Welcome to DOOMSDAY MACHINES

Post-apocalyptic Road Trips, End of the World-building, and Interesting Times

Welcome to Doomsday Machines, a Substack newsletter/blog about the post-apocalyptic imagination in fact and fiction.

Doomsday Machines will have a weekly post in one of the following categories, each of which are designated as separate sub-newsletters:

Post-Apocalyptic Road Trips: Discussions of self-consciously fictional media (novels, films, games, etc.) portraying post-apocalyptic worlds, analyzed for their themes, tropes, and historical context.

Interesting Times: Profiles and analysis of historical documents, events, plans, and so on, relating to apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic conditions, which are not self-consciously fictional (however “imaginary” or “unreal” they may be). For example, discussions of US government nuclear war plans, or nuclear war survival plans.

End of the World-Building: Posts related to the development of the Oregon Road ‘83 post-apocalyptic video game, ranging from things that are very strictly in the category of “game design,” as well as things that are really about creating a coherent conception of the underlying world of the game.

Doominations: Conversations between me and various smart, interesting people I’ve met over the years who generally think about some aspects of the end of the world for a living. You know, as one does. (Paid subscribers will receive access to the audio — and video, when available — of the unabridged conversations as a bonus podcast.)

There will also be Mutually Assured Distractions (brief posts on interesting imagery — post-apocalyptic Pinterest) sprinkled in along with these regular sections.

If all of that becomes too overwhelming, you can turn on or off your subscriptions to any one part of the blog by going to the newsletters page. But I think you should give them all a try first, even if you suspect some parts might be more interesting to you than others — they’re all part of a coherent whole.

Who am I?

I’m Alex Wellerstein, and I’ll be writing most of the posts here, and editing/curating any guest posts. I’m a historian of nuclear weapons with a PhD in the History of Science.

I am a professor in the Science and Technology Studies program at the Stevens Institute of Technology, an engineering school in Hoboken, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from Manhattan. I teach courses on the history of science, among other topics of interest to me.

I am the author of Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States (University of Chicago Press, 2021), and have written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Harper’s Magazine, among other popular and scholarly venues.

