Survival of the Relocated Population of the U.S. after a Nuclear Attack, 1976

The surprising secret to surviving a nuclear war is... to not be near the bombs when they go off

In June 1976, Oak Ridge National Laboratories published a 200-page report on “Survival of the Relocated Population of the U.S. After a Nuclear Attack” as ORNL-5041, authored by Carsten M. Haaland, Conrad V. Chester, and Nobel Prize-winning physicist Eugene P. Wigner.

It would become one of the most-cited reports on the possible consequences of a nuclear attack within the Civil Defense literature — and just as often in the anti-Civil Defense literature. It was, for the time and for a while afterwards, one of the most detailed attempts to consider the consequences of a full-scale nuclear attack by the Soviet Union, particularly during what it terms the “survival period” of a few weeks to a few months after the attack. 1

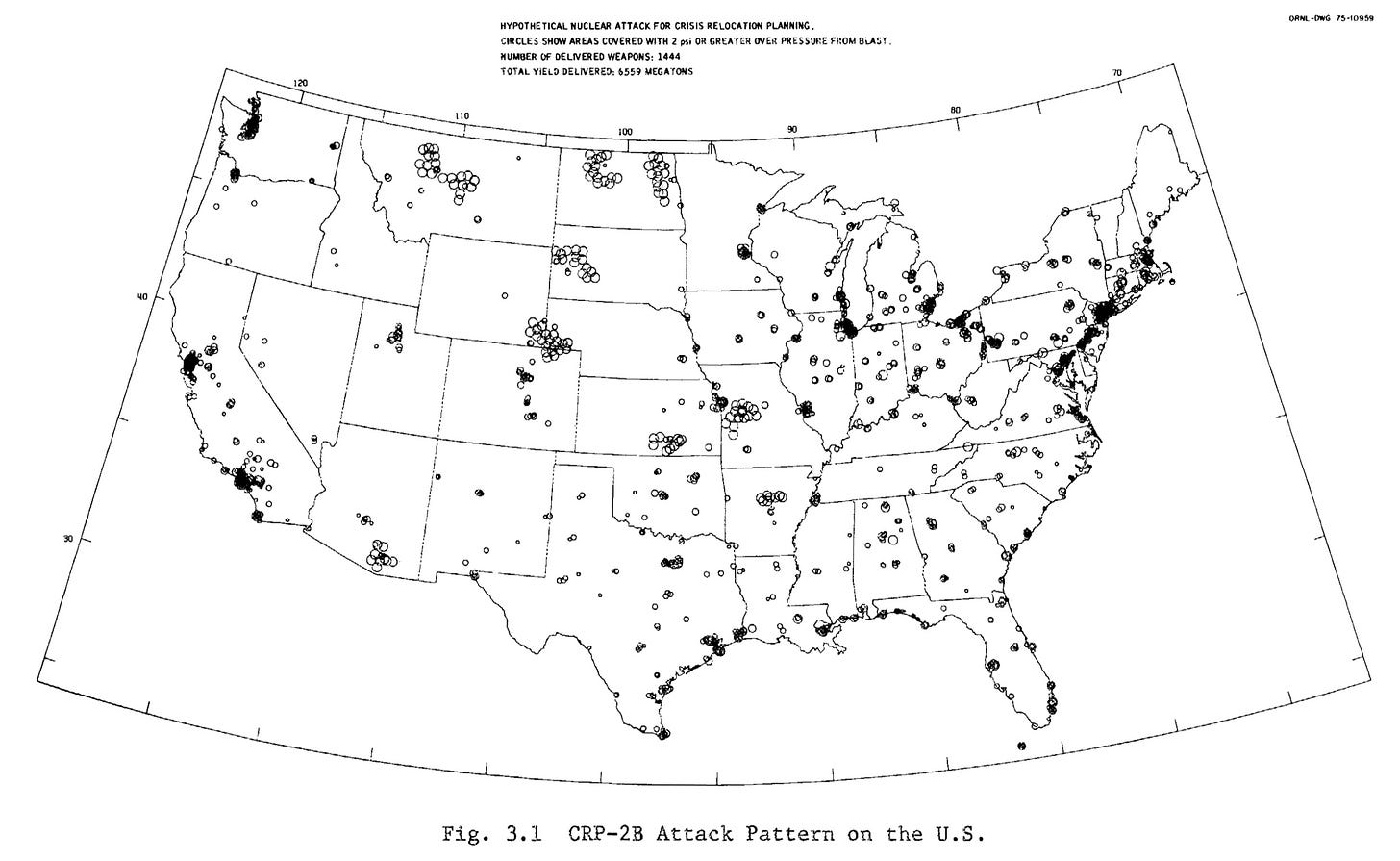

The basic war scenario is one developed by the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DPCA), the Department of Defense-based predecessor of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which had the internal name of CRP-2B.2 This “attack pattern” was developed as a hypothetical list of targets that the Soviet Union might aim at, based on assumption that the Soviets would be targeting, in order of priority:

U.S. military installations

Military-supporting industrial, transportation, and logistics facilities

Other basic industries and facilities which contribute to the maintenance of the U.S. economy

Population concentrations of 50,000 or greater.

