One of the important figures in modern post-apocalyptic imagery is that of the “Prepper” or “Survivalist”: someone who is planning to survive the collapse of civilization by means of taking action today. When I talk to people about Doomsday Machines, this is often the first place their mind goes.

What is a Prepper? Where did the idea come from? When did this kind of behavior start? These are interesting questions for a historian, and I’ve been looking into the matter a bit. I would have thought that there were serious academic studies of it, but my sense is that this is not really the case at the moment. Most of what has been written about the history of this mindset or “movement” has been written either by journalists, by Preppers themselves, or has been done as form of anthropology (studying current Preppers) rather than history.

Journalistic approaches to history can be useful first drafts, but a journalist’s approach is not usually a historian’s approach. “Self-histories” by Preppers are valuable inasmuch as they tell us how they situate themselves into narratives about the past, but they tend to suffer from certain obvious biases (the Prepper histories I have seen, for example, tend to distance their movement from the figures in their movement who have shown themselves to be ultimately noxious over the years, however influential they were at the time). And anthropological studies of Preppers are valuable for understanding the mindset, but don’t tell us about where it came from.

So what I have decided to do is to try and sketch out an outline of “a brief history of Preppers.” This will be a multi-part series (over an unknown amount of time) that pulls together my sense of how the history of this behavior might be understood. It is something I have been thinking about for several years now, and I have been slowly piecing together parts of this. I think understanding the history of Preppers is an important part of understanding the modern post-apocalyptic mindset.

Major caveats: This is not an in-depth study; it is scattershot, and more intellectual history than archival history. These are preliminary categorizations. And it is entirely US-centric; I have not looked at how these ideas have manifested in other countries, or the differences (subtle and not) between US Preppers and other Preppers (or if one wants to even apply the term “Prepper” to non-US movements).

My current plan (subject to change) for this series:

Part 1: Civil Defense and Preppers. Defining our scope of study and talking about the “pre-history” of Preppers. You are here.

Part 2: Retreatism and Survivalism. The emergence of hyper-individualistic survival movements in the late 1960s through the and 1980s.

Part 3: From Survivalists to Preppers. The deeper tarnishing of Survivalism in the late 1990s, and the mainstreaming (and mocking) of individual survival mindsets post-Y2K and 9/11.

Who is a Prepper?

We need to start by defining our terms. The term “Prepper” is a fairly recent one: It doesn’t start appearing as a common term for this kind of behavior until the early 2000s. The show “Doomsday Preppers” (2012-2014) probably helped popularize the term and the idea, although it is clear that the concept predates the show. From the 1970s through the 1990s, the more commonly-used term was “Survivalist” and the movement was called “Survivalism.” My sense is that the terms carry slightly shifted connotations. A “Survivalist” is generally someone participating in or advocating an -ism (Survivalism), which is to say, an apocalyptic ideological conception of the world. “Prepper” can include that, but people can also be somewhat more casual “Preppers” without buying entirely into the mindset of Survivalism. To put it another way, “Prepper” is a more “mainstreamed” idea than Survivalism, a consequence of Y2K fears and 9/11. (I plan to discuss this distinctions and shift at some length Part 3.)

For my purposes, a “Prepper” is someone who believes that the likelihood of social and civilizational collapse is plausible-enough that they believe it is worth time and resources to plan for that eventuality today. Their goal for survival is relatively constrained: they are trying to protect themselves and their families, and perhaps a small subset of other close people, but they are not trying to protect an entire community, nor is their goal to rebuild “society.” It is an individualistic approach to preparedness, and not a collective one, even if, in their pursuit of it, they communicate and share ideas with other like-minded people. The degree to which they engage in a fantasy of post-social existence seems to vary, but I want to make a distinction between people who store a few weeks of food and water in case of a temporary emergency (e.g., a localized national disaster) and people who are expecting a society-wide collapse that could endure for an extended people of time (months to years to forever).

