The Occasion Instant, 1961

What can be learned from how people responded to false alarms about nuclear war in the late 1950s?

Imagine one day you’re going about your business when suddenly you are delivered a message which says, in essence, that a nuclear weapon is going to be detonating somewhere in your vicinity and you should take shelter. What would you do?

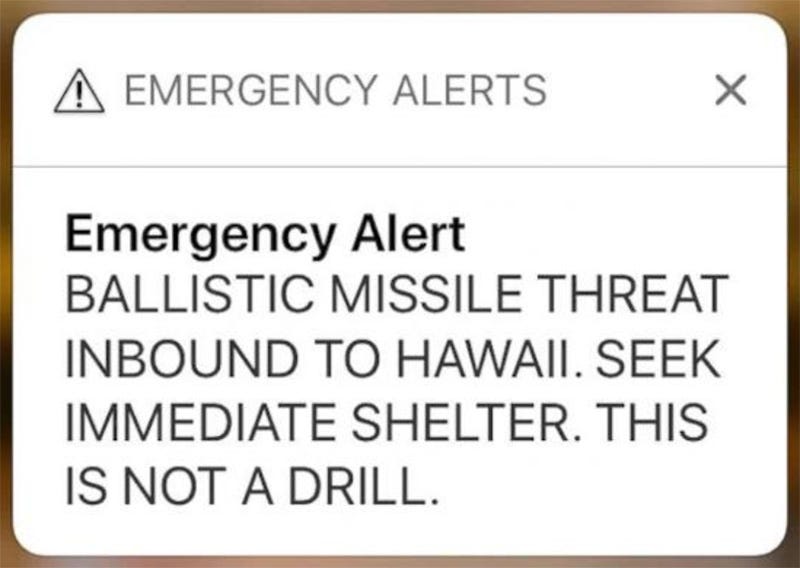

There are a not-insignificant number of Americans who don’t have to speculate to answer this question, because they received just such a message in January 2018, as part of the Hawaii missile alert false alarm. Not much research has been done on what people felt and did on that day, which I think is a huge missed opportunity.1

There’s only one article that I’ve seen that tried to capture that information after the fact, and it doesn’t quite answer the question of “what did people do?” with great specificity. As its abstract concludes: “Participants sought additional information and cues about the potential threat, observed others engaging in milling, and some accounts of fatalism (during the event) and lingering symptoms associated with traumatic stress (after the event).”2

That’s not nothing, and the article has a few more interesting conclusions and responses, but it leaves me with so many questions. When people “sought additional information,” what kinds of sources did they turn to? How did those sources reinforce their views or behavior? How did people react who were alone, versus those in groups of people they knew, versus those in groups of strangers? How did locals react versus tourists? How much did a person’s gender, race/ethnicity, level of education, occupation, etc., change how they reacted? Did having children, or pets, change how people reacted? How many people actually tried to “seek immediate shelter,” as the warning advised them to? What did that look like? What was the role of businesses, especially hotels (again, Hawaii!), in organizing any kind of activity? How many people were these messages even sent to?

These are the kinds of questions I think we’d be asking if we wanted to draw conclusions about what would possibly have happened if it hadn’t been a false alarm. And this is not the kind of thing you can reliably study in an experimental environment: you can’t tell thousands people that they might be dying soon and see what they do as a response (for good reason). And people who know at some level that the threat is definitely not real do not respond the same way as people who have been told it is real.

So this kind of accident/”natural experiment” provides some of the “realest” data we might have… if someone bothered to collect it. But as more time passes since the event, it becomes harder and harder to “recapture” those events after the fact.