A list of targets that met that criteria was then combined with assumptions about Soviet nuclear capabilities in 1980, and from that the “hypothetical attack” was generated, assuming the Soviets had 1,444 “detonated weapons,” with yields ranging between 1 and 20 megatons each, against many hundreds of targets in the contiguous United States:

Now, is the CRP-2B attack plan a realistic one? That’s a separate question, and one I’ll return to in a later post. Certain aspects of the assumptions are not totally in line with what we now know about Soviet arsenals and their targeting philosophies. But the point of the plan wasn’t to be a prediction. It was meant to be a place to start from in terms of making plans for survival, and is probably intentionally pessimistic in certain respects.

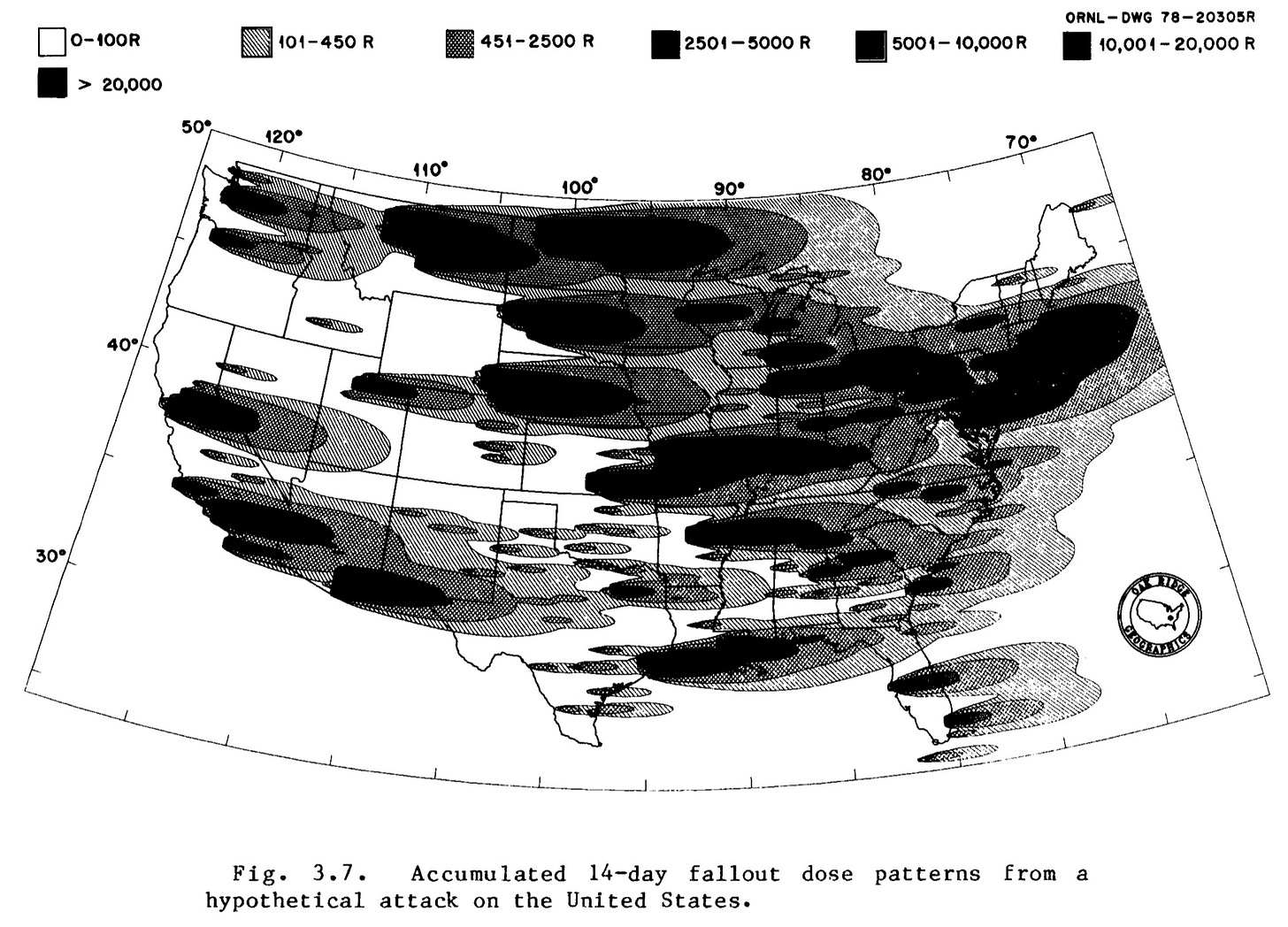

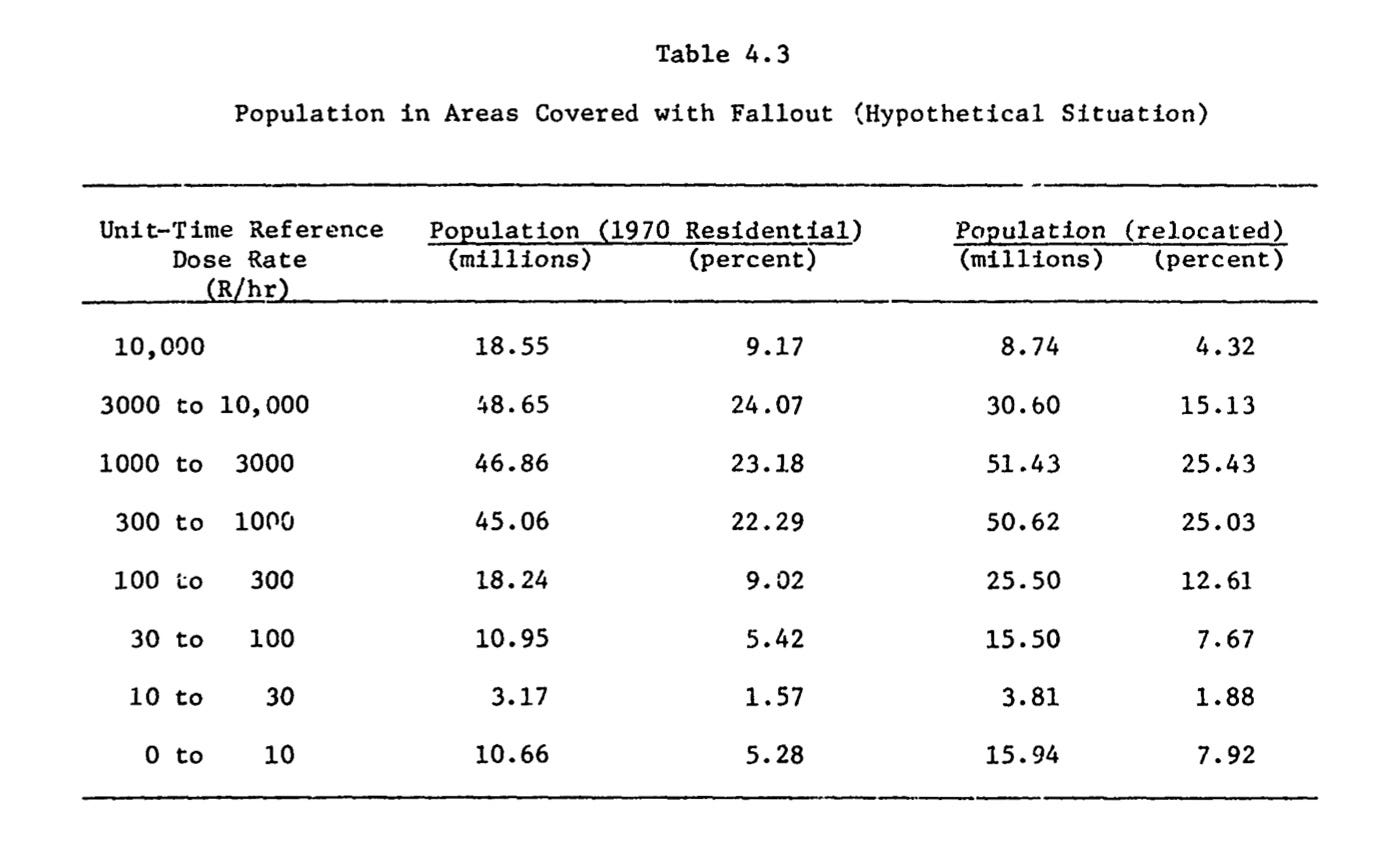

The CRP-2B plan assumed that only 470 (32%) of these detonations would be fallout-producing ground bursts, but that because of the high yields of these weapons (as the map above makes clear, they assumed that the attacks against ICBM silos would all be 20 megaton weapons), they would make up 77% of the total megatonnage: 5,051 out of 6,559 megatons would be fallout-producing.3 The authors used simplifying assumptions (constant wind speed, and all weapons detonating at the same time) to come up with a rather impressive map of fallout distribution:

None of the versions of the above map (or the original it is based on) are of such good quality that one can distinguish between all of the “high” levels of exposure, but they are so high that it feels almost pointless to want to. As a thumbnail rule, 100 R (Roentgens) is enough to make someone sick (and measurably increase their lifetime cancer risk), and 500 R (or thereabouts) is often used as the threshold for when it starts to get significantly deadly. Once you start talking about 1,000 R exposures, much less upwards of 20,000 R exposures, you are almost certainly talking about fatal exposures. So anything that is on that map that is not perfectly white is sickening at least, and all shadings above the lightest are fatal exposures.

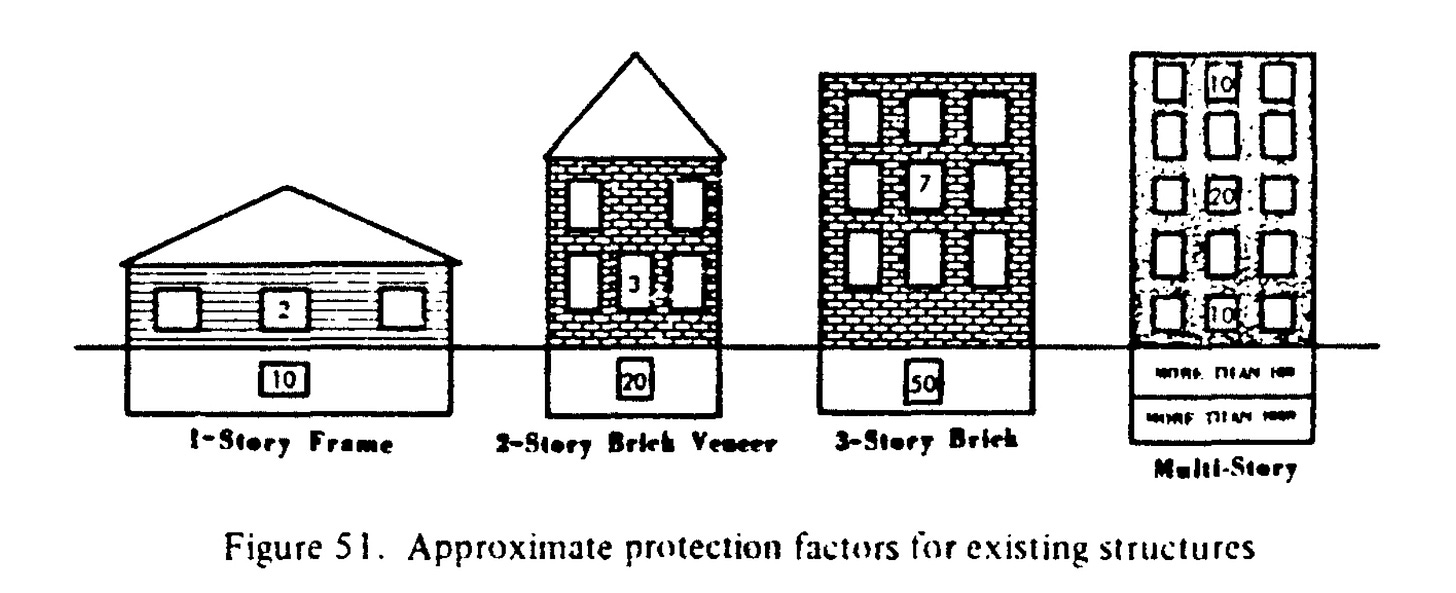

Now, these are the exposure doses for someone sitting outside and doing nothing for two weeks. Any kind of barrier between you and the fallout would reduce these exposures by some amount. A good shelter could reduce it significantly — some purpose-built shelters might have a Protection Factor (PF) of 1,000, meaning that you would receive 1/1000 of the reference dose. Most shelters, they concede, would have a PF of less than 200. The ground story of a single-story house might have a PF of 2, for example (so you would receive 1/2 of the reference dose), while a basement of such a home might have a PF of 10 (so 1/10 of the reference dose). So if one is talking about a 1,000 R exposure over two weeks, then your basement might knock that down to 100 R (sickening, but not fatal), but just staying inside your home would only knock it down to 500 R (likely fatal).