So someone who follows FEMA preparedness guidelines is not necessarily a “Prepper.” FEMA guidelines are not about surviving the apocalypse, and the level of investment required to satisfy those guidelines — although not at all minimal, and I doubt most “non-Preppers” satisfy them (I definitely don’t!) — is much smaller than the level of investment that would be required to survive a prologued social collapse. At the same time, I suspect there are people who align with the “Prepper” mindset who have done essentially no actual “preparation” work other than read about it, and are probably well below FEMA guidelines. So being considered a “Prepper” is about a mindset more than it is about your actual level of “preparation.” We could get into sub-definitional questions (Are Mormons Preppers?) but I think for my purposes this is good-enough to start with.

Preppers and Civil Defense

Prepper-written histories of their “movement” vary quite widely in what they identify as its “pre-history.” Some of them want to draw a real sense of continuity to the deep past: that all human beings prior to the development of modern civilization were “Preppers” in some deep sense, and even in civilized times there have been people, like the American Pioneers, who had to engage in “Prepper” activities as they went “off the grid.” I find this interesting as a work of self-history — an attempt at “normalizing” the mindset, and also one that highlights it deep antipathy to concepts like “civilization” and “society” — but it is not very useful as an historical starting point. Pioneers were not preparing for the collapse of society; their End of the World preparations were more spiritual in nature.

