ribbits,” an accent affectation that fiction could never capture), they also do not want any launch officers having any kind of second thoughts before they take the role. Anyone who has the slightest doubt, or ethical or moral hesitation, about following through on a properly-authenticated Emergency War Order (EWO, pronounced ee-woe), is explicitly told to leave before they waste too much of everyone's time.

Which is a bit awkward. One student — one of the few women — offers up the notion that the mere presence of the missiles deters nuclear war, and that this makes the mission a moral one. The instructor doesn’t really appear to take her up on this with much enthusiasm, even though it is a standard line about these jobs.

Perhaps he understands why this doesn’t really solve the issue he’s posing: the moral/ethical question is not would you accept maintaining deterrence, the moral/ethical question is, if deterrence fails, would you follow an order that could result in the deaths of millions of civilians. Which is to say, deterrence can perhaps create the moral “cover” for doing nuclear-weapons related work… but if you’re actually going to be turning those keys, you need a bit more than that to fall back on.

Or perhaps he doesn't care all that much. Because the goal does not appear to give the candidates that kind of moral absolution. Rather, the goal of this moral discussion appears — to me at least — to be about weeding out anyone who will be a problem. Which is to say that the goal doesn’t appear to create rigorous moral or ethical justification for actually turning the launch keys, but to simply make sure that nobody who is proceeding with the training actually requires that kind of justification.

Which is not necessarily a critique, although bringing up this issue in the context of My Lai and Nuremberg lends itself to a certain kind of critique, and that seems to be Wiseman’s point. The entire training, and its Southern California setting (which Wiseman occasionally shows us), is, well, banal. It’s not necessarily the banality of evil, but it’s banal nonetheless. There are a few high-level discussions about things like ethics, the domestic legal authority for using nuclear weapons, and even the goal of nuclear deterrence, but for the most part this feels tacked-on to the main part of the training, which is about technical procedures for making sure the missiles are ready to launch at all times, and then launching them when ordered to do so.

What is the mission of the Minuteman missile system? An instructor asks the candidates this question, and they dutifully refer to a manual in front of them where they read:

The mission of the Minuteman hardened and dispersed weapon system is to deliver thermonuclear warheads against strategic targets from hardened underground launchers in the continental United States.3

That’s the mission. Not deterrence. Not preserving freedom. Those things, to the degree that they are at play at all, are the more abstract justifications for the system. The system itself is an immensely complex sociotechnological arrangement of materials, electronics, regulations, and, at the heart of it, people. It is mundane, it is banal, it is tangible. This is what Wiseman is showing us — the banality of deterrence, perhaps.

And of course, as with all instruction, there is a bit of banter and humor, even about grim topics. Some of the candidates have previously worked with liquid-fueled Titan II missiles, and one of the instructors joked about how much easier the maintain the solid-fuel Minuteman missiles are:

Titan is, in a word, a volatile system. You drop a wrench, you can launch a missile — something like that. No, I’m just kidding.

He smiles and raises his eyebrows, and we can tell he’s only somewhat kidding. (In 1980, a dropped wrench set off a chain of events in a Titan II silo in Damascus, Arkansas, which resulted in the missile fuel detonating, ejecting its thermonuclear warhead, and killing one officer. Perhaps the influx of Titan candidates is because they began to decommission Titan II bases after that.)

As one of the instructors tells the candidates, the classroom work is abstract, and the real learning, and telling who has learned, takes place inside the simulated Launch Control Center where the candidates will drill on both the day-to-day aspects of being a missileer and the act that will hopefully never occur — the launch of the missile. Wiseman’s crew is allowed to see this in some detail, and we watch various candidates stumble through the procedures with varying degrees of confidence, observed all the while. “When you get into the EWO [Emergency War Order] part of the mission, that’s the job,” one observer lectures them. “Launching missiles is your job.”

Wiseman tacks between the classroom, the simulator, and the even more truly mundane activities on the base — a cookout and a softball game. The classroom is where abstract discussions take place about the nature of nuclear war. Like all people who work with these things on a daily basis (myself included) they lapse into an easy familiarity with horrible ideas. The ethical and legal issues appear to be reserved exclusively for day one, and further talk becomes about “the job” and is lack of individual responsibility to do anything other than to launch the missiles if asked to. As one instructor puts it:

The thing you want to do is get your [launch] key turn in when you’re supposed to. And to do that, it needs to be very rudimentized [sic], very structured, you don’t want to let anything bother you, just get the task done, and leave it at that. Get a successful launch and take care of any other problems that happen afterwards.

There is a lot of discussion, both in the classroom and in meetings between instructors (which, again, somehow Wiseman had access to) about making sure that weak candidates are either rejected or improved. We get to see one instructor giving a candidate test-taking strategies. If you have four options and don’t know which one is correct, choose the longest one, it is usually correct. If you have four numerical values and don’t have a clue which one it is, throw out the extremes and guess between the remaining ones. Perhaps these are decent test-taking strategies, but it feels a bit insane to imagine telling someone good strategies for guessing on a test about nuclear weapons use.

