Cinéma verité, cinéma mort

How guerrilla filmmaking and the French New Wave gave birth to the modern zombie apocalypse film with Romero's Night of the the Living Dead

Billy Middleton is a professor of creative writing at my university, and a good friend of mine. He’s also a true connoisseur of the horror genre, and as someone who is not very steeped in that world, I asked him to write something about zombie films for Doomsday Machines as the first of what I hope are many guest posts. I’ll be posting something later in the week as well. –A.W.

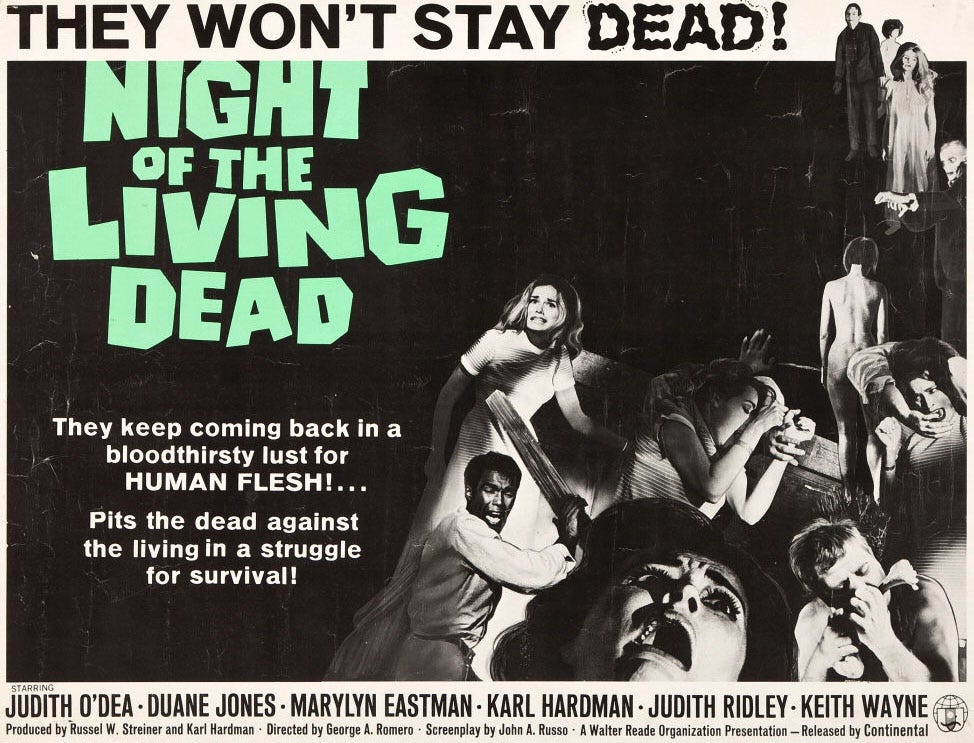

At the time of Night of the Living Dead’s release in 1968,1 most horror movies were children’s entertainment, schlock-fests featuring actors in rubber suits. In a contemporary review , Roger Ebert describes his experience of watching it during a Saturday matinee, in a theatre filled mostly with children:

There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying.2

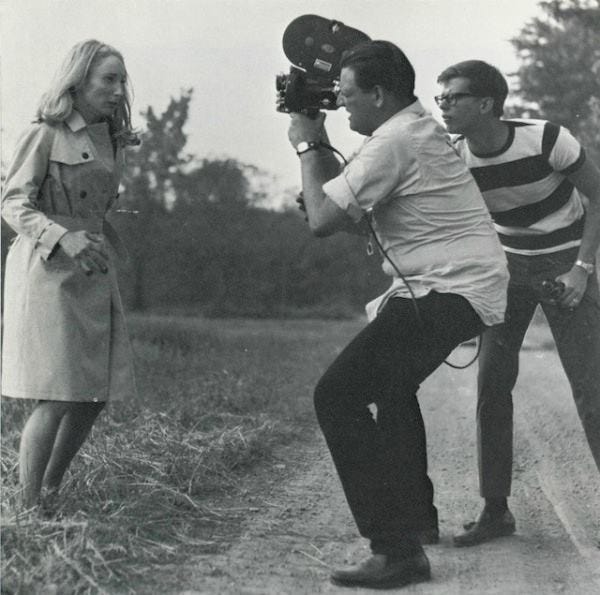

Besides the gore and violence, which were extreme for the time, the film was also terrifying because of how real it felt. This was at least partially because, and not despite, its low budget. Director and producer George A. Romero and his production crew, Image Ten Productions, had just over $100,000 to work with, so they had to resort to guerrilla filmmaking that, in the end, led to a movie that felt rawer, more urgent, and more real.3

Guerrilla filmmaking is a popular approach among indie filmmakers like Romero. As the name suggests, it is a filmmaking style that is fast, cheap, and often a little bit out-of-control. Such films are shot almost entirely on-location rather than in soundstages, and often quickly and sneakily because the filmmakers often lack the proper permits. Props are minimal, and dialogue is often improvised. Cameras are sometimes hidden, or handheld, with various degrees of stability. Every decision is about efficiency: they want to get in, get the movie made, and get out again.

