"Where black is the color, where none is the number"

Bob Dylan's dark, gnomic, and adaptable post-apocalyptic masterpiece

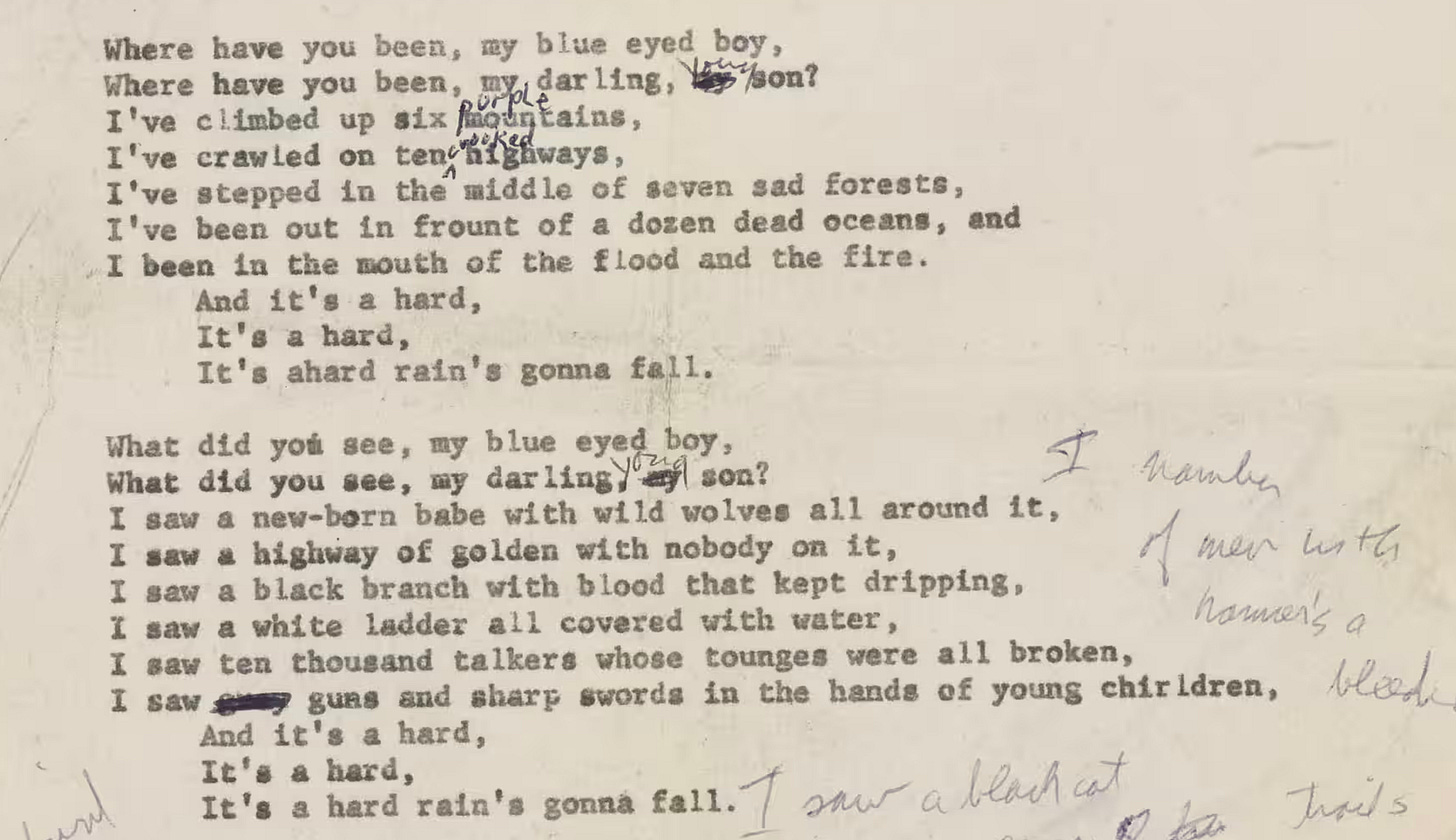

Last week I wrote about one of Bob Dylan’s lesser-known songs about nuclear war: “Let Me Die in My Footsteps,” which articulates an argument against fallout shelters. The song was cut from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), but the album contained a much darker, more mysterious song that can be plausibly interpreted as “post-apocalyptic”: “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

The nearly seven-minute song is far less straightforward than “Let Me Die in My Footsteps,” which feels trivially literal by comparison. “A Hard Rain” follows a fairly simple, repetitive pattern, in which one voice asks another where he has been, what he has seen, what he has heard, who he met, and what he’ll do now. And the meat of it is in the replies, each of which are fragments of a dark world:

Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, where have you been, my darling young one?

I’ve stumbled on the side of twelve misty mountains

I’ve walked and I’ve crawled on six crooked highways

I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests

I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans

I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard

And it’s a hard,

and it’s a hard,

it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fallOh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what did you see, my darling young one?

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’

I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’

I saw a white ladder all covered with water

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

And it’s a hard,

and it’s a hard,

it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

If the structure of the song, musically, feels oddly old-fashioned, it’s not a coincidence. It is based directly on the Anglo-Saxon ballad “Lord Randall” (dating from at least the 17th century, but has a distinctly medieval feel to it), which has the same call-and-response format. “Lord Randall” is fascinating and worth a full listen by itself. Of the many versions on YouTube, my favorite is this one, and it helpfully has the lyrics displayed:

“Lord Randall,” like “A Hard Rain,” is a dark ballad, but unlike “A Hard Rain,” it tells a single, evolving story, one that gets darker and darker as the song continues. “A Hard Rain” starts dark and lacks any kind of real progressive narrative; it is not telling a story, it is describing a world, of sorts, albeit from different perceptions (where you’ve been, what you saw,

What is “A Hard Rain” really about? It’s been often argued that it is about nuclear war (with the missiles or the fallout being the “hard rain”) or the Cuban Missile Crisis. Dylan himself has always pushed back on this, insisting that while it contains allegories and metaphors, it is not in response to a single thing or event, or even depicting a single thing or event, and that the allegories/metaphors are pretty hard to parse. He wrote it prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis, in any event.

Whenever I listen to “Hard Rain” — which is fairly often, I admit — I am always drawn to the evocative imagery of individual lines, as opposed to it adding up to a coherent whole. Each “image” makes for a bold and dark statement, self-contained and horrible in its own way. Many of them feel ripped straight out of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, though of course if there is any influence it is the other way around. And like The Road, its lack of specificity of allows it to be fit and interpreted in a wide variety of possible “worlds” — including, of course, the idea that it is just a description of our current world, just in veiled imagery. Perhaps we’re already in the post-apocalypse.

When working on scenes for the Oregon Road ‘83 video game, I’ve often thought about trying to use these lines as writing prompts, imagining how one would integrate them into a “grounded” view of the post-apocalypse:

I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans

I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

Heard one person starve, I heard many people laughin’

Heard the sound of a clown who cried in the alley

I met a young child beside a dead pony

I met a white man who walked a black dog

I met a young woman whose body was burning

I met one man who was wounded in love

I met another man who was wounded with hatred

Where the people are many and their hands are all empty

Where black is the color, where none is the number

I’ve known for a long time that I’m not someone who gets a lot of out poetry, despite occasionally having read it. Most of it does very little for me. I don’t know what that says about me, but despite this, I have come to learn to respect that a good poet can create a sentence that, despite being simple and spare and short, can evoke a tremendous emotional response. The right words in the right order, I often tell (STEM) students who are unsure whether they should put effort into being better writers, is like code you are injecting into peoples’ brains, and if well-done can trigger immensely powerful ideas. It might be one specific idea, or it might be vague-enough that every listener has the opportunity to make their own meaning from it, to resonate with it (or not) in their own way.

“Where black is the color, where none is the number” is a statement about the aesthetics of absence, both as a literal representation and a feeling — that infinite emptiness opens up inside of one, when those dark and melancholy thoughts settle upon one. Churchill called this feeling “The Black Dog,” and this is also what comes to my mind when I hear “I met a white man who walked a black dog."

In December 2016, Bob Dylan was (controversially) awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He didn’t go to the public ceremony (as is his wont), and in his stead Patti Smith performed an “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” It’s an emotional and complicated performance, including a difficult moment in the beginning in which she freezes up and has to restart it. But that humanizes it far more than a more polished performance might:

At the time, this felt like a dirge, a funeral march, and a portent, coming right after the disastrous election of 2016. The context felt like it turned the song into an expression of mourning — which is not what I hear when I hear Dylan, then a young man of only 21 or so, singing it on the original recording. But I get the sense that Smith chose it also because if any song of Dylan’s is to stand in for his worthiness for a Nobel Prize in Literature, “A Hard Rain” is a pretty solid candidate.

I’ve seen some interviews where Dylan explained what he meant by a line or two of “A Hard Rain,” and, frankly, it’s not as interesting as I’d like it to be. This doesn’t take away from the final product, for me, or its impact. Dylan was not, here, trying to communicate some kind of “message” in the same way that “Let Me Die in My Footsteps” or “Blowing in the Wind” could be construed as trying to do. As young people today might say, it’s mostly a song about vibes, evoking images and associations that the listener processes according to their own circumstances and concerns. It is not a song about the 2016, or 2024, American election results. And yet, the best art transcends the specific intentions of the artist, perhaps, and the best poetry captures something in language that feels so perfectly apt as a deeper description of the world, or of our feelings, that one can understand why poets of old believed such insights must be divinely inspired.

The last verse of “A Hard Rain,” when the traveler is asked what they will do next, offers up different kind of resolution than “Lord Randall” does, though: a future. The traveler will go back into the world, “Where the people are many and their hands are all empty / Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters / Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison / Where the executioner’s face is always well hidden,” and so on. The world is still the world it is; it is still dark and ugly and perhaps ruined. There’s no sugar-coating it.

But even in this world, the traveler — the poet — has a role:

And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it

When I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

That’s not exactly hope. But it is survival, and it is purpose. And that’s more than simply a world of black and nothingness.

Have you read Byron's "Darkness"? He wrote it in 1816 ("The Year Without a Summer" - which also gave us "Frankenstein" - now that was an influential year and problematic artistic polycule if there ever was one, but I digress), but it's striking how much imagery it shares with Dylan's and McCarthy, or rather how much of modern post-apocalyptic language echoes Romantic poetry.

---

"Darkness"

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chill'd into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires—and the thrones,

The palaces of crowned kings—the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum'd,

And men were gather'd round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other's face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain'd;

Forests were set on fire—but hour by hour

They fell and faded—and the crackling trunks

Extinguish'd with a crash—and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil'd;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and look'd up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past world; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnash'd their teeth and howl'd: the wild birds shriek'd

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl'd

And twin'd themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless—they were slain for food.

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again: a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left;

All earth was but one thought—and that was death

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails—men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devour'd,

Even dogs assail'd their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famish'd men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lur'd their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answer'd not with a caress—he died.

The crowd was famish'd by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies: they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heap'd a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they rak'd up,

And shivering scrap'd with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other's aspects—saw, and shriek'd, and died—

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend. The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless—

A lump of death—a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirr'd within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp'd

They slept on the abyss without a surge—

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before;

The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish'd; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them—She was the Universe.

Alex, eight years ago you talked to us on the day after the election and gave us, not comfort, exactly, but a sense of community. We're in this together. This post has the same feel. I just listened to Patti Smith singing "Hard Rain" at the Nobel ceremony and it felt cathartic. Thanks buddy