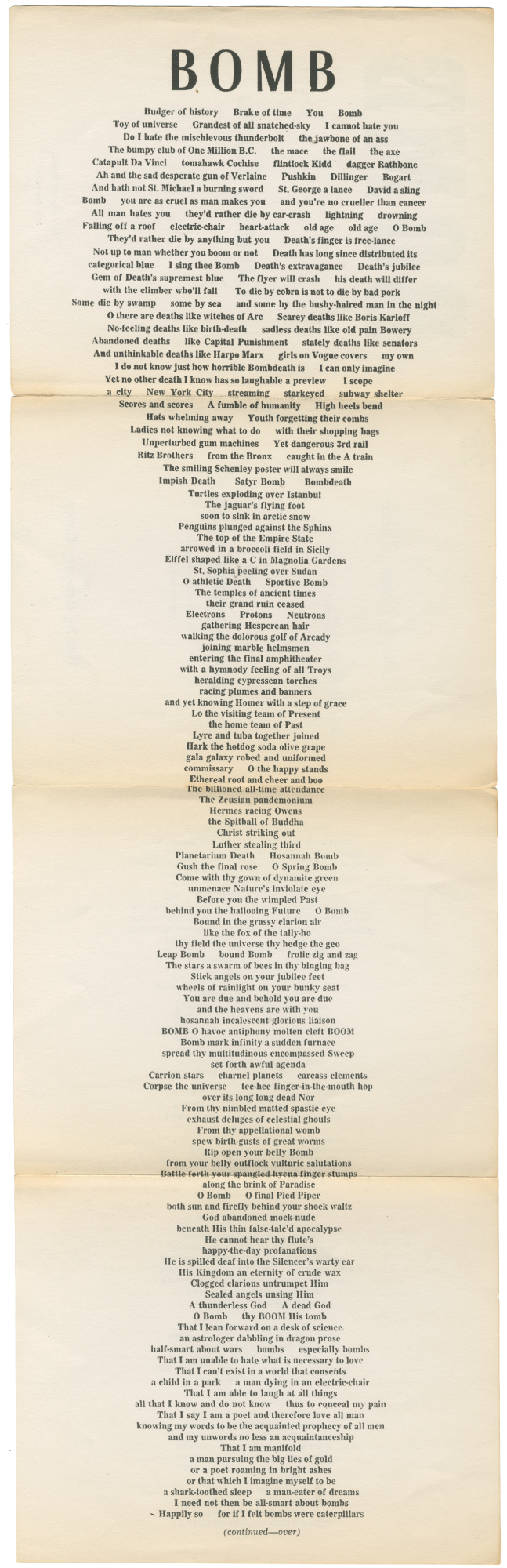

In 1958, the famed City Lights Books published Beat poet Gregory Corso’s poem “BOMB” as a provocative broadside. It is a long, curious, gnomic digression on, or deconstruction of, what it means to live in the megaton-and-missile age. The broadside unfolds vertically, as a mushroom cloud’s “head” and “stem”:

This page contains it retyped with the appropriate spacing. And if you want to hear Corso read it aloud, here you go:

My own sense is that it starts out strong and then becomes perhaps a bit too associative for my tastes. The mushroom head starts out boldy:

Budger of history Brake of time You Bomb

Toy of universe Grandest of all snatched sky I cannot hate youAnd there’s a really smart section that faces whether death-by-bomb is so different than any other death in this world (apologies that the formatting is not quite capable of being preserved):

Bomb you are as cruel as man makes you and you're no crueller than cancer

All Man hates you they'd rather die by car-crash lightning drowning

Falling off a roof electric-chair heart-attack old age old age O Bomb

They'd rather die by anything but youOnce you get further down the “stem” of it, it becomes a little less clear to me what’s going on. A poem is not merely a means of conveying ideas or a “message,” of course, and I can respect a strong turn of phrase. But I’m not really sure this works as well as the above:

Oppenheimer is seated

in the dark pocket of Light

Fermi is dry in Death's Mozambique

Einstein his mythmouth

a barnacled wreath on the moon-squid's headAnd it does resort to perhaps a bit too much of the, err, “BING BANG BONG BOOM” towards the end:

O resound thy tanky knees

BOOM BOOM BOOM BOOM BOOM

BOOM ye skies and BOOM ye suns

BOOM BOOM ye moons ye stars BOOM

nights ye BOOM ye days ye BOOM

BOOM BOOM ye winds ye clouds ye rains

go BANG ye lakes ye oceans BING

Barracuda BOOM and cougar BOOM

Ubangi BOOM orangutang

BING BANG BONG BOOM bee bear baboon

ye BANG ye BONG ye BINGI’m not an expert on the Beats, but I gather this sort of thing was bold in the 1950s, so I will give it due credit as a historical artifact while not finding it quite so compelling today…

It does have one really good line at the end though:

that in the hearts of men to come more bombs will be bornI’m not a poet nor much of a reader of poetry, but I have a lot of respect for that ability to craft a strong, resonant, powerful line. “In the hearts of men to come, more bombs will be born” works for me. “BING BANG BONG BOOM,” uh, doesn’t.

There are a lot of commentaries on “BOMB” over the years, and even at least one graduate thesis dedicated exclusively to it. The reception to the poem has been mixed — some heralding it as one of the great Beat offerings, some deriding it as fairly silly. A reviewer at Time magazine referred to it as “Beat blather,” which feels like one of those opinions that doesn’t age well. I find some Beat poetry very moving, and some parts of “BOMB” are great, even if a lot of it does very little for me.

There is a story that when it was read to a poetry group at Oxford, they disapproved of it. Many of the quotes about this reading say that shoes were thrown, although a later commentary from someone in attendance suggests this is an exaggeration, that the sentiment was rather that: “We thought it a lousy poem, but we threw no shoes.”

In 1981, Corso would call back to “BOMB” in his short poem, “Many Have Fallen”:

In 1958 I took to prophecy

the heaviest kind: Doomsday

It was announced in a frolicy poem called BOMB

and concluded like this:

Know that in the hearts of men to come

more bombs will be born

. . . yea, into our lives a bomb shall fallWell, 20 years later

not one but 86 bombs, A-Bombs, have fallen

We bombed Utah, Nevada, New Mexico,

and all survived

. . . until two decades later

when the dead finally died

Which is far less “frolicy” than “BOMB,” and its brevity and focus is, at least for me, more powerful overall, even if it is a sort of grim victory lap to run on one’s career.

Bob Dylan wrote in Chronicles about his experiences with the Beats and “BOMB” in particular as he contemplated exiting from the world of fraternities, jobs, and the straight life:

I suppose what I was looking for was what I read about in On the Road — looking for the great city, looking for the speed, the sound of it, looking for what Allen Ginsberg had called the “hydrogen jukebox world.” Maybe I’d lived in it all my life, I didn’t know, but nobody ever called it that. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, one of the other Beat poets, had called it “The kiss proof world of plastic toilet seats, Tampax and taxis.” That was okay, too, but the Gregory Corso poem “Bomb” was more to the point and touched the spirit of the times better — a wasted world and totally mechanized-a lot of hustle and bustle — a lot of shelves to clean, boxes to stack. I wasn’t going to pin my hopes on that.

…which is high praise, indeed.

I’m not sure “BOMB” does as much for me today, but hey, perhaps it shouldn’t — if something as rooted in its moment like “BOMB” didn’t feel a bit out of date 70 years later, what would that say about it, or us?

The best lines in this poem are far better than pretty much any other poetry from that era, so I can excuse the dreck.

This reminds me of the short story (if you could call it that) "Scratch," by Iain M. Banks. It's a stream-of-consciousness critique/rant/word object attacking Margaret Thatcher's England, with a definite fear-of-nuclear-war aspect. It's so chaotic that I couldn't even read it at first, let alone interpret it, but it's grown on me over the years. The accompanying illustration in the copy I own helps a lot: a mushroom cloud rising over a street with parked cars and a discarded newspaper in the foreground: the infamous "GOTCHA" cover of The Sun from the Falklands War.