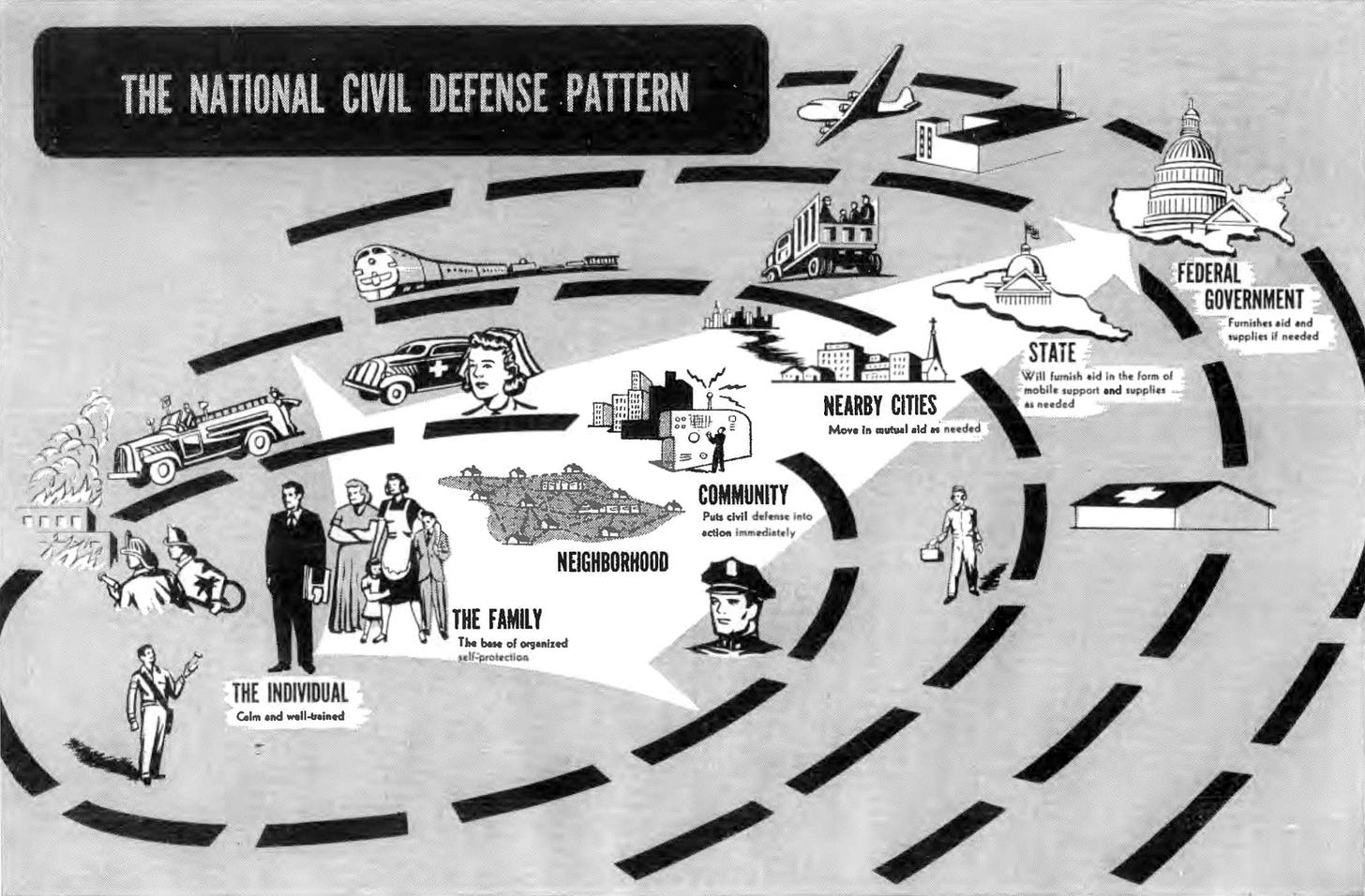

A more sensible place to start is Civil Defense: the various programs run by different agencies of the US government during the Cold War that were designed to mitigate the effects of a nuclear war on American civil society. “American civil society” here is meant to differentiate Civil Defense from other, related concepts, like Continuity of Government, which is about mitigating the effects of such an attack on the American government (e.g., plans to make sure Congress and the office of the Presidency are able to continue in some form), and military defense (e.g., fighter craft trying to shoot down bombers before they reach their targets, civilian or otherwise).1

The Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) was created in late 1950 by President Truman as a result of public and Congressional pressure (he was himself fairly ambivalent about the utility of Civil Defense) in the wake of the detection of the first Soviet nuclear test (September 1949) and the beginning of the Korean War (June 1950). Over the course of the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, its focus was split between trying to organize federal-, state-, and local-level governmental efforts to prepare for nuclear war’s effect on the civilian population (e.g., stockpiling food, water, and medical supplies, and creating organizations and plans for how to organize the post-attack environment) and creating preparation messaging meant for civilians.

It is the latter that we are most concerned with for this study. You are probably familiar with some of this messaging already. The short film Duck and Cover (1951-52) is the most famous of these messaging efforts: a short film, aimed at an audience of children and meant to be shown in schools, it gives instruction as to how to recognize a nuclear attack and increase one’s chances for survival from its immediate effects. This includes getting away from windows, making one’s self a smaller target for flying debris, keeping one’s face and body out of direct line-of-sight to the fireball, using shelters if they are available and one has time to get to them, and, of course, hiding under one’s school desk.

One could spend a lot of time dissecting this particular film (and someday, dear reader, we will do just that), but the general point to really take away here is Duck and Cover was:

a work of communication aimed at a segment of the general public (hello, kids!)

largely about individual action (you gotta save yourselves, kids!)

premised on the idea of relatively short-term survival and deference to officials/authorities who will be leading up the post-attack reconstruction effort (the Civil Defense man is your friend, kids!)

ultimately part of an overall plan (however well-conceived, however earnest) for collective survival (you gotta survive so the country can recover, kids!)

There’s a lot more one can say about this film and its goals (and the “goals” of Civil Defense more broadly), but the point that this is about individual action in concert with larger planning for a collective purpose is what I want to get across here as the “essence” of Civil Defense.2

Films were not the entirety of Civil Defense; there were drills, there were endless pamphlets (including those that targeted specific subsets of the “general population,” like farmers and mortuary practitioners), and there were efforts to create group shelters and underground schools and just a whole lot of things. They all follow this broad outline, though, of being part of a collective plan, but still generally relying on individuals to become educated and take initiative toward that end.

The exact recommendations and tactics shifted along with the Cold War. As the imagined attack increased in scope, for example, the possibility of urban centers surviving through the use of “bunkering” techniques dropped considerably, and the emphasis shifted towards tactics of evacuation and suburban fallout shelters.

It is really vitally important to emphasize that Civil Defense is not the same thing as Survivalism or Preppers. Survivalists and Preppers draw upon the research and some (but not all!) of the strategies formulated by Civil Defense programs, but their imagined goals are very different.

