Lord Byron's "Darkness"

One of the earliest works of post-apocalyptic fiction in English, from the "year without a summer"

There’s no hard line between the genres of the “apocalyptic” and the “post-apocalyptic.” The Old and New Testaments, for example, contain many examples of “apocalyptic” writing, such as the Flood or Revelations, but is not particularly “post-apocalyptic,” in that it does not spend almost any time dwelling on how the survivors of disaster went on in a changed world. To me, the latter is the key factor in identifying something as “post-apocalyptic”: it becomes a story in which the “apocalypse” in question shines a lens on some aspects of humanity itself.

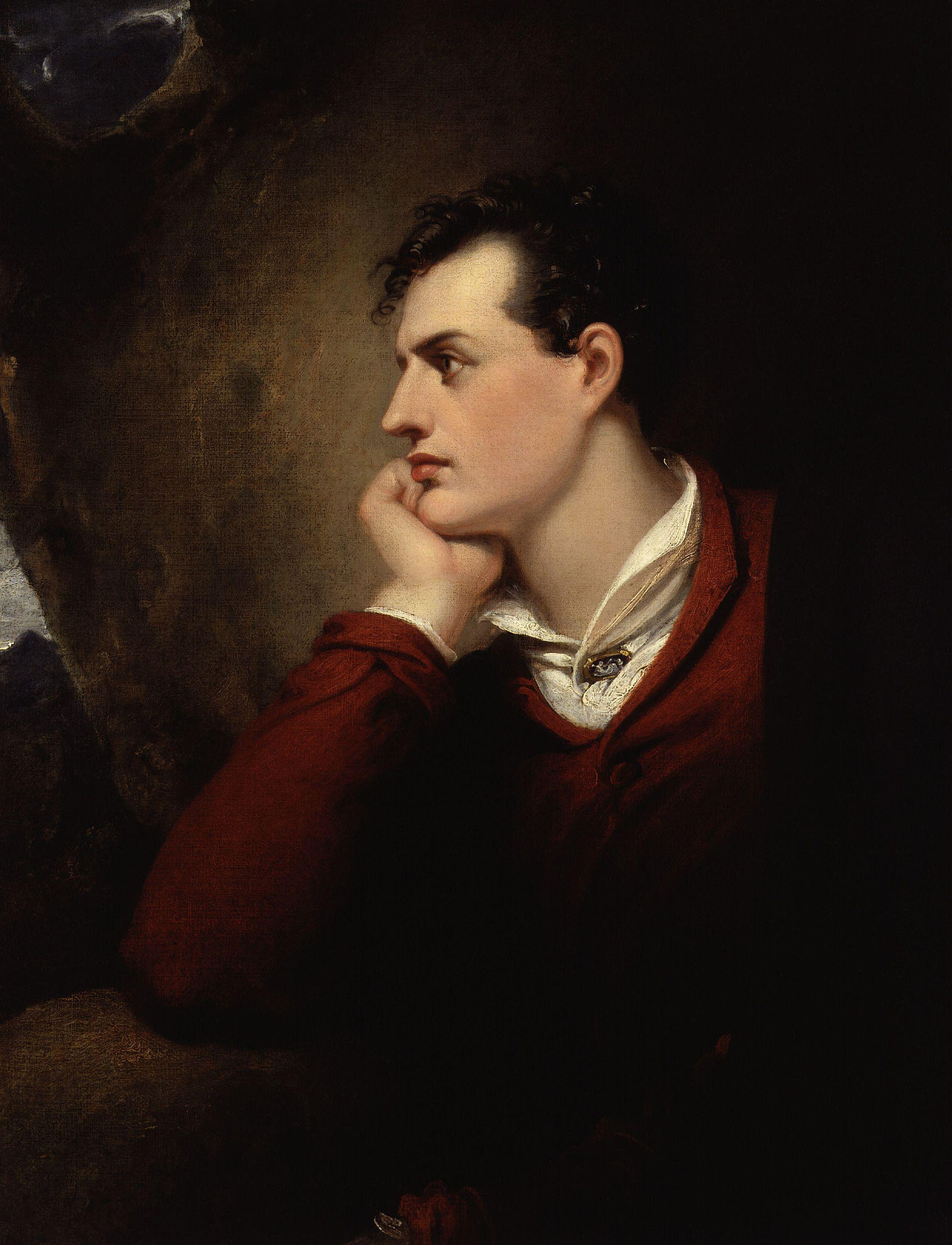

When looking for early examples of true “post-apocalyptic” literature, one work that is often cited is a poem by Lord Byron (George Gordon) from 1816 titled “Darkness.” The poem, which depicts a world in which the “bright sun was extinguish’d,” is frequently cited as having been inspired by the “year without a summer.” As a result of the massive eruption of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia in 1815, particulate matter in the upper atmosphere caused Europe (and elsewhere) to suffer a noticeable temperature drop and dimmed sunlight, a condition that inspired a number of artists to create dark, moody works.

I am not a Byron scholar (or much of a poetry reader at all), but a cursory glance at the biographical/analytical literature on Byron makes it clear that simply attributing this to Tambora and a lack of sunshine is probably incomplete, in the sense that a simple causality between Tambora and “Darkness” is probably missing a few steps. There were other rather “dark” things going on in Byron’s life that year.

Here is how Geoff Payne summarizes the period in his, Dark Imaginings: Ideology and Darkness in the Poetry of Lord Byron:

It is easy to comprehend the appeal of approaching “Darkness” through the framework of his biography. 1816 saw the very public collapse of Byron’s marriage and his behaviour in relation to the separation was minutely scrutinized and severely censured in the press. The year also saw the beginning of his European exile, a decision necessitated by his desire to escape from circulating rumors of incest and sodomy, as well as the severely compromising financial situation that called into question both his character and name. The resultant separation from friends and family (especially Augusta and his infant daughter Ada1) also tried him sorely, while the birth of a second daughter (Allegra, illegitimate with Claire Claremont) presented yet another set of challenges. Given the number of crises Byron faced it is not surprising that the year was memorable and required processing.2

Yikes. Whatever the multitude of causes, it’s a fascinating work. It is impressive to me to see how many standard tropes of the post-apocalyptic genre can be found in it, such as a rapid shift of values (what was once sacred become kindling), a brief period of peace followed by a war amongst survivors for any remaining resources, and, to my greatest surprise, a post-apocalyptic man’s best friend.

This version comes from the Poetry Foundation. I have added a few footnotes to call out aspects that particularly struck me.