Wiseman’s eye is clearly drawn to the presence of women in the training, and the fact that it appears to be a novelty; some of the classes look like women make up roughly 25% or so of those present, while some seem to have none. All of the instructors and senior officers appear to be male. In one discussion, apparently with all men, the issue of “fraternization” is raised, with male candidates warned that while they do not need to shun friendship and camaraderie with the women, they should make sure that, “just don’t get it to the point where people start thinking that something’s going on.” In another class, where everyone appears to have put in for assignment at Whiteman Air Force Base (Missouri), the women there make the point that Whiteman was at that time the only Minuteman base that had women launch officers.

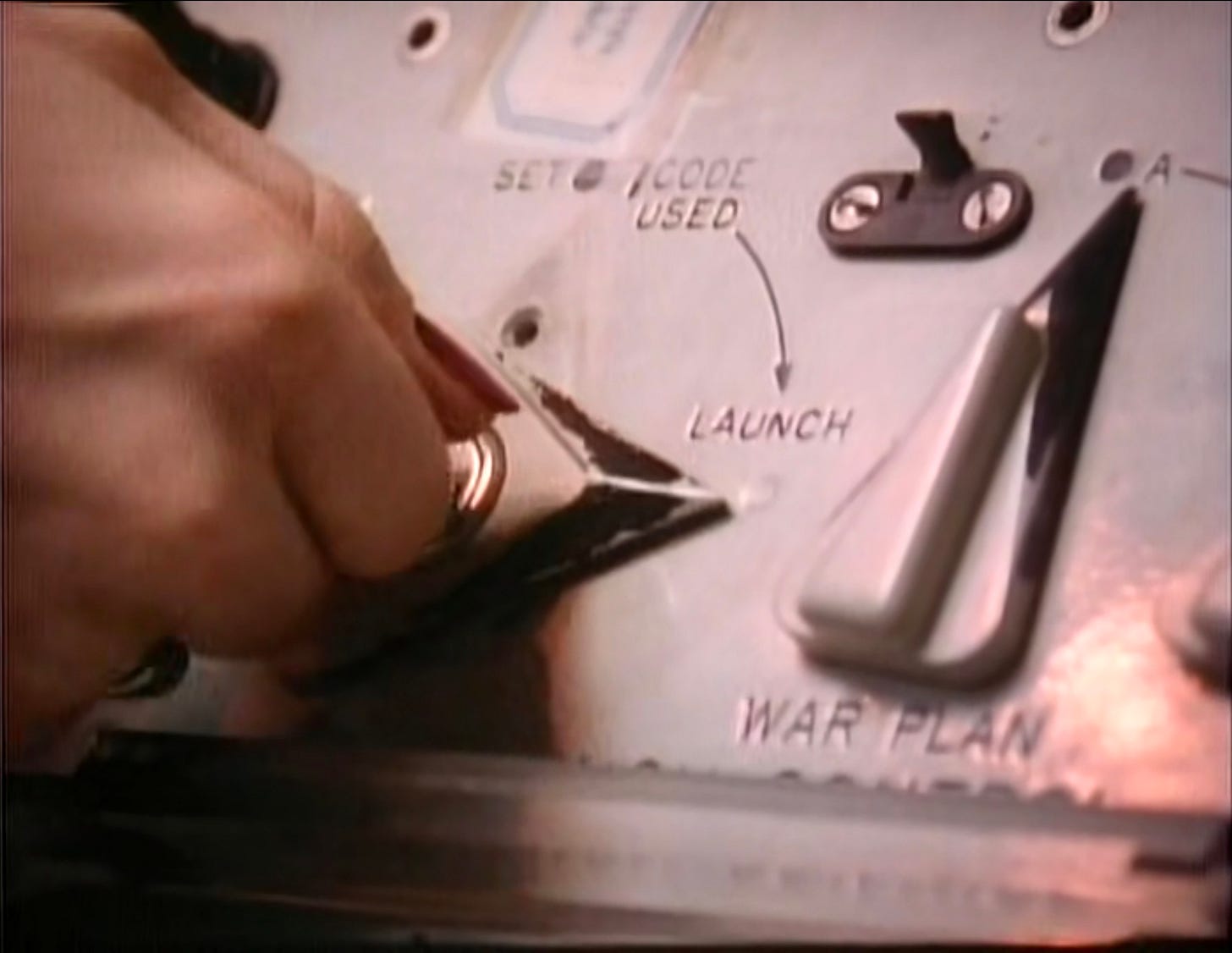

One of the final sequences in Missile is of two women candidates running through a full simulation of an Emergency War Order, launching the ten (simulated) Minuteman missiles assigned to them. The women do a great job; they have studied the procedure, they know what they are doing, even if it is clear they are still new at this (they both attempt to put the launch keys in upside down the first time, for example, but quickly resolve the issue). They are efficient, working together to prove, to anyone who might doubt, that they would be perfectly capable of fighting a nuclear war if called upon to do so.

