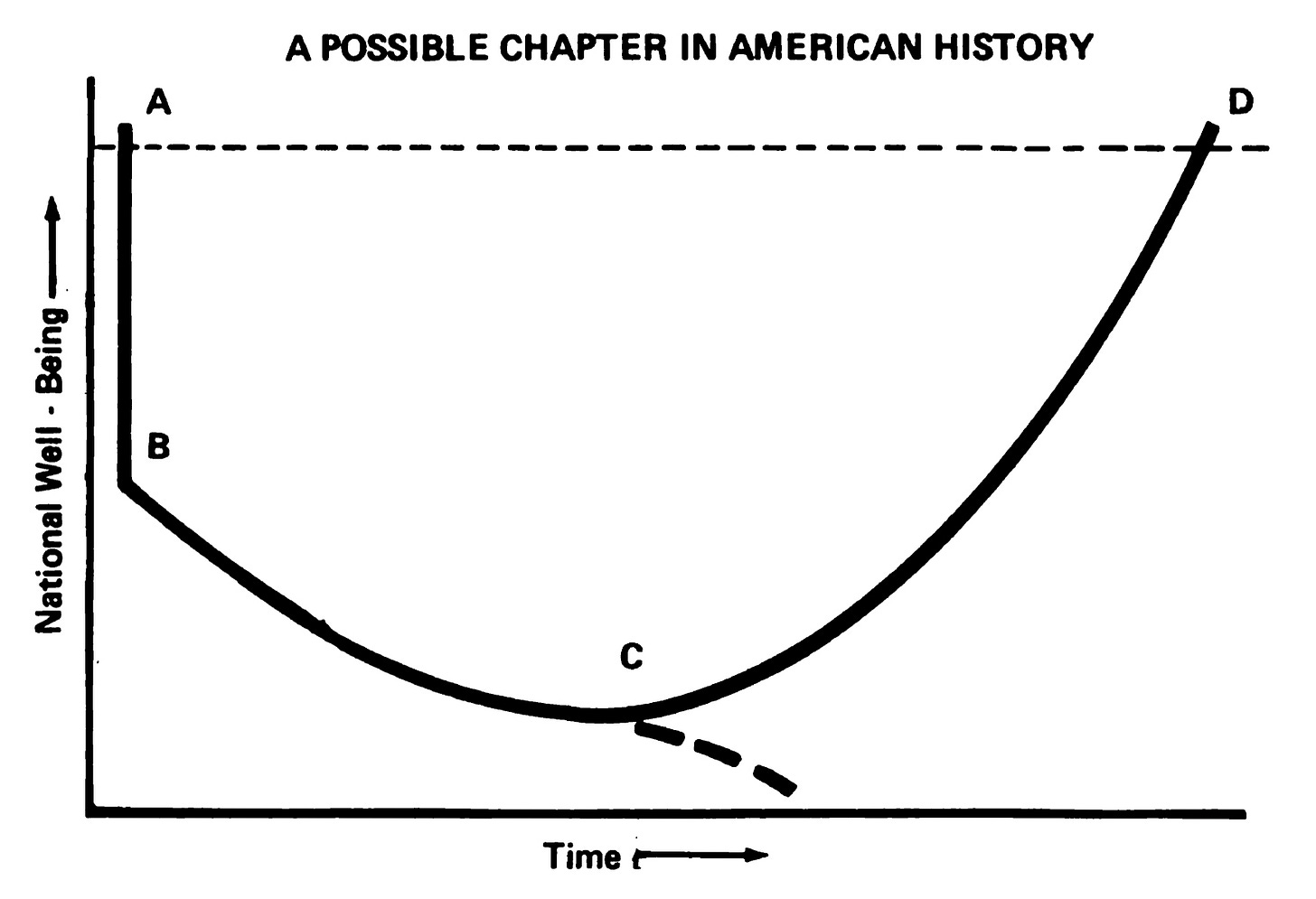

A Possible Chapter in American History

Is this the most honest graph made for public consumption by a government Civil Defense agency?

Between 1972 and 1979, Civil Defense in the United States was coordinated by the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DCPA), which was part of the US Department of Defense. This was a strange period for Civil Defense. The DCPA was predated by several other agencies, like the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA), and was eventually succeeded by Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The DCPA’s output was a lot more inscrutable and a lot less “slick” than the FCDA’s, yet still very focused on nuclear threats, unlike FEMA.

One of their major publications was the Attack Environment Manual in 1973. It’s a bizarre document, and one I’ll be coming back to again. It is designed to help “the emergency planner understand what the next war may be like,” but it appears to have been pretty widely available in libraries. Its tone veers wildly. It has strange little cartoons at the end of each chapter, and even a Seventeen-style self-assessment quiz for determining whether you’re cut out to be a shelter leader. But it’s also a lot more honest than most public-facing Civil Defense output about how terrible a nuclear war would be, using that to emphasize the importance of Civil Defense planning.