The Survivalist/Prepper mindset is about individual survival. It is often (as we will see in Part 2) explicitly anti-statist at its core: it carries with it a deep distrust of, and even antipathy to, government authority. Its adherents tend to be deeply skeptical that the government will protect them, fix things, or even be reconstructed after a major catastrophe. The goal of Civil Defense is always about reconstruction of the status quo, in the same way that Continuity of Government is about maintaining some form of the status quo politically. The goals of Survivialists/Preppers are usually about the survival of their individual selves and their family unit, and about creating some kind of new post-apocalyptic order.

Home fallout shelters

So what is the inflection point between Civil Defense and Preppers? I’ll talk more about that in Part 2, but I want to suggest, for now, what I think the conceptual “bridge” is between the two: the home fallout shelter.

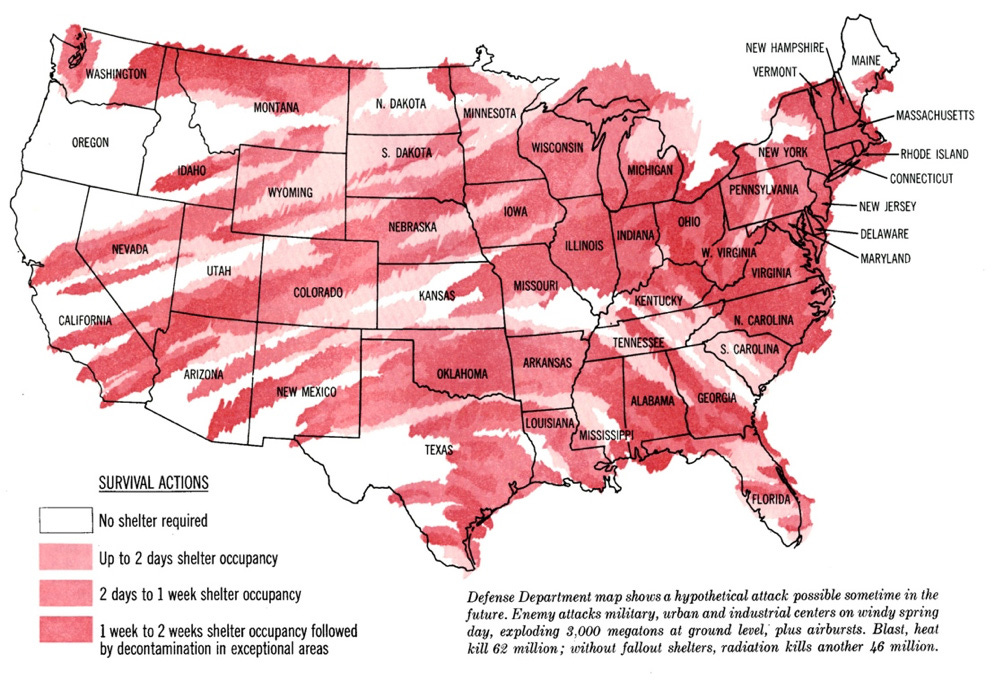

The home fallout shelter program was inaugurated in the 1950s after the development of high-yield thermonuclear weapons made clear that huge areas downwind of military and urban targets would be possibly subjected to high-levels of dangerous radioactive particles descending from the remains of mushroom clouds as they were smeared across the upper atmosphere by the wind. The only possible “response” to such a threat, assuming war happened, was to get the people downwind of the threat into bunkers that would cut their exposure, especially during the early period of the fallout in which the dose rates were lethally high. If they could make it through that period, there would still be a threat of contamination to deal with, but that would be a more chronic threat than the immediate, acute threat.

In 1956, the Federal Civil Defense Administration submitted a $30 billion budget request to the Eisenhower administration for the building of public shelters. Other proposals around the same time put a serious, government-run fallout shelter system in the realm of $20 billion to $150 billion. Eisenhower felt these costs untenable and feared the emergence of a “garrison state.” The idea of spending vast sums of money on shelters was politically unpopular. The plans for a national fallout shelter system were scrapped.3

In its place emerged a much cheaper approach: try to convince people to build their own shelters, at their own cost and with their own labor. So instead of spending (a lot) of money on building infrastructure, you are spending money on making pamphlets and advertising, exhorting people to save their own families by building up cinderblock areas in their basements.