Such is the grim calculus of such studies. This particular study has a lot of interesting aspects, which I will come back to in future posts, but it is no surprise that one of the two “major problems” for post-attack survival the authors identify is securing adequate shelter against fallout (the other one is food availability, which is not unrelated).

But what makes this particular study stand out is that it was commissioned by the DCPA with a very specific “Scope of Work” that defined very narrowly the assumptions that the scientists were required to make when performing the analysis. Specifically, the study was required to assume that (emphasis in original):

At a time in the not too distant future an international nuclear crisis has occurred;

The U.S. Crisis Relocation Plans in accordance with currently conceived elements have been implemented;

That radiological protection has been provided and used, again according to currently conceived ideas; and

That a nuclear attack on the U.S. of a magnitude within that considered consistent with current SALT weapons limitations has occurred.

Point #4 is the CRP-2B attack scenario, but points #1-3 are much more dramatic. They refer to (very hypothetical) plans in place that would involve simply moving everyone in a high-risk area somewhere else. Which is in some ways a very logical approach to surviving a nuclear war: don’t be around when the bombs go off! But as a practicable plan for the entire country, it is… well, it is a lot.

Perhaps I am reading too much into this, but there are times in which the study’s authors appear to be signaling to whomever is reading them that they understand that these are rather large assumptions, such as their introduction to their Conclusion:

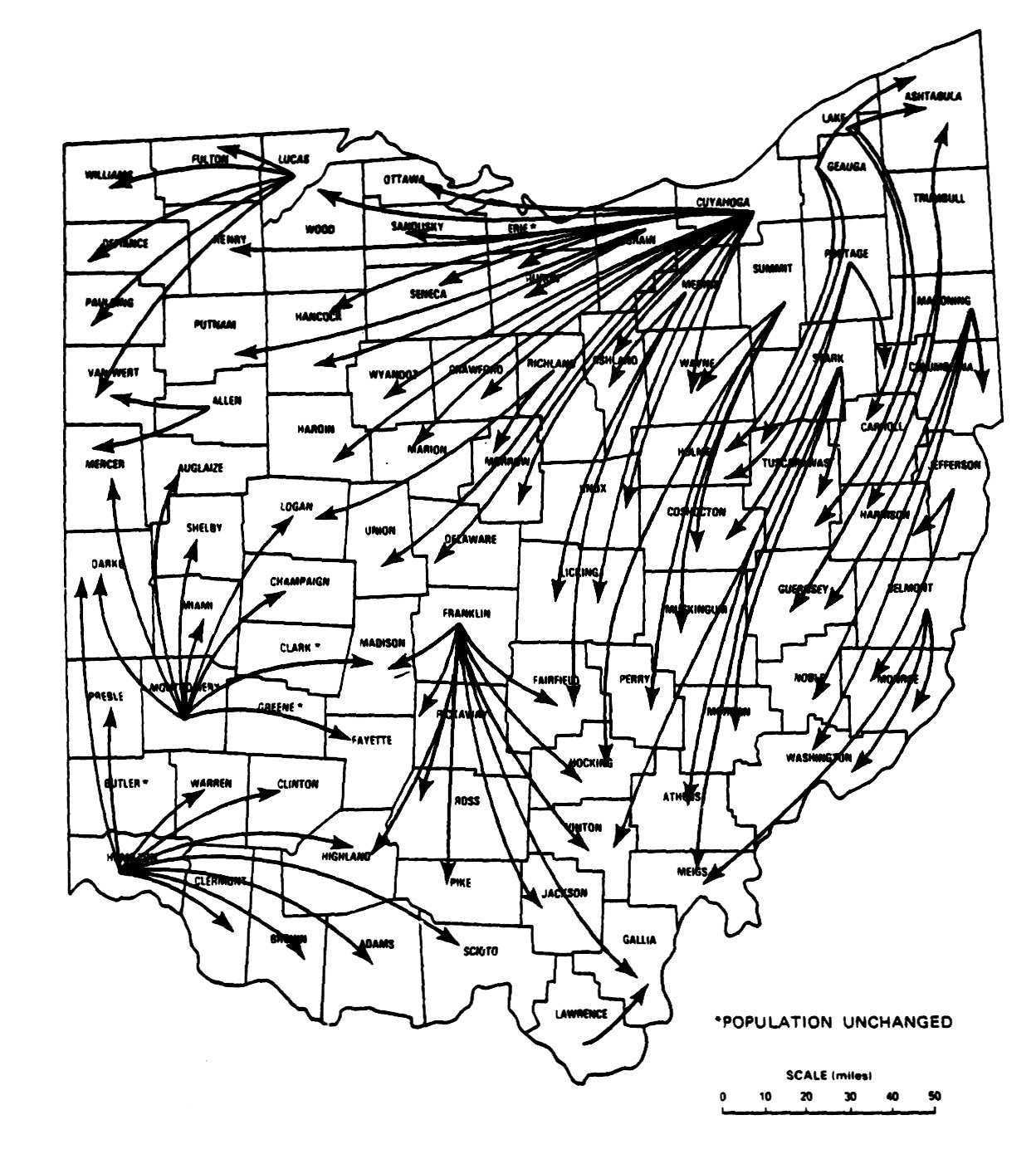

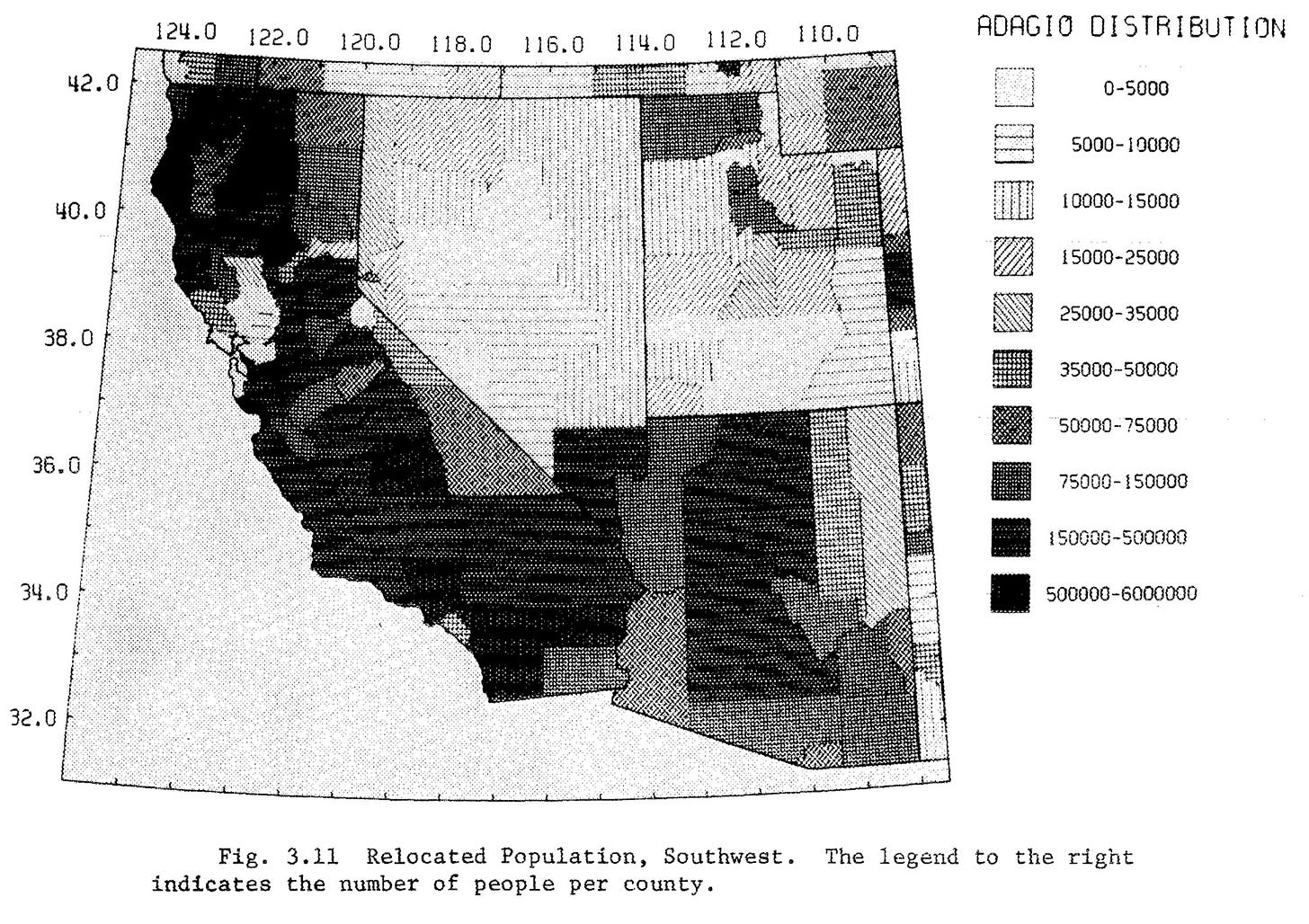

Under the assumptions specified for this research program in the Scope of Work statement, we are to assume that people in high-risk areas are relocated “in accordance with currently conceived elements,” one of which was the ADAGIO computer program which assigns 89.6 million people to host areas. According to this assignment, about 90% of the U.S. population would be located remote from the blast and fire effects of the nuclear weapons of the 6,559 MT attack, and would therefore survive through the attack period.