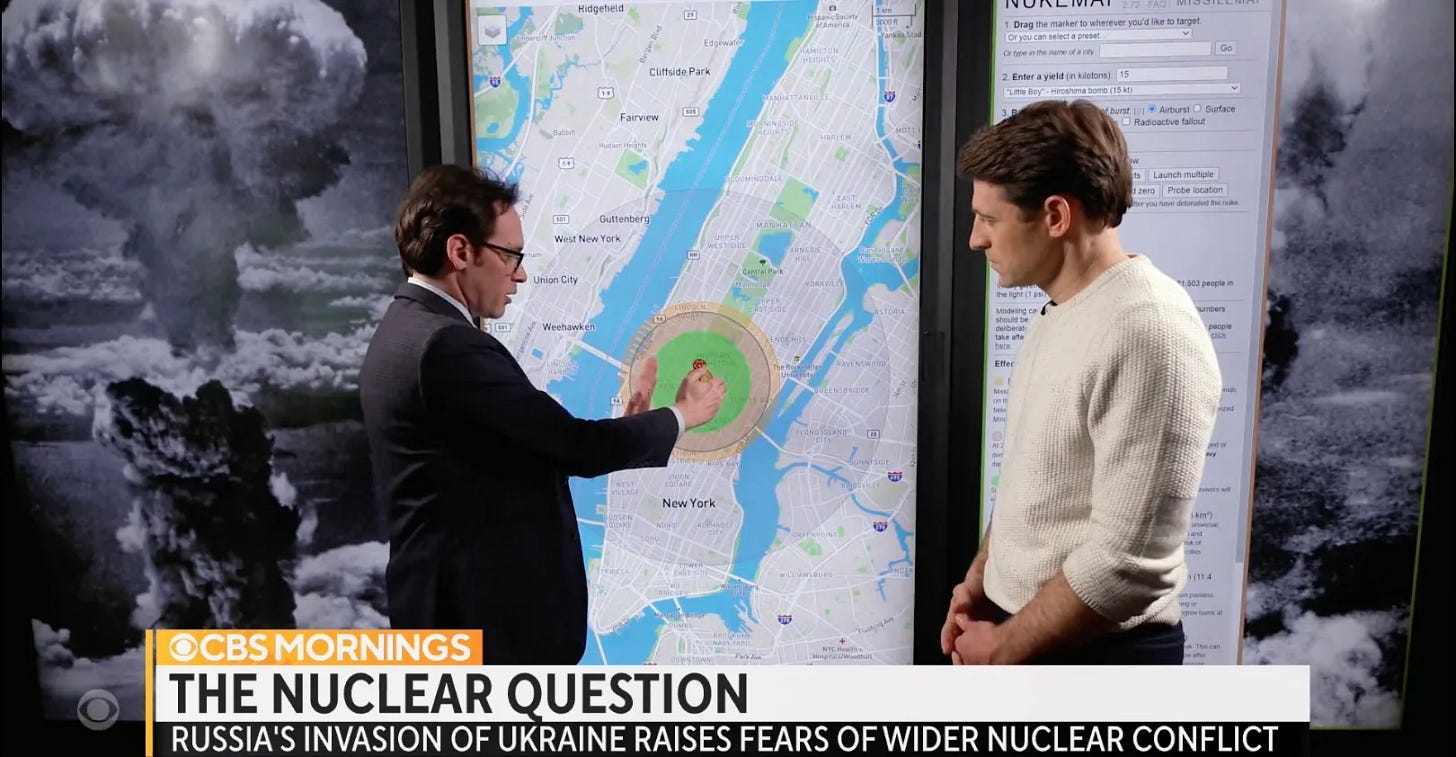

I’m also a computer programmer with experience in graphic design, web development, and database design. I’m the creator of the NUKEMAP. I’m working on a number of other digital projects right now, including a post-apocalyptic video game and an open-source nuclear war simulator. All of which will have their places on Doomsday Machines, and the work on which is what inspired me to create it.

I’m also in the process of writing my second book (on Harry Truman and nuclear weapons), set to come out in summer 2025 from HarperCollins.

You can read more about me on my personal webpage, if you want.

Why do this at all?

This started out as a vague idea about making a development blog (devblog) for the post-apocalyptic video game I have been working on for several years (Oregon Road ‘83). But as I started sketching out the kinds of topics that could be covered by such a thing, I realized I had a lot more to say that any mere devblog really justified, and that the very idea of writing up a bunch of relatively small pieces of this sort really jazzed me up. I was talking my ideas over with Andy Adams, and he mentioned Substack as a possibility. I thought that sounded like something worth exploring, and here we are.

I have another blog, Restricted Data: A Nuclear History Blog, which I’ve kept going (less over time) since 2011. I’m still planning on posting things there, occasionally, but the genre of that blog is quite different from what I’m imagining this one to be, and over time the posts I’ve written on there have tended to be much longer, more ruminative, more “serious history,” and so on. Which is good and fine. But I think I’ve felt weighed down by it over time. Doomsday Machines feels like an excuse to “reinvent” my online writing, collaborate with some interesting people (and students), and the whole thing has me energized and excited.

Why “Doomsday Machines”?

Coming up with a good name for something like this proved quite difficult. There are a lot of possible names out there. I asked a lot of people for suggestions, and got some good ones, but nothing that clicked. I realized that I wanted something that was immediately legible, was simple and easy to remember, was a twist on an already-familiar phrase, and encompassed the wide variety of content that I wanted to write about — not just nukes, not just fiction, not just history, but “all of the above.”

So when Doomsday Machines popped into my head while on a long car trip, it immediately grabbed me. It checked all of the boxes above.

A singular “Doomsday Machine” is already an interesting idea, à la Dr. Strangelove and Herman Kahn: an end-of-the-world invention, a gigantic bomb, or even just an evocative term for the entire apparatus that is required to make nuclear war a credible, realistic possibility.

But making it plural gave it that little twist, and provokes so many immediate questions! What machines are we talking about? Are we talking about the nuclear weapons themselves? The nuclear arsenals of the world? The states and the weapons complexes which produce them? The scientists, the technicians, the soldiers, or the politicians whose efforts make them real?

Or could it refer it to the popular imagery (including Dr. Strangelove) that has shaped how we think about these weapons and threats over the decades? What about the creators of the novels, films, songs, paintings, or games that shape our understanding of possible Doomsdays? What about the consumers of such media?

Or are we all Doomsday Machines, to one degree or another? Are we not all, in our own little ways, contributing towards an endless march towards extinction, in the same way that our individual lives all march towards death?

Could be, could be! In short, the name seemed to encompass everything this newsletter was going to be about.

The only reservation I had was that the late Daniel Ellsberg, who I knew, had published The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner in 2017. Was it too close of an association? I decided it is not, as the titles are different-enough when taken as a whole that I don’t think anyone will get confused that they’re the same “product,” and the term “Doomsday Machine” is sufficiently “generic” that dozens of books carry it in their title.

But if you are confused, let me be clear that this site is not the same thing as Dan’s book, at all. They both take their cue from Dr. Strangelove and Herman Kahn, and they both involve discussions of nuclear weapons and nuclear war, but Dan’s book is mostly a memoir of his own (fascinating and important) experiences, and this is going to be a cornucopia of topics. If you find this blog interesting, you would also find Dan’s book interesting and worth a read, but they are not connected in any way.

What is your subscription model? Do I have to pay? What do I get if I do pay?

Assuming no major and unanticipated change in circumstances, the main content of the site will always be provided free and without any paywall.

Paid subscriptions are available, however, as a means for people to give some “extra support” to this site and its contributors.

Paid subscribers will also get access to two “paid-only” things:

The full podcast audio (and video, when available) of any interviews that are part of the Doominations conversation series.

Access to Wellerstein’s Weekly Wasteland Wrap-up, a very informal newsletter of miscellaneous thoughts, ideas, updates, news, links, images, media, whatever, that I came across that week and thought was interesting-enough to share with other people. Think of it as as a throwback to what blogging used to be in its early days.

The monthly paid subscription rate is the lowest that Substack allows me to set it to, and I’ve set the annual rate to 50% of that. If you are dying to see the paid content and would find it to be a financial burden, just get in touch with me.

There is also an additional tier, called the Interesting Times Gang, where people can give more money for an annual subscription, just to be extra supportive.1 These generous souls will get all of the above plus a special and unique (physical) thank-you gifts once per year.

There is absolutely no expectation that people will become paid subscribers, and no pressure to do so. The above extras are offered up as a means of a “thank you” for supporting the site, and are not offered up as “products” that you will be “buying” (and the higher expectations of quality that might come with that approach — though I am a perfectionist and a workaholic, so they won’t be slapped together). Think of them as an attempt to balance out my own aversion to reading or writing paywalled content, with my desire to feel like anyone who did want to pay for content ought to get something for it.

Money from paid subscriptions will be used to offset any development costs (like the software subscription needed for recording and transcribing conversations and the costs incurred in acquiring obscure and out of print media), and, hopefully, to allow me to compensate people who write for the project for their contributions.2

If you’re not a subscriber, you can subscribe using the button below.

And remember that the whole point of a Doomsday Machine is lost if you keep it a secret! So if you end up enjoying it, make sure to tell the world, eh!?

“Interesting Times Gang” is an homage to Iain M. Banks’ sci-fi novel Excession, where it applies to a group of hyper-intelligent machine intelligences who are part an informal, secret group that keeps an eye out for civilization-scale threats. I have always wanted to use it for something, and this seemed appropriate.

This is a labor of love and I suspect it is not likely to make any actual profit. I am assuming that anyone who writes for me is similarly willing to volunteer their time to the project because they think it is interesting, fun, and maybe important. If you are interested in writing something for Doomsday Machines, you can get in touch, but the odds are very low I will take you up on it unless you’re someone I already know personally, because I don’t like the idea of exploiting strangers. If you have ideas for something that somebody else should write, by all means, send them as e-mails, comments, what have you!

A fine recent UK-flavoured post-apocalypse -- swarm of comet/meteor strikes, decades of rising sea level and global rain) is 'The Aftermath' : Shelter, by Dave Hutchinson (2018); Haven, by Adam Roberts (2018); and Sanctuary, Hutchinson, 2023.