This, of course, presumes that a) people own houses and have basements or other convertible spaces, b) people have the necessary money and time, and c) people believe this is a worthwhile activity. All of which are large presumptions, and the evidence is that very few people actually built home shelters, even after the bigger fallout shelter push made during the Kennedy administration. (The Kennedy administration, along with pushing for personal shelters, also pushed to identify spaces in existing building that could be used as community shelters — the source of the once-ubiquitous fallout shelter signs. That is a different program to talk about a different day.)

The ideal fallout shelter was not meant to be used for very long. The decay rate for nuclear fallout is very steep: within 48 hours, the radioactivity will have reduced 100 fold. The most contaminated areas were imagined to require perhaps 1-2 weeks of sheltering; many would require only a few days to reach “safe-enough-to-leave” levels. Even two weeks in a basement, much less a buried metal tube, sounds fairly hellish to me, but the point is that this is a relatively short amount of time.

Which is to say, these were not "bunkers” in the Prepper sense. They are not meant to be occupied for long periods of time, they are not meant to be self-sufficient. They are not even totally cut off from the outside world. They are temporary shelters that would serve a very specific, short-term purpose: protect against the worst acute radiation, and then allow people to emerge and participate in the great task of rebuilding society.

But I think this push for self-sufficiency is where we can see the embryonic link between the collectivist, statist project of Civil Defense and the the self-sufficient, individualist goals of the Preppers and Survivalists. However you dress it up, the message of the home fallout shelter is you’re on your own. If you have doubts that the government will survive such a war, then the movement from survive for a few weeks to you might need to survive a very long time, indeed is not such a big one.

In conclusion: it is important to see that there is a pretty big distinction between Civil Defense and Preppers. They are conceptually and historically linked, with the home fallout shelter as arguably the “bridge” between the two approaches. But the Civil Defense administrator doesn’t even want Preppers. They want prepared citizens, but citizens who will follow orders — not hyper-individualists, certainly not anti-statists. They want people who will participate in an orderly rebuilding of the pre-existing society, of a restoring of the “old order.”

In part 2 of this series, I will talk about the emergence of the first true “Prepper” types in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the full-fledged development of Survivalism.

For an excellent book on all of these programs, but with a heavy emphasis on Continuity of Government, see Garrett M. Graff, Raven Rock: The Story of the U.S. Government's Secret Plan to Save Itself — While the Rest of Us Die (Simon & Schuster, 2017).

For a more in-depth discussion of the ideology of Civil Defense, and a comparative study between the US’s and the Soviet Union’s Civil Defense programs, see Edward Geist, Armageddon Insurance: Civil Defense in the United States and Soviet Union, 1945–1991 (University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

For a great history of fallout shelters in the United States, both individual and collective, see Kenneth D. Rose, One Nation Underground: The Fallout Shelter in American Culture (New York University Press, 2001).

In the current era, I feel like my understanding of the connotations of "Survivalist" are more positive than "Prepper". A survivalist is often shown as someone like Bear Grills, being more about wilderness survival, shelter building, hunting, finding water, starting fires etc. Maybe the meaning of the term has shifted?

I have also seen a resurgence on queer/left social media mocking the individualist preppers as gun nuts just happy to shoot "looters" as a dogwhistle for minorities, playing up their lack of preparedness to actually be a subsistence farmer. I saw a post today advocating for people to start growing potatoes in backyards to mitigate against tarrif based food price increases.

I feel there is an overlap in zombie based media with the prepper mindset, where having lots of guns and getting to shoot "zombies" is seen as almost desirable. In the 2000's there were a bunch of people who were preparing for zombies because it was fun, and prepared you for anything else also.

I believe your definition of prepper is too narrow. It may suffice for your purposes but to me prepper casts a very wide net and is not limited to those whose world view is apocalyptic.