Among the earliest guerrilla filmmakers were the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague), whose indie aesthetic and preference for low budgets and complete artistic control were a central part of their creative ethos. The French New Wave inspired similar movements across the globe, including America, where a new generation of young auteurs, including Romero, were dubbed the New Hollywood.4 The filmmakers of the French New Wave often merged guerrilla tactics with their signature cinéma verité style,5 a logical pairing since cinéma verité values the visual appearance of truth and authenticity above all else, and that generally means less artifice.

Cinéma verité prioritizes real settings over soundstages, nonprofessional over professional actors, handheld camerawork, and a “fly on the wall” approach to cinematography. Inspired by Dziga Vertov’s concept of Kino-Pravda (“film truth”), cinéma verité’s goal is to film with minimal planning or scripting in order to arrive at the core truth of the scene. Though it started as a style specific to documentary films, elements of it quickly spread to fiction films throughout the 1960s, shaping the aesthetics of directors worldwide.

The influence of cinéma verité can be seen all over Night of the Living Dead. Unable to afford soundstages, Romero had no choice but to shoot mostly on-location. The majority of the movie was shot at the Evans City Cemetery, about thirty miles north of Pittsburgh, and a neighboring farmhouse scheduled for demolition, which the filmmakers were able to rent.6 The creepy, abandoned farmhouse out in the middle of nowhere is practically a character itself, and it has a sense of familiarity. It looks like any of a hundred rundown old farmhouses you might pass driving down a country road.

The dialogue, largely improvised, also contributes to the sense of authenticity. In one scene, Ben, our leading man (played by Duane Jones), describes for our leading lady, Babara (Judith O’Dea), a zombie attack at Beekman’s Diner:

…a big gasoline truck came screaming right across the road. But there must have been ten, fifteen of those things chasing after it, grabbing and holding on. Now, I didn’t see them at first. I could just see that the truck was moving in a funny way. Those things are catching up to it. The truck went right across the road. Slammed on my brakes to keep from hitting it myself. Went right through the guardrail. I guess, I guess the driver must have cut off the road into that gas station by Beekman’s Diner. It went right through the billboard, ripped over a gas pump and never stopped moving. By now it was like a moving bonfire. Didn’t know if the truck was going to explode or what. I can still hear the man screaming. These things just backing away from it. I looked back at the diner to see if there was anyone there who could help me. That was when I noticed that the entire place had been encircled, wasn’t a sign of life left except… By now there were no more screams. I realized that I was alone with fifty or sixty of those things just standing there, staring at me. I started to drive, I just plowed right through them. They didn’t move. They didn’t run or… just stood there, staring at me.

Ben’s story is the scene, as there was no way they could’ve afforded to actually film what Ben describes. But it works. The shellshocked manner in which he describes it feels so genuine that his story is more frightening than the actual scene would’ve been, and it lets the audience’s imagination do the dirty work. In reference to this particular scene, Judith O’Dea later recounted: “I don't know if there was an actual working script! We would go over what basically had to be done, then just did it the way we each felt it should be done.”7

Ben’s entire character was, in fact, a product of improvisation. The original description of the character was not much more than an angry, unpleasant truck driver. No mention was made of his race, but when Jones, a Black man, delivered the best audition and became the clear choice for the role, Romero and his co-producers, John Russo and Russell Streiner, decided to keep everything about the character exactly the same. As Romero has described in interviews, they thought they were being cool by playing it entirely “colorblind.” But Jones had concerns, and he pushed back by improvising much of his dialogue to make Ben sound more thoughtful and intelligent, though still pretty angry, and a narrative begins to emerge: Ben’s anger stems from the fact that his capabilities are overlooked due to his skin color.8

Though Romero, Russo, and Streiner initially wanted to keep the racial commentary relegated to subtext, the social context of the time made that impossible. The film was shot between July 1967 and January 1968, in the wake of the Detroit and Newark race riots. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., that April, was still a raw and palpable event when the film was first filmed in early October. In this context, it was, and is still today, impossible not to view Ben’s conflict with his fellow survivor, a white man named Harry Cooper; nor his death at the hands of a redneck posse who “mistake” him for a zombie outside of a racial lens.9

Eventually, the producers embraced the racial politics of their movie, and thus another central trope of the zombie apocalypse genre was established: zombie as sociopolitical commentary. Night of the Living Dead reflected late-sixties anxieties about race and Vietnam; its sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), set in a shopping mall, was an unsubtle allegory for mindless consumerism; and the third entry in the initial trilogy, Day of the Dead (1985), explored Reagan-era warmongering and distrust of the military.

