You too can survive a nuclear war — if you have a flying car

The essential contradictions of Dean Ing’s Survivalist novel “Pulling Through” (1983)

The author Dean Ing (1931-2020) was, by all accounts, an unusual character. He was in that odd circle of right-wing, pro-military, high-tech advocates of the late 1970s and early 1980s, like his friend and occasional co-author Jerry Pournelle, who seemed, in the early Reagan era, to be on the forefront of some kind of space-based vision of the late Cold War. He appears to have felt that writing pot boiler thrillers was a means to an end, a way to package a diatribe in a more palatable, and profitable, package.

