Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) has become the gold standard by which all post-apocalyptic road trips are currently measured. I had always planned for my first post on Doomsday Machines to be about The Road — you have to start somewhere — but I was very interested in the fact that when I told people about my plan for Doomsday Machines, people would immediately ask, “like, The Road?”

The book’s reputation for bleakness, grayness, and grimness is well-earned, as anyone who has read it can tell you. There’s also a movie, which I won’t be talking about right now (because I’ve been avoiding it!).1

If you haven’t read The Road, it tells the story of a father (“the man”) and son (“the boy”) in an utterly dying world: an unexplained apocalypse has just killed pretty much everything off, and the few survivors that remain are almost entirely categorized as either the eaters or the eaten. The world is coated with a layer of toxic ash that has killed off nearly everything, plant and animal alike, and reducing humanity to dwindling, uncivilized numbers. The man and boy travel through this world along the titular road. Along the way, they have mostly bad times, although occasionally they stumble across something… less bad? Very early on, they stumble across what may be the last remaining can of Coca-Cola, an artifact of an earlier time. The man shares this treat with the boy, and we feel the bittersweetness of it, this fleeting joy and its implication of finality.

There’s... more, and it’s mostly bad. Many of the things the travelers encounter — especially those involving other people — are firmly in the realm of horror. Disturbing images of the sort that McCarthy is famous for, the kind of graphic violence that has led a lot of well-read people I know to basically roll their eyes when he comes up in a conversation. Bad men. Bad times. A bit of cannibalism.2

So even the good bits aren’t all that good against a context like this one. For years, my wife and I have discussed the question: is there any room for hope in The Road? Because the world that McCarthy envisions doesn’t exactly hold out a lot of options. It doesn’t feel like the low-point in something that will climb back up again, it feels like, er, the end of the road. The ending of The Road (which I won’t spoil) is deliberately ambiguous, but my feeling is that it is pretty hard to read it as offering up a positive future. The verdict’s in, McCarthy seems to be saying, and humanity’s future is, well, dust.

So what does it say about the early 2000s that the The Road was awarded both the Pulitzer Prize and chosen for Oprah’s Book Club? Some of this might be the sort of accolades that get thrust upon older authors of a certain “stature” whose work was deemed controversial when they were younger. And it’s a genuinely gripping book.

But it’s also an artifact of its time and place. The early 2000s were bursting with grim, post-apocalyptic media — 28 Days Later (2002), The Walking Dead (2003), and World War Z (2006) come immediately to mind as emblematic examples of the rising “zombie apocalypse” trend (I’ll write more on that another time). These are all dark, gritty apocalypses. And The Road feels like the grittiest of the gritty, with its literal layer of toxic ash, and McCarthy’s lack of a desire to give you anything like a real sense of resolution.

I think it’s pretty easy to make rather broad arguments about the zeitgeist of the early 2000s. The effect of 9/11 on the minds of Americans was profound, and one of those things I’ve struggled to convey to my students. It’s not that things were great before 9/11. But it felt like an inflection point, a descent to somewhere terrible, one that various powers-that-be were almost giddy with enthusiasm about pursuing to its deepest, darkest ends.

I don’t think that’s the whole story about post-apocalypticism in the early 2000s (this is a theme that will be returned to in future posts), but I think it’s part of the context for why this book, and these kinds of themes, seem to resonate at the time.

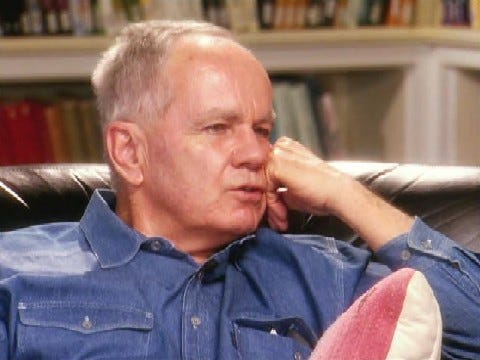

McCarthy was interviewed by Oprah in mid-2007 after she chose the book for her book club (which boosted its sales into the area of 1.3 million, apparently). It’s an odd interview. McCarthy did not really give interviews, and was not exactly a great interviewee. And Oprah was not exactly the best interviewer, in this case. But she did ask him, several times, about where he felt the book came from, for him, and why people responded to it. Here are the parts I found most interesting:3

O: Where did this apocalyptic dream come from?

M: Well, it’s interesting because usually you don’t know where a book comes from. It’s just there, some kind of itch that you can’t quite scratch. My son John, about four years ago, he and I went to El Paso —

O: He’s 8 now.

M: Yeah. And we checked into the old hotel there. And one night, John was asleep. It was probably about 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning. And I went over there and I stood I looked out the window at this town. There was nothing moving, but I could hear the trains going through, a very lonesome sound. I just had this image of what this town might look like in 50 or 100 years. I just had this image of these fires up on the hill, and everything being laid waste, and I thought a lot about my little boy. So I wrote those pages and that was the end of it. And then about four years later I was in Ireland, and I woke up one morning and I realized that it wasn’t two pages of another book, it was a book, and it was about that man and that little boy.

O: Is this a love story to your son?

M: Hmm.. In a way I suppose it is, although it’s kind of embarrassing. I suppose it is, yeah.

O: I just saw you blush! When I called you at first, I said, people want to know, where did this book come from? You said, well, it’s obvious it came because my son practically co-wrote this book.

M: Yeah.

O: Had you not has this son at this time, this book wouldn’t have been written?