If the research agenda I’ve laid out looks really focused and specific, it’s because I have cribbed it primarily from a study that was published in 1961 under the unwieldy title of “The Occasion Instant: The Structure of Social Responses to Unanticipated Air Raid Warnings.”3 Published as part of the “Disaster Study” series of the “Disaster Research Group” of the National Research Council, “The Occasion Instant” is, in brief, a study of what people did in the late 1950s during three nuclear false alarms. The unintuitive title comes from a quote from Hippocrates: “Life is short and the art long; the occasion instant, decision difficult, experiment perilous.” As the Foreword more evocatively explains:

The Occasion Instant of the title of this publication refers to a crucial moment of urgent decision which requires action here and now, if only to decide not to act. The decision must be made quickly, and its consequences may be enormous. To meet the Instant we have to interpret signs of safety and signs of danger. Fortunate is the occasion in which we really know what we are doing.

The study’s three false alarms had quite different circumstances, and took place in different cities and under different conditions:

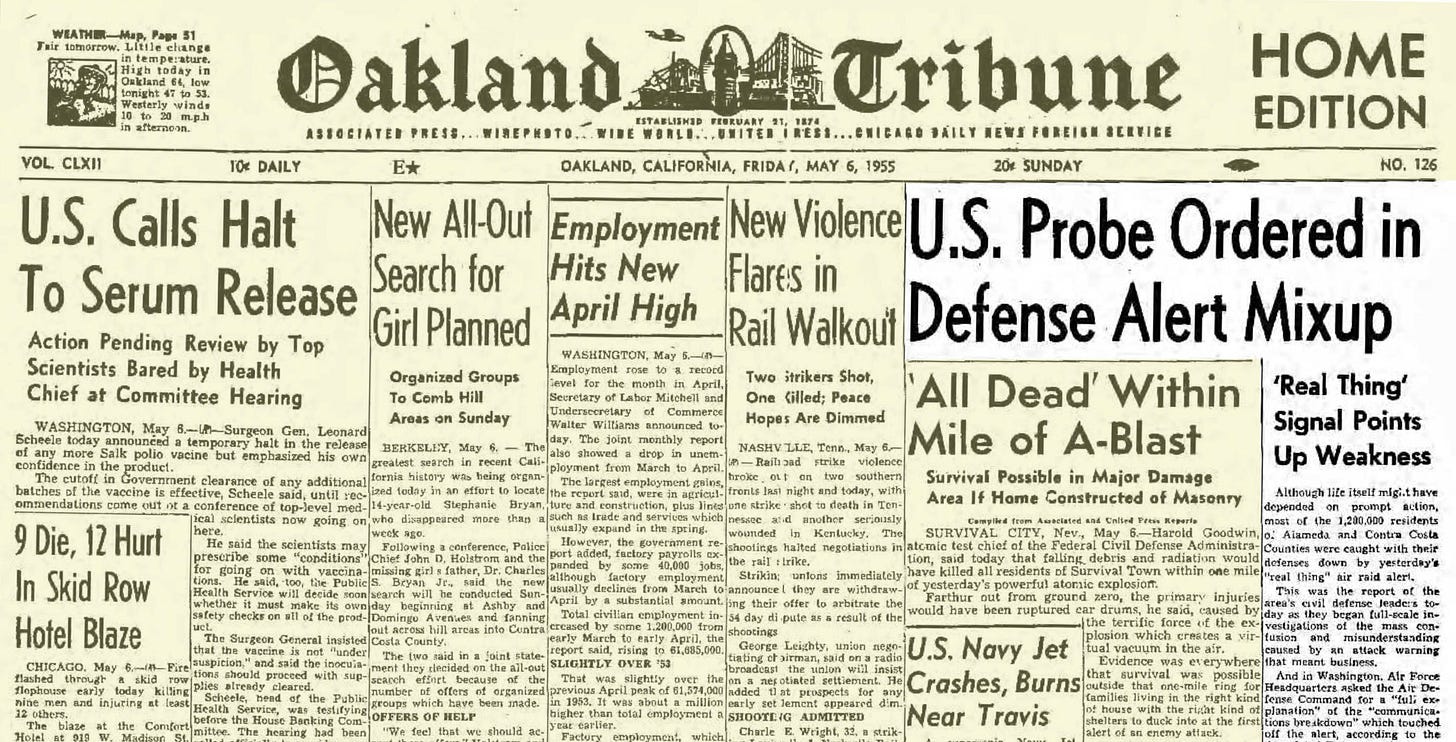

WARNING YELLOW, Oakland, California: “On the morning of 5 May 1955, the United States Air Force was unable to identify a squadron of bombers flying over the Pacific Ocean. The bombers were headed in the general -direction of the central west coast of the United States. An order was given to sound the alert warning sirens for a probable attack. … Sirens sounded Berkeley and in Oakland, California. Radio stations went off the air in San Francisco. Local warnings in schools and business offices (which had internal warning systems) were sounded almost immediately… It took the Air Force only a few minutes to identify the bomb squadron as an American one. All was back to normal in approximately ten minutes. In the same length of time, if the squadron had been enemy-manned and undeterred, it could have delivered a lethal blow.”