Beyond writing, acting, and setting, we can also see the influence of cinema verité in Romero’s cinematographic choices. The movie extensively featured handheld camerawork, such as a scene early on where Barbara escapes a zombie in the cemetery that has just killed her brother Johnny. She scrambles up a steep hill and onto a gravel road, and Romero’s shaky, handheld camera backpedals away from her, fixating on Barbara as she desperately flails towards it.

There is also a lot of “fly on the wall” cinematography. In another scene, the camera is placed unobtrusively in the corner of an upstairs hallway to observe Ben wrapping a devoured corpse in a rug for disposal. The camera is tilted on its x-axis in this shot, in what is referred to as a “Dutch angle,” to create a sense of voyeuristic tension in the viewer: we’re not supposed to be seeing this.

Another cinematographic choice that film historians and scholars have frequently remarked on is Romero’s use of 35mm black-and-white film stock over color. Romero made this choice for a variety of reasons, but mainly he hoped that filming in black-and-white would cover a lot of the rough edges resulting from his lack of experience at making a feature length film.10

It also allowed for the minimal use of props, special effects, and makeup. Bosco Chocolate Syrup (the same brand Hitchcock used for Psycho eight years earlier) served as blood, and the human flesh the zombies eat was boiled ham and offal donated by an investor who owned a butcher shop.

For the zombies, makeup artist Marilyn Eastman (who also played Helen Cooper), only needed to use some pale paint with dark circles around the eyes, and mortician’s wax for their open wounds. The use of black and white also allowed the filmmakers to rely on a chiaroscuro lighting style to emphasize the characters’ growing sense of dread and isolation.

A side-effect of the use of black-and-white film stock was that it served as a nod to documentary realism. As Stephen Harper has noted, news broadcasts in 1968, especially in rural markets, would’ve likely still been broadcast in black-and-white.11 As such, the overall context of the film’s aesthetic choices add to its sense of unsettling “reality.” Its in-film news broadcasts in particular serve to reinforce this while providing backstory to the viewer about how the zombie apocalypse works in a way that seems grounded within both the movie’s cinematic world, and the visual culture of the contemporary audience.12

After shooting was completed, Romero and his collaborators initially struggled to find a distributor. Some were turned off by the violence and gore, others by the use of black-and-white film stock. Everyone wanted them to reshoot the ending to be a happier one, a change the filmmakers were unwilling to make.

Eventually, the Walter Reade Organization agreed to show the uncensored, unedited film, but the title the crew had settled upon, Night of the Flesh Eaters, had to be changed due to similarity with another film. Thus, it became Night of the Living Dead. However, the copyright notice was infamously left off the title card of the film, thereby landing it in the public domain, causing the cast and crew to lose out on all future revenue and leading to dozens of unsanctioned rereleases, special editions, and remakes, many of which were terrible enough to leave a stain on the original’s reputation.13

The initial October 1968 screening of the film took place in Pittsburgh’s Fulton Theater. Early reviews echoed Ebert’s in their focus on the violence and gore, some going so far as to label the film as a moral failure of the filmmakers. One of the few and first positive contemporary reviews ran in Andy Warhol’s Inter/view magazine. The reviewer, George Abagnalo, declared that Night of the Living Dead “should open at an art house and run for at least a month, because it is a work of art.”14 Though a minority opinion at the time, Abagnalo has been proven correct.

The film has appeared in numerous best of all time lists, and the Library of Congress has added it to the National Film Registry as a film that is “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” After the film received international distribution, the highly respected French journals Positif and Cahiers Du Cinema (where many of the French New Wave auteurs began their film careers as critics) wrote positive reviews, and a 1970 screening at the Museum of Modern Art prompted critical reevaluation. Pauline Kael wrote a backhandedly positive review emphasizing the film’s low budget and DIY aesthetic: “The film’s grainy, banal seriousness works for it—gives it a crude realism; even the flatness of the amateurish acting and the unfunny attempts at campy comedy add, somehow, to the horror—there’s no art to transmute the ghoulishness.”15

The film’s domestic gross of $12 million and international gross of $18 million amounted to a profit of 250 times its $114,000 budget, making it one of the most successful independent films and horror films of all time. Audiences (and some critics) clearly found allure in the film’s controversy and violence, as well as its cinéma verité-influenced sense of “realism. “

Its success spawned a franchise that has since produced five more films. With the exception of Dawn of the Dead (1978), which some critics consider Romero’s masterpiece, none of these sequels have managed to garner anywhere near the success or critical respect of the original. These films’ larger budgets, and more carefully controlled production processes, may have diminished the sense of urgency that made the original so terrifying to audiences. Additionally, gore and violence became more and more common in American film, horror and otherwise, over the following decades, making later films in the franchise less shocking by default. It wasn’t until the release of Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later in 2002 that the zombie apocalypse genre recaptured its magic, largely because that film returned to the grainy, DIY aesthetic re-popularized by indie films of the late nineties and early 2000s.

Had Night of the Living Dead been made under the watchful eye of a studio, or with a larger budget or more forgiving production schedule, Romero and his collaborators possibly would have produced something more polished — but also probably less affecting, less “unexpectedly terrifying,” as Ebert put it. One wonders if we would even have “zombie apocalypse” as a genre had Night of the Living Dead been a bit more traditional, a bit more acceptable, a bit less verité, a bit less willing and likely to make a child cry during a Saturday matinee.

The original script, which at various times was entitled Monster Flick, Night of Anubis, and Night of the Flesh Eaters, centered around a runaway teen who discovers that aliens are harvesting human corpses for consumption.

Ebert later described his January 1969 review as “a review of the audience reaction” rather than a review of the film itself, which he quite admired. This “review” amounted to a tacit endorsement of the new MPAA rating system, which had not yet gone into effect at the time of Night of the Living Dead’s debut.

Image Ten, the production company Romero formed, is named after the ten main members of the cast and crew, who each chipped in $600 to start the company.

Though Romero has tried in interviews to distance himself from the label, it has stuck. Other notable films given the label include Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Mike Nichol’s The Graduate (1967), Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968; one of the other “serious” horror movies of the era), Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), and especially Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), considered by many to be the defining film of the movement.

Edgar Morin coined the term cinéma verité, or “truthful cinema,” to refer to the style he and collaborator Jean Rouch employed in their documentary film Chronicle of a Summer (1961).

One of the few scenes not set in one of these locations takes place in Washington D.C., where a group of reporters surround military and science officials leaving a meeting to pepper them with questions. The crew road-tripped down and hastily filmed near the Capitol Building without the proper permits. In interviews, co-producer Russell Streiner, who also plays Johnny in the film, has quipped that they did this mostly just to make it look like they had a bigger budget since they were filming in multiple cities.

From Jason Paul Collum, Attack of the Killer B’s: Interviews with 20 Cult Film Actresses (McFarland, 2004).

Jones expressed particular concern about a scene in which he strikes a hysterical Barbara to try to bring her back to her senses. Night of the Living Dead was released a little over a year after Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night (1967) had stirred up controversy with a scene in which Sidney Poitier slap a white man.

See also Key and Peele’s “Alien Impostors” sketch for a modern subversion of the trope.

Romero did have quite a bit of experiencing filming commercials, however. He had started his commercial film company, the Latent Image, in the early sixties. They did work for Calgon, Pittsburgh’s local PBS station, and The Mister Rogers Show.

Stephen Harper, “Night of the Living Dead: Reappraising an Undead Classic,” Bright Lights Film Journal (November 1, 2005).

The news broadcasts also establish several of the core tropes of the zombie apocalypse canon: that the recently dead are returning to life to “feast upon the flesh of their victims,” that bodies should be burned immediately to prevent them from returning to life, and that zombies can be killed by “a shot to the head or a heavy blow to the skull.” We also learn that the cause of the outbreak may be radiation from a destroyed probe returning from Venus (a major area of Soviet research interest during the 1960s). This plot point is never explored further in future films in the franchise, however.

US copyright law at the time (until 1978) required an explicit copyright notice for works to be copyrighted. Today, all creative works have an assumed copyright under the conditions of the Berne Convention. The details are complicated. This is not legal advice.

George Abagnalo, “Night of the Living Dead,” Inter/view 1, no. 4 (1969): 23. The review contains some wonderful lines, e.g.: “Some people laugh when the film ends, but not because it is funny or badly done. They laugh because they can't believe what they have seen. Some leave silently, looking as though they're about to vomit.”

Pauline Kael, 5001 Nights at the Movies: A Guide from A to Z (Henry Holt, 1985), 414. Kael’s opening is also amusing: “It would be fun to be able to dismiss [Night of the Living Dead] as undoubtedly the best movie ever made in Pittsburgh, but it also happens to be one of the most gruesomely terrifying movies ever made — and when you leave the theatre you may wish you could forget the whole horrible experience.”