M. No. Absolutely not. Never would have occurred to me to try to write a book about a father and a son.

And then a bit later:

O: Are we to ever know what actually happened [in the book]? All kinds of critics and all kinds of fans read all kinds of things into it. Some people say it’s about the journey of man on Earth, it’s about a man’s spiritual journey here on Earth… is that true, or is it just about the man and the boy on the road?

M: Well, I like to think it’s just about the boy and the man on the road, but obviously you can draw, you know, conclusions about all sorts of things from reading the book, depending on your taste. It’s a pretty simple and straightforward story, I think.

O: You know, it’s so interesting, I think if we had read this book 25 years ago, 20 years ago, it would have seemed futuristic. But something about it feels ominous and real.

M: Yeah, I think it is, maybe since 9/11, people are more concerned about apocalyptic issues. We’re not used that.

O: Not accustomed to living in fear, being anxious about what’s going to happen.

M: We’ve had it pretty good. This country’s been lucky. Just like me.

O: So, you know that it’s now on people’s minds, when you were writing it. Obviously it’s on your mind.

M: Yeah.

O: What do you want us to get from this book in particular?

M: Just simply to care about things and people and be more appreciative. Life is pretty damned good. Even when it looks bad. And we should appreciate it more. We should be grateful. I don’t know who to be grateful to, but you should be thankful for what you have.

The idea that The Road is about a) the love of a father for their son, and b) that its message is about gratitude for the present world is, well, a little jarring to me. Both make sense once you hear them articulated. But they’re absolutely not how I read The Road, nor what I think of as the point of post-apocalyptic stories in general.

On love, sure. I can see it. The Road is a story of a father trying to protect and nourish their son in a world gone wrong. It’s ever-present in the father’s fears and concerns, but also his self-sacrificing ways that he tries to increase the odds of his son’s survival and, to the extent possible, enjoyment.

Love is giving your boy possibly the last Coca-Cola on the planet. Love is keeping one bullet in the chamber so you can shoot your boy in the head before the cannibal bands grab him. This isn’t a standard definition of love. But could it be the expression of love under such circumstances? Sure.

But… gratitude? Most post-apocalyptic stories are commentaries on the present in some way, either as a warning (“don’t go down this road!”) or as a dark lens being applied to a society (“we seem civilized today, but watch what happens when chips turn!”). They aren’t usually something along the lines of, “aren’t you glad you don’t live in this horrible world I invented?” That’s an odd take, and an odd goal.

McCarthy makes clear elsewhere in the interview (as he has elsewhere) that he didn’t know where the book was going until he wrote it. His writing style is notoriously stream-of-consciousness.4 As an approach to storytelling, that has its ups and downs.

I think one of the consequences, though, is that it almost necessarily means that such a book is not going to channel a specific “message,” but rather channel a specific mental state.5 And in this case, the mental state of an older author who was thinking about the love he had for his young son, and who was reflecting on his own gratitude at the position of relative comfort he’s ended up in towards the end of his life.

The result is this semantically ambiguous product, a work of art that can be interpreted by different people in different times in different ways. The Road is in some ways one of the more experiential post-apocalyptic novels I’ve read, gesturing impressionistically at its world but not getting too caught up in the act of world-building. And in this case it is almost essential that the book doesn’t explain how the world got the way it was, or where it might be going.

There was a lot of speculation when it came out, and speculation since then, on what the cause of The Road’s apocalypse was. In my mind, it’s largely not that interesting. A lot of people have always assumed it was nuclear, though it doesn’t really match up well with that. I’ve heard people suggest it was perhaps meant to be supernatural in nature, a promised cleansing by fire. McCarthy apparently suggested it might have been a meteor strike. Scientists have suggested the eruption of a super-volcano might fit the bill. What matters, for the purpose of the story, is that it was totalizing and it was relatively quick.

More so than a lot of more deliberate post-apocalyptic futures, The Road’s ambiguity is both its core strength and its chief weakness. It’s what makes it an impressive work of literature. But it also makes it a book that is pretty unpleasant to read twice.

I think it is interesting that much of the post-apocalyptic media that is popular today, by contrast, tends to have more optimistic overtones, more explicit hope, than that of 20 years ago. Perhaps because that dread and sense of vulnerability that was so novel in the early 2000s has become just a bit too… persistent.

I’ve read The Road several times, but the idea of a film adaptation of it has never appealed to me, and the buzz about the film is that it is not a great adaptation — no Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men, anyway. I’ll eventually watch it. But it’s not at the top of my list.

Of McCarthy’s books, along with The Road, I’ve read Blood Meridian (1985), No Country for Old Men (2005), and The Passenger (2022). I’m not sure how I’d characterize the latter; it’s pretty odd (and I haven’t yet read its sequel, so I am probably missing something). I would take issue with the idea that McCarthy’s violence is gratuitous (I think it is always serving a point) or the notion that he is glorifying violence (it never feels like a positive thing, or used towards positive ends), but I would completely understand the idea of not wanting to be steeped in it.

This interview is pretty hard to find online in its entirety. This site currently has an 8 minute excerpt from it, which is where I typed this up.

From much earlier interviews: “My hands do the thinking,” he said. “It is not a conscious process.” … “I can’t explain how one creates a novel,” he said. “It’s like jazz. They create as they play, and maybe only those who can do it can understand it.”

It’s really, really easy to make jokes/comparisons with Kerouac’s On the Road, here, but the more I think over this aspect of it, the more apt a comparison it might be?

Good to see this new project starting up!

Reading Cormac McCarthy is like finding a glow-in-the-dark dinosaur in a coal mine. If you walk through a beautiful park in broad daylight, you likely would never notice it. But if you’re wandering through a pitch dark coal mine with no hope of ever seeing daylight again, that glow-in-the-dark dinosaur is like a galaxy.