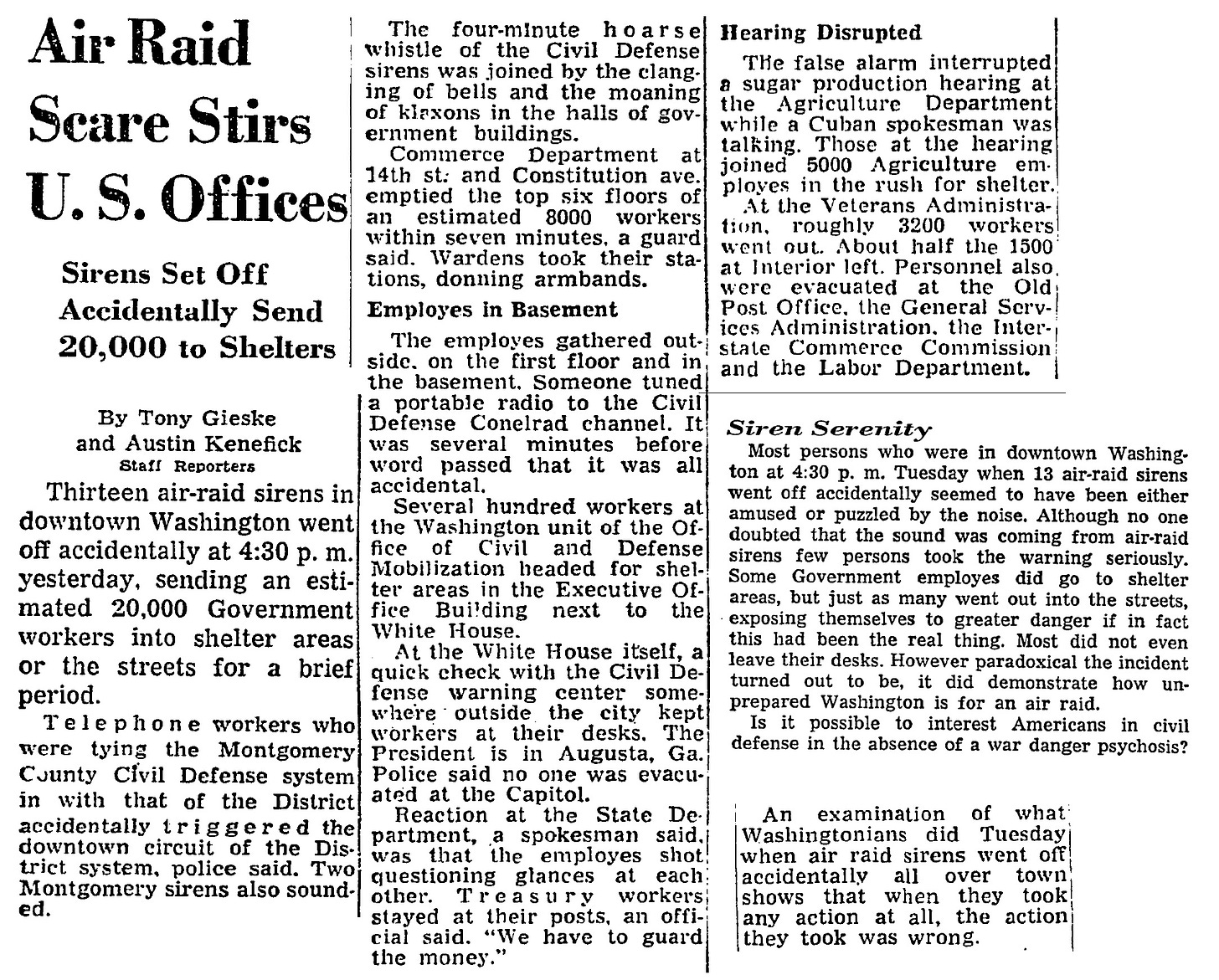

WRONG NUMBER, Washington, DC: “At four-thirty in the afternoon of 25 November 1958, telephone workers in Washington, D.C. accidentally tied in the downtown Washington circuit with the Montgomery County Civil Defense System. Air raid warnings sounded immediately in several parts of Washington, in the downtown area, and inside several establishments which had internal air raid systems connected with the central warning siren. Several thousand Federal government employees, among many others, were thus suddenly exposed to an unannounced and unexpected warning siren, a signal which means literally to prepare for an imminent air attack. The warning signal that sounded was the same one that had been used up to that time only for previously announced practice alerts. However, it should be kept in mind that this was an accidental sounding of the system. Consequently, there were no informed civil defense leaders on hand who knew for sure that this was not a real attack.”

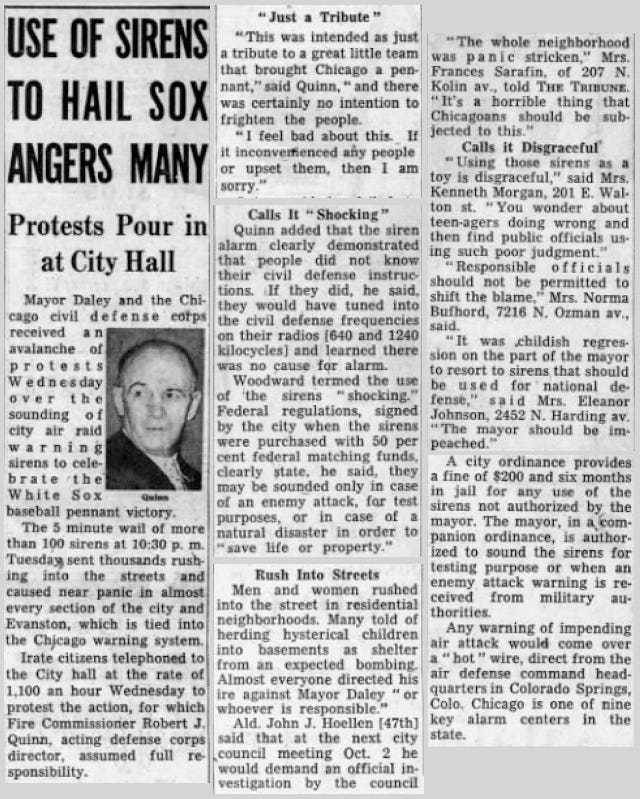

JOY IN MUDVILLE: Chicago, Illinois: “After forty futile attempts in forty successive years, the Chicago White Sox finally won an American League baseball title in 1959. The pennant was clinched when the White Sox won a night game from the Cleveland Indians on September 22, 1959. The game was broadcast and telecast from Cleveland. Just a few days earlier, the Chicago City Council had ‘... resolved that bells ring, whistles blow, bands play and general joy be unconfined when the coveted pennant has been won by the heroes of 35th Street.’ The evening of the ball game, the fire commissioner (also acting director of the city's civil defense corps) decided to sound the civil defense sirens to add to the spirit of the city council's proclamation. The baseball game ended at 9:50 p.m. Chicago time. Live telecasts and broadcasts from the dressing room of the victorious team were received for about 15 to 20 minutes immediately afterward. Then at 10:30, some forty minutes after the game had ended, the air raid alert signal went off. A steady blast for a full five minutes sounded, a signal which means that an air attack is possible but is not expected for least minutes. Prior to his sounding of the siren, the commissioner properly notified the police and fire departments, the public utilities, and all radio and television stations and newspapers. But only a very few minutes elapsed between the arrival of this notice and the sounding of the siren. Thus, the public had no warning of the event.”

The evocative titles used above are the chapter titles of the 1961 study for each of the alerts. One might summarize the causes of them even more succinctly as: “unidentified bombers,” “a crossed wire,” and “a guy who didn’t take his job seriously enough.” The different contexts are, as the authors of the study point out, both make it hard to come up with generalized responses, but also add a level of comparative contrast that is useful:

Here is an opportunity to seek parallels in social responses in three quite different situations, each laden with the warning of impending disaster. In Chicago, responsible officials were aware that the siren was sounded in a mood of carnival, but the citizenry could only guess a choice between celebration and catastrophe. In one case, we find government employees at work in the nation's capitol, civil defense instructions for identifying warning signals generally posted on the office walls, and supervisors and civil defense personnel assigned to the organization to structure interpretations and guide responses. In contrast, Oakland housewives were at home, their husbands at work, units of the basic primary groups ecologically segregated from one another. Chicago's experience is unique in that an urban community's enthusiasm for its baseball heroes had a large proportion of the population following the exploits of the athletes in a familial setting. Unlike Oakland, Chicago had its families clustered in primary group solidarity; unlike Washington, it had them removed from organizational constraints.

“The Occasion Instant” is what would be considered a pretty old-school anthropological/sociological study these days. Its main basis of data comes from surveys, completed some years after the fact, which it acknowledges is limiting. It does not use any significant statistical analysis for reporting its findings, and its interpretations are made through the psychological and sociological lenses that were in vogue at the time. So there are ways in which it feels like a very “dated” study in retrospect, something that would not pass muster (for both better and worse) in a modern academic context.

But it also tries to ask the big questions I mentioned earlier, because it was commissioned in the context of people actually caring how their population might respond during a nuclear attack and wanting to use this kind of study to give insights into what might be changed about nuclear communications. Which likely explains why the more recent study doesn’t ask these questions, and why there really isn’t that much research along lines at all — my sense from talking to colleagues is that this kind of thing has just not really been part of the “research agenda” of the post-Cold War social sciences, for better or worse.

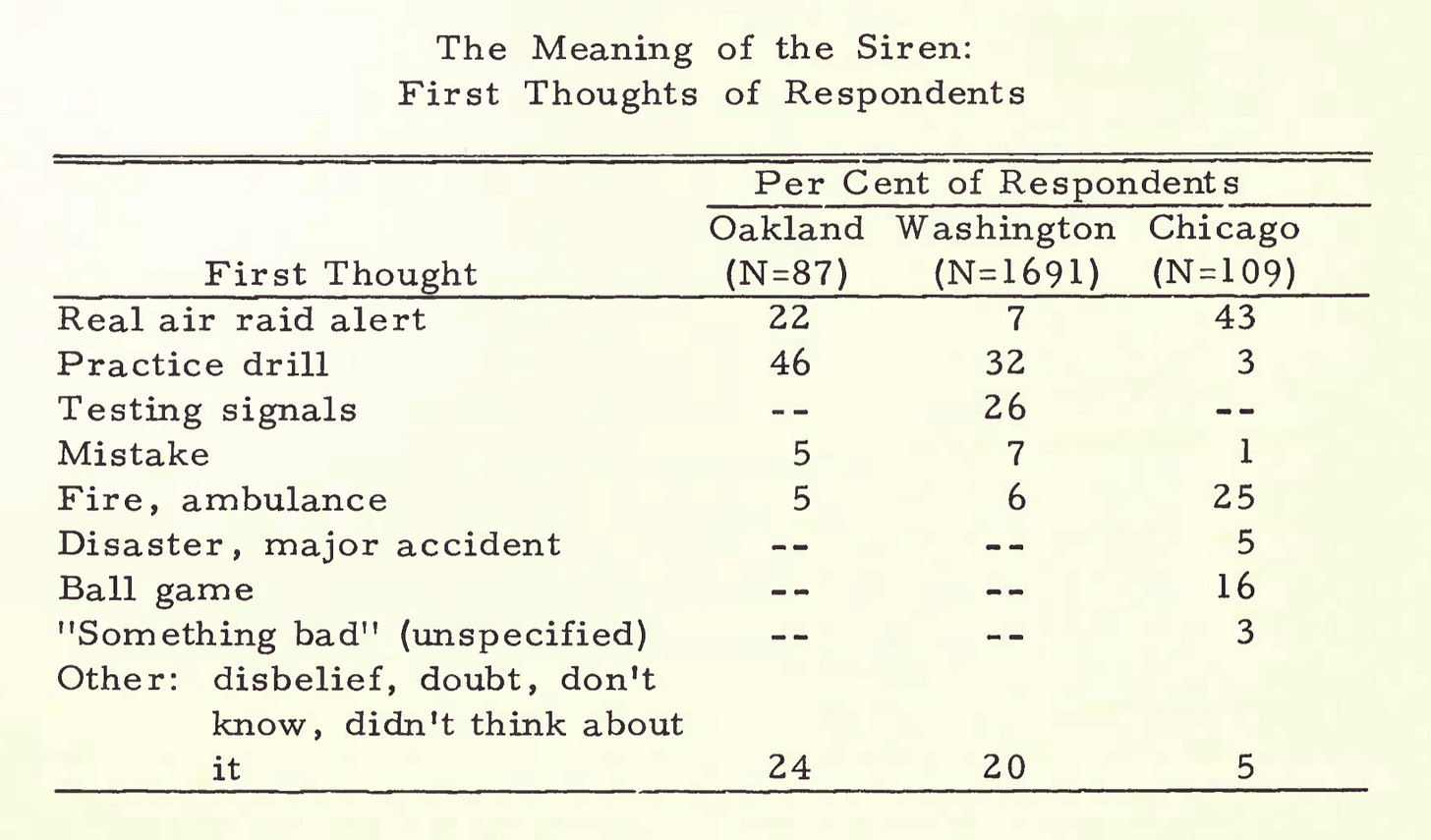

There were significant differences in the three cases between whether people believed the sirens were real. 43% of Chicagoeans surveyed thought it was a “real air raid alert,” but only 22% of Oaklandians did, and a mere 7% of Washingtonians. 3% of Chicagoeans thought it was “practice drill,” 25% misunderstood the sirens as being a fire alarm, and only 16% thought it might be associated with the ball game. In Oakland, 46% thought it was a practice drill. In Washington, 32% thought it was a practice drill, and 26% thought it was a test of the signaling system.

This is kind of striking. If I had been asked to guess, in the abstract, which city groups would take it more seriously, it probably would be the Washingtonians at the top (because of their governmental/”target” context), and Chicago at the bottom (because of the “ball game” context). And the low number by Oaklandians is also particularly interesting because it was the only one of the alerts that was actually meant to be an air raid alert — it was a false alarm, but not an accidentally or trivially triggered one. It was, in fact, a “real alert.”

Of course, one can make theories that fit the data. The Washingtonians, for example, were working in a context where practice drills and signal testing were common. The study found that many Washingtonians surveyed believed that the signal was only used for practice drills: “Clearly, these people have accidentally been so conditioned [by drills] as to render the signal used completely ineffective as a warning for a real attack. The same can be said for another 10% of the sample, who stated flatly that they ignore all warning messages that have not been previously announced.”

So what did people actually do? Very few actually took protective action of any sort, like going into a shelter. There is an interesting contrast between Chicago and Washington here. The Chicagoeans took it more seriously, but did not know what protective actions to take, and only 2% took any kind of action that “could be even loosely interpreted as protective.” In Washington, the number who took shelter was as high as 20%, which is large compared to Chicago but still remarkably low, especially because the Washingtonians actually did know what they were supposed to do and where they were supposed to go, as they were in federal buildings and drilled on it regularly.

Some people did nothing; they behaved as nothing unusual was happening, as if it were a nuisance to be ignored. The main action of people who actually did something was to seek more information about the signal. They tried to validate it — was it for real, or not? This meant turning to those around them if they were not alone, as well as turning on a radio or television if one was around. And a major predictor for how people with others responded depended on those around them: they took it as seriously as their immediate peers did.

How people responded, and how seriously they took the alert, correlated in complicated ways to various social categories. One of the most significant factors for determining who took it seriously was one’s “belief in the probability of war.” That is, if someone felt that war was unlikely because of a lack of “tension” in the “international situation,” then the signal could dismissed, and if you believed war was possible, then you took it seriously. This is the kind of logic that seems plausible but is quite fallacious: most people don’t actually have a great sense of the “international situation,” and have no idea what is happening on the other side of the world at the present moment.4

The study found that there was an interesting relationship between education and taking the signal seriously, but perhaps not an obvious one. Essentially, people who were “poorly educated” didn’t take the signal seriously; the authors concluded that they didn’t know what it was. But people with college educations were more likely to dismiss it than those with just high-school educations. The authors offered up two not-mutually-exclusive explanations for this. One is that the college-educated were “sophisticated and blasé enough to treat the siren cynically.” The other is worth quoting directly:

The higher the rank of an individual within a given social category, the more likely he is to interpret as invalid a signal intended to preface a disastrous situation. A plausible explanation of this is that persons who have achieved or enjoy high social status are less willing to entertain the possibility that a disaster could occur which would spoil everything.

That is, that the dismissal of the warning signal is a sort of psychological defensive mechanism meant to keep one from acknowledging the real possibility of losing everything one has — and those who have more may thus have more incentive to dismiss it. This is an idea that far transcends just nuclear alerts, and feels like it has real relevance in the present moment.

Another factor that was significant was gender: women tended to take the warning signal more seriously than men, and to report a stronger emotional response to it, and they also were more apt to seek out more information about it. The study’s authors suggested that this is because of their having a “generally lower status” than the men (and thus not falling into the defense mechanism posited above), as well as being “covered by a norm which allows them more expression of concern and fear for the well-being of others.” Men, in other words, are afraid of looking scared, and concerned.

They found that race did not prove to be a significant variable; any differences that existed in the raw comparisons disappeared when education was controlled for. They also found that people who lived in smaller towns, or had small-town backgrounds, were less likely to take the signal seriously than those who were living in cities.

And they found that the most significant variable with regards to age was that it was inversely correlated with taking the signal seriously — that is, the older they were, the less likely the citizens were to think the signal really meant a nuclear war was beginning. The authors weren’t sure exactly why that was, but surmised it might be a mix of the other factors (education, etc.), as well as the lack of understanding of the meaning of the signal, and, more speculatively: “Older people are more likely to hold traditional views and ideas, and full-scale nuclear destruction is not among them.”

Ultimately, the authors of “The Occasion Instant” appeared somewhat frustrated by the results. People received a signal that should have been understood to mean that they ought to take shelter. In many places, the people ignored it — believing it to be a drill. It was definitely not a drill in any case; again, in one case it was a “real” alert (Oakland), in another it was a mishap (Washington, DC), and in the other (Chicago) it was deliberately caused by a foolish official.

And even those people who did believe it was possibly real largely did not do very much about that fact, not because they were fatalistic, but because they didn’t know what to do. Which is its own failure.

The study authors lead the work with a line of argument that works well for this particular example as well as later hazards:

In ancient times or modern, social and cultural factors must be taken into account. A signal is not enough. It must have meaning in its cultural context. People must be taught its meaning so that they interpret the signal correctly and act upon it automatically. Society must be organized into groups and organizations which will help individuals interpret the signal and guide them to correct behavioral responses. The need to understand, predict, and control the social and cultural part of a total warning system is demonstrably imperative today for the survival of society.

“A signal is not enough” — this is, I think, what often gets misunderstood by many modern doomsayers as well.

What I think makes “The Occasion Instant” so interesting, despite its methodological weaknesses, is that it takes these “social and cultural factors” very seriously in its analysis. As they say elsewhere in it, the signal was heard, in that the technical equipment worked appropriately (except for, you know, the crossed wires), but that it failed to produce the appropriate human response. And that, I think, is a critique you could make of a lot of Cold War Civil Defense planning, and of a lot of attempts to get people to mobilize for various risks and causes today.

One thing that the study’s authors don’t get involved in is the question of how do you restore faith after a false alarm. Because that seems of some importance with both their examples, and the Hawaii one. Once you know that the emergency warning system has gone off inappropriately before, how do you avoid people assuming that the same thing has happened again if it goes off in the future?

What the officials in Hawaii did, along with promise it would never happen again and fix the (in retrospect, absurd) system they had in place that enabled it, was basically eliminate their ballistic missile warning preparedness altogether. That is, they came to the conclusion that another false alarm was a political risk, one that outstripped the risks that caused them to think they might need to warn their population about an incoming ballistic missile attack in the first place.

I’ve previously written up my own anecdotal observations on the Hawaii false alarm, based on a trip made to Hawaii in 2019: “Notes on the Hawaii false alarm, one year later,” Restricted Data (January 2019).

Sarah E. DeYoung, Jeannette N. Sutton, Ashley K. Farmer, David Neal, Katherine A. Nichols, “‘Death was not in the agenda for the day’: Emotions, behavioral reactions, and perceptions in response to the 2018 Hawaii Wireless Emergency Alert,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 36 (May 2019), doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101078.

Raymond W. Mack and George W. Baker, “The Occasion Instant: The Structure of Social Responses to Unanticipated Air Raid Warnings,” Disaster Study 15, Disaster Research Group, National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council publication 945 (Washington, DC, 1961).

As an aside, I heard this sentiment from some people in Hawaii regarding the 2018 false alarm, and I always want to quiz them: Do you know what time it is in Pyongyang, right now? Because if you don’t know that — and almost nobody did, a fact not helped by the fact that North Korea used an eccentric off-by-half-an-hour time zone up from 2015 until April 2018 — then how can you possibly know what did or didn’t just happen at, say, the DMZ? Or at a North Korean test range? Or if the North Koreans believed, wrongly or rightly, that the United States had just tried to assassinate their Dear Leader? (In the 1950s one could say much the same things about Berlin, the Kremlin, and so on.) On what basis would it be in any way rational to bet your life on the idea that because you occasionally keep up with the international news, that you could be so confidant, so smug as to dismiss an imminent warning? Or that it was worth dying in order to not be embarrassed later if it turned out to be false? But I digress.

I suspect that I would also not react if an alarm like that went off. I live in a decidedly third tier American city, but there is a large defense contractor presence here. So if nuclear war were to come, I am not sure I would want to survive the first blast only to die of second order effects in the weeks or months ahead. Since I am not in one of the first tier cities, who concieveably would be the more likely victims of more limited engagements, and therefore could concieveably be helped out by the remaining civil society, I just don't see the point.

And I do always leave the building when the fire alarm goes off, and I always evacuate for severe hurricanes. So it is not that I ignore all warnings. I just don't see much utility in reacting to a warning of a nuclear attack.

Two things. I grew up in the 60s and 70s a few miles from Whiteman AFB. We knew that the base and the silos scattered around the area weee all first-strike targets. Had the sirens gone off, I don't know that we would have done anything. What do you do when you expect megaton warheads to explode just outside of your small town?

I wonder what would happen now, as we are getting more and more use of AI to answer questions and summarize news, to people looking for information on the situation and how to respond? What role would hallucinating AIs take?