“Darkness”

by Lord Byron (George Gordon), 1816

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;3

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chill'd into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires—and the thrones,

The palaces of crowned kings—the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum'd,

And men were gather'd round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other's face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain'd;

Forests were set on fire—but hour by hour

They fell and faded—and the crackling trunks

Extinguish'd with a crash—and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil'd;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and look'd up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past world; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnash'd their teeth and howl'd: the wild birds shriek'd

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl'd

And twin'd themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless—they were slain for food.

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again: a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left;

All earth was but one thought—and that was death

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails—men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devour'd,

Even dogs assail'd their masters, all save one,4

And he was faithful to a corse,5 and kept

The birds and beasts and famish'd men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lur'd their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answer'd not with a caress—he died.

The crowd was famish'd by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies:6 they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heap'd a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they rak'd up,

And shivering scrap'd with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other's aspects—saw, and shriek'd, and died—

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend.7 The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless—

A lump of death—a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirr'd within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp'd

They slept on the abyss without a surge—

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before;

The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish'd; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them—She was the Universe.

Geoff Payne, Dark Imaginings: Ideology and Darkness in the Poetry of Lord Byron (Peter Lang AG, 2008), on 33.

My reading of the “catastrophe” is that it is more Tambora-related (a cloud) rather than being in the “dying Sun” genre.

Could this be the first instance of a post-apocalyptic dog friend? At some point I will write up a survey of post-apocalyptic pets.

Note: Archaic word for “corpse.” (I had to look it up.)

An odd variant on the “last man” approach — two “last men,” and they don’t like each other.

What a great line!

"Darkness" is amazing--managing to combine two of my favorite things, post-apocalyptic fiction and Romantic poetry. It's the only poem that's managed to genuinely frighten me!

The Rest is History podcast recently did a series covering the life of Lord Byron that was highly illuminating