Also, according to assumptions specified in the Scope of Work statement, we are to assume that “radiological protection has been provided and used during and after the attack,” again according to currently conceived ideas. The fallout radiation from the specific 6,559 MT CRP-2B attack is more severe than most attacks which have been considered in the past, and it may be necessary to increase the protection factor requirements of shelters to cope with the increased threat.

So this entire post-nuclear attack scenario, which is very carefully researched, is based on the premise that 90% of the US population has been relocated to places where nukes will not be aimed at several weeks before the attack occurred, and that they have already been given sufficient fallout protection during and after the attack, and that otherwise things are going pretty well. This is a very optimistic assumption to say the least.

Just think, for a minute, about what that would require. You’d need the US President to decide that things were dangerous-enough in the world that he was going to order 90% of the US population to leave their homes for an indefinite amount of time because of a fear of an imminent nuclear attack from the Soviet Union.

The political costs of such an order are unimaginable. Aside from the panic it would generate, it would essentially shut down the entire economy of the United States. I think this is one of those areas where those of us in the 21st century have perhaps more experience, both with disasters like Hurricane Katrina (which highlighted so many issues and inequities with mass evacuation attempts) and the economic, political, and social impacts of suddenly having a large portion of the economy shut down during COVID (which of course would only have been a fraction of the consequences of the kind of evacuation the study contemplates).

The actual logistics of such an evacuation of tens of millions of people boggle the mind, especially when one considers the large number of Americans who would lack vehicles and could not transport themselves (because of age, medical status, etc.). Imagine then how the locals in these “low risk areas” would feel about suddenly having an influx of tens of thousands of fearful out-of-towners suddenly deposited in their jurisdictions for an indefinite amount of time. The study calculates the “relocating hosting factors” — the ratio of out-of-towners to locals — for a number of states, and the minimum factor is 3.5 (Colorado), and the maximum is 9 (California).4

How would this possibly work, in practice? How would freeways and chokepoints not become horribly clogged with fearful, angry, unhappy people? Would not the movement of 90 million people over the course of 14 days or so be one of the greatest mass migrations, in terms of density of people in time and space, ever accomplished in global history? As a point of reference, the partition of India in 1947 involved the swift movement of some 10-18 million people over the course of a few months. The conditions would not be quite the same — though one could hardly think that the nuclear relocation would much less politically and socially fraught — but up to 1 million lives are thought to have been lost during the partition.

And that’s just the domestic side of the problem. Such a mass relocation of people would not, of course, go unnoticed by the Soviet Union, and would be a sure signal that the US was expecting to engage in a nuclear war swiftly. What effect would such a thing have on US-Soviet tensions, which must have already been high if it such an order was going to go through in the first place? Would such an action not be taken as a sign by the Soviets that nuclear war was inevitable, given the political and economic costs that the US would be incurring in undertaking it? And what of NATO, US allies, the rest of the world? Again, it is hard to see under what conditions the US political and strategic system would actually believe that making such an order would be the appropriate choice, even if it believed nuclear war was very likely in the next few weeks.

There is at least one place in the report where the authors seem, again, to be undermining its assumptions: the “scope” assumptions imagine that practically every American at risk of being near a nuclear explosion has been relocated away from them. But what if that didn’t happen? The authors note that under those conditions, 125 million Americans would be exposed to around 2 psi of blast overpressure (enough to break windows and cause other kinds of “light” damage), and about 58 million would be exposed to 15 psi of blast pressure (enough to cause extreme damage to any civilian structures). Those are huge numbers! The authors point out that even without relocation, there would be a lot to be said for providing blast shelters for people but… that is a lot of blast shelters, for a lot of people at risk.

But such things aside, the authors dutifully try to remain optimistic about Civil Defense. If everyone was evacuated, and if everyone evacuated had adequate shelter, and if central control by government was continued throughout this totally overwhelming attack, and if actions were immediately taken to restore logistics, communications, electricity, food supply, water supply, petroleum production, and so on… then you can imagine a very large percentage of the United States surviving and rebuilding the nation.