Is Missile a good film? Yes. Is it an important film? Yes — everyone seriously interested in nuclear weapons ought to see it, in my mind, because it gives an insight into these “people of the bomb” that is otherwise hard to capture, and informs common questions even today like, “would the launch officers carry out nuclear launch orders under any circumstances?” (Answer: probably; that is plainly a large part of what they were selected for.)

Is Missile fun to watch? No. It’s boring. And that’s the point. It makes perfect sense that films about nuclear weapons that are trying to capture the interests of a disinterested public are often thrillers, but the everyday reality is just… reality. It’s just another facet of life. The part that’s not normal is that these activities, if taken down certain roads, lead to the death of thousands, millions, even possibly billions. It’s the juxtaposition, between the tedious checklists and acronyms on the one hand, and those terrible possible futures on the other, that makes everything about nuclear war feel a little surreal.

Wiseman’s Missile captures these juxtapositions beautifully. The best shot, for my money, is the one (above) of a female candidate turning her launch key in the simulator. It is a portentous image: if this had been a real launch, some 30 nuclear warheads would now be on their way to the Soviet Union, each capable of releasing around 20 times the energy as the Hiroshima bomb. Wiseman is zoomed in on her hand as she turns the key, and we can see her red nail polish, a very different kind of signifier. After the indicators signal that the missiles are out, and her job is completed, she concludes dutifully: “And that’s it. That’s all she wrote.”

Wiseman’s films are often available on Kanopy (often accessible for free through a public library account in the USA). “Missile” is available (for me, anyway) here. My screenshots are from a DVD rip I did of it, having purchased a copy for teaching with many years ago, and are about the same quality as the ones on Kanopy.

When I toured the Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant (New Hampshire) a decade ago, there was a clear emphasis on how boring it was to work there, because boredom was a sign of control and predictability. While there, I was told by someone that in fact the biggest security problems they faced in some kind of audit was the fact that the security forces would fall asleep. As a result, they changed how they deployed them, so that the boredom would not be totalizing, and had them do things like simulate how they would attack or defense the plant against terrorists. While I was touring, they were doing one of those simulations, and so as we walked between buildings we would sometimes see security forces pretending to shoot one another. It was fairly surreal.

“Dispersed” in this context means that each Launch Control Center is physically separate (3 nautical miles away at least) from its missiles, and each has launch authority over 10 Minuteman missiles (another site must also concur with the launch request, which requires two officers in any given LCC to issue). Each missile can carry up to 3 independently-targetable re-entry vehicles.

I grasped that *boring is good* back about the time this was filmed. About the same time I qualified MCCSUP and was suddenly The Guy. Not Boring meant something was happening, usually bad.* And when stuff goes wrong, it's The Guy who has to make decisions and who is held accountable for them afterwards. (And if it's bad enough, the Old Man takes an interest, and that's never fun.)

As I've said elsewhere, I soon learned to appreciate boring like it was a lovely single malt.

I don't recall our training (at the enlisted level) ever going into morality... But whatever the official line, at the deckplate it was an article of faith that our job was deterrence. That if we ever had to launch, we'd failed. I don't have any idea about officer training.

* And an LCC crew doesn't face nearly the same range of challenges that an MCC watch section does...

I just found this movie on Kanopy - it’s a listed ‘learning resource’ on my library’s website - right below JSTOR…who knew?

Thoughts:

It always blows my mind how many people involved in weapons and power generation pronounce it ‘new-cue-ler’ (have *I* been saying it wrong all these years?)

Along the same lines I learned NATO phonetic ‘papa’ is pronounced papá…oh, and S is written with a vertical stripe (like pesos!), and a 1 has a horizontal line under it. Are these the rules of writing with a grease pen?

It’s certainly a little slow in spots to be sure…but the overheard conversations provide occasional nuggets - nuke and otherwise (eg the guy talking about scavenging around Battle of the Bulge sites…he found a paratrooper helmet!?)

For people old enough to have clear memories of January 1986 - it’s a fun time capsule on hair, clothes, glasses styles, slang/expressions, etc.

(Most video of the 80’s provide just a rough time-parallel for me “oh I would have been in 8th grade” - but because of the Challenger tie in, I remember very specific things I would have been doing/saying/thinking that very week.)

On the banality of deterrence thing…

It seems like one goal of missileer training is once you weed people out who are too focused on the moral implications of launching, you bury people in procedure and repetition to disconnect the checklists and status lights from the missiles…make them forget all about what those keys are connected to. That way you don’t end up with any John Spencer (er…Leo McGarry?) moments at go time.

I found it interesting that when the two women graduate, the instructor tells them the Minuteman is so trouble-free, it’s easy to get complacent. Probably a little like flight training vs actual flying.

I used to wonder about all the effort that goes into drills and training and exacting detail and process around nuclear deterrence… But as this movie makes clear - just having the weapons isn’t enough. You have to demonstrate to your adversary that they are available, reliable, usable, and the people who operate them can and will do so…