The DCPA Attack Environment Manual has what is probably my favorite line graph of all time, labeled “A POSSIBLE CHAPTER IN AMERICAN HISTORY”:1

Here is the relevant text on the page that precedes the graph and describes how it is meant to be understood:

POSTATTACK RECOVERY

Another useful viewpoint for coping with the post-shelter environment is shown here. It is the view that might occupy the attention of the Nation's leaders or that might be described in in a history of the aftermath of a nuclear war.2

National well-being may be be considered as a composite of population, material resources, of material and social and economic institutions—the basic elements that make for a viable country. Prior to the attack, the national well-being is high, as shown at Point A. The immediate consequence of the attack is a sharp drop in well-being (Point B), with millions of dead and injured, great destruction of resources, and disorganization of institutions, such as government, banking, private ownership, and the like.3

It is reasonable to expect that the initial sharp drop would be followed by a further decline in well-being because of continuing fallout radiation exposure, deterioration of abandoned factory machinery, wastage of scarce resources, inadequate mutual aid, lack of communications, and general disruption of normal patterns of living. Initial coping efforts would attempt to “stabilize” the situation and satisfy the most pressing wants so that sooner or a later a minimum or “bottoming out” should occur (Point C), after which the Nation would begin its upward path to recovery (Point D).

There is a possible alternative history that the national leadership will strive to avoid. It is indicated by the downward dashed line at Point C, which implies that deterioration is so severe or management so inept or misdirected that national recovery does not occur at all, and the country degenerates into chaos and anarchy.

This viewpoint focuses on the need for national goals, goals widely shared at all levels of government and among the public at large. No local government nor wider region can recover by itself.4

There’s a lot that could be noted in the above (some of which I could not help but add as footnotes), but the main things that draws me back to this graph, again and again, are:

The drop from point A (pre-nuke “national well-being”) to point B (immediate aftermath) is realistically dramatic and immediate. This is such an obvious truism, yet is almost always totally lacking in any kind of public-facing discourse about nuclear war in Civil Defense literature. Sometimes one finds almost entirely unhinged optimism, an almost overt denial that even a few nuclear detonations (much less hundreds or thousands) would not have a dramatic impact on “national well-being.” At a minimum, it is usually just lacking in any acknowledgment of what everybody knows would be the case.

The gradual “bottoming out” from points B to C also feels like a realistic acknowledgment that “the day after” is not even the worst of it, that the death, injury, damage, disruption, contamination, etc., would continue to compound the misery considerably. That things would get worse before they would possibly get better. The scale of this graph is totally unspecified, but note that the difference between points B and C is about the difference between points A and B, just stretched out further in time.

Lastly, of course, I love what is happening with the dashed line coming off of point C, the acknowledgment that it is entirely possible to imagine that the situation would not improve, would spiral off into “chaos and anarchy.” The text uses this acknowledgment — which of course maps on to what most normal people thinking about this scenario would imagine the consequences of such an attack would be — as a way to frame what the entire goal of Civil Defense is: organizing and preparing so that instead of spiraling off into oblivion, you begin some kind of long, no-doubt difficult rebuilding process that, after some unspecified amount of time, returns the nation to its pre-war status of well-being.

In sum, what makes this graph unusual, for an official publication (albeit a very strange one), is that it actually gives at least some explicit voice to the idea that nuclear war would be extraordinarily painful and possibly not something that could be recovered from, even if it is done in the service of a message about the possibility of recovery.

The failure to acknowledge this very obvious and very commonly-held opinion, as most Civil Defense literature aimed at the general public does, contributes, I think, to the sense of unreality that people often have when it comes to Civil Defense messaging — and as such ultimately undermines the message. Even acknowledging this obliquely goes a long way towards establishing the the message being delivered is somewhat realistic, and the audience more receptive to the deeper, underlying message about the point of Civil Defense: trying (however well) to keep a bad state of affairs from becoming a permanent one. Whether that’s plausible, of course, is a separate question.

This graph is meant to be something to think with and not a realistic representation in any way, but it would be an interesting exercise to ask people what they believed the shape of the curve would be in “real life” under a presumed nuclear war scenario, and perhaps to imagine what scale the different axes might have.

I have cropped this page so that there is less whitespace between the graph and the page header than exists on the actual page, for the sake of legibility.

I find the whole framing of this as a “future chapter in history,” being written after a future nuclear war, to be a fascinating framing device. It’s not unique to this document, of course, but it's playing around with interesting ideas about what the future could be like, and is itself inherently optimistic (it is not, for example, written in Riddleyspeak).

This is a fascinating list of “institutions.” I think if you asked most people to list what “institutions” would be most impacted by nuclear war, “private ownership” and “banking” would probably be a lot lower on the list, with other things taking their place.

I have cut a few lines at the end which, out of context from the previous pages, come off as strange and non-sequitur, but are continuing a series of categories (“nine barriers to well-being”) that had already been established.

The continuing decline is my takeaway from Threads. At first I cried for the people vaporised immediately. Later I decided that they were the lucky ones.

Alex, this is absolutely fascinating -- both for itself, and for what you say of all the other Civil Defense documents. You describe the graph as "a tool to think with", which leads me to wonder about what kind of thoughts all the other non-honest CD documents led to.

Also, a few typos here and there are slipping through and impeding your meaning (particularly in the first quoted paragraph). Some content creators allow early access to some subscribers for review and corrections. Just a thought!