Which, at least for me, sounds very improbable. In a way, this kind of report feels like a much worse condemnation of late Cold War Civil Defense plans than the anti-nuclear analyses that were being made at the time (and really flourished in the 1980s). Because the anti-nuclear studies tended to make much more pessimistic assumptions about the attack, about government response, about evacuations, etc., but this one uses what are quite possibly the most unrealistically optimistic assumptions one can make and it still sounds impossible.

This report is part of the 1970s-era of Civil Defense work (like the 1973 DCPA graph I previously profiled) that I find totally fascinating because it falls in a strange cleft of the “official culture” between the shelter-optimism of the 1960s and the Reagan-optimism of the 1980s. It tries to be optimistic, but they’re actually trying to crunch the numbers, and the numbers aren’t quite coming out all that well. They try to find ways to put positive spins on them… but one feels that, at some level, their heart isn’t entirely in it. Or maybe that’s just how it feels to me reading it back now.

The problem, at its heart, is that this kind of mass evacuation plan just doesn’t feel all that plausible. Arguably, evacuation plans of this scale could never be plausible — just try to get into or out of the New York City metro area (or Bay Area, or Los Angeles, or pick-your-urban-area) on a holiday weekend, and then imagine what would happen if it was done under imminent nuclear war conditions. Add the high yields of 1970s-1980s weapons with the fact that the flight times of ICBMs are measured in minutes, and you don’t have a lot of hope for urban areas unless you assume you can evacuate people well in advance. And that, it turns out, is a huge assumption in and of itself, for the reasons I’ve outlined.

But what’s the alternative for a Civil Defense planner? To admit that the cities are toast, essentially, and with them, a significant fraction of the national population. Which turns out to be a very hard thing to face up to, as obvious as it was, I think, to most people at the time. This was, and still is, a persistent failure of Civil Defense planners, I think, but at least in the 1970s, they don’t quite paper over it as thoroughly as they frequently did in other eras of planning.

Carsten M. Haaland, Conrad V. Chester, and Eugene P. Wigner, “Survival of the Relocated Population of the U.S. After a Nuclear Attack,” ORNL-5041 (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, June 1976). There are two main versions of this report online: this low-contrast scan from OSTI.gov, and a high-contrast microfilm scan from the DTIC. If anybody has access to an original and wants to make some better scans of the images, let me know! I would love a better scan of the fallout map (Figure 4.1, on page 38).

The history of CRP-2B is a little unclear to me, despite it being cited and talked about quite a lot in the 1970s and 1980s. There is a lot of obviously incorrect information about it on the Internet and in historical publications, many of which attribute it to FEMA, even though it clearly predates FEMA. The acronym CRP stands Crisis Relocation Planning, the evacuation model that gained official interest starting in 1974, but what the “2B” indicates — presumably that multiple, different scenarios were also contemplated — is not clear. It appears based on a target list from a previous DCPA publication, High Risk Areas for Civil Preparedness Nuclear Defense Planning Purposes, TR-82 (Defense Civil Preparedness Agency, April 1975), but that particular publication doesn’t actually contain a ranking of targets or a description of the kinds of weapons needed against them, so some other kinds of transformations clearly must have taken place with the data.

“Local fallout,” the kind that produces high contamination on the ground in the classic fallout contours and plume, is largely caused by ground or near-surface detonations. Weapons designed to maximize medium- and low-amounts of blast damage (such as those targeting cities) are assumed to be airbursts, which produce much less local fallout. There are weather conditions (such as rainstorms) that can cause airbursts to dump some of their radioactive contaminants as fallout (rainout) as well, so this is not a perfect rule. Airbursts contribute to overall global radioactivity (“global fallout”), but when people think of “fallout” they usually are thinking of “local fallout,” which creates areas downwind that are acutely hazardous in the short-term, and can be chronically contaminated in the medium- and long-term.

A point I will return to at a later time is that this particular report was viewed very dimly by the nascent community of “Survivalists,” which would become what we think of as “Preppers” today, particularly because of this idea of “urban” people somehow mixing with “country” people. The class and racial undertones in such critiques were not exactly undertones. It is one of the interesting places where the contrast between (government planned, centrally-controlled) Civil Defense and (hyper-individualist, often anti-government) Survivalism is very clear, despite their mutual affection for “preparedness.”

✍️ don't be...near bombs...when they detonate...✍️

Today many organizations develop all-hazards continuity of operations plans. How does the thinking behind this report comport with such modern ideas? How many of those contemporary plans include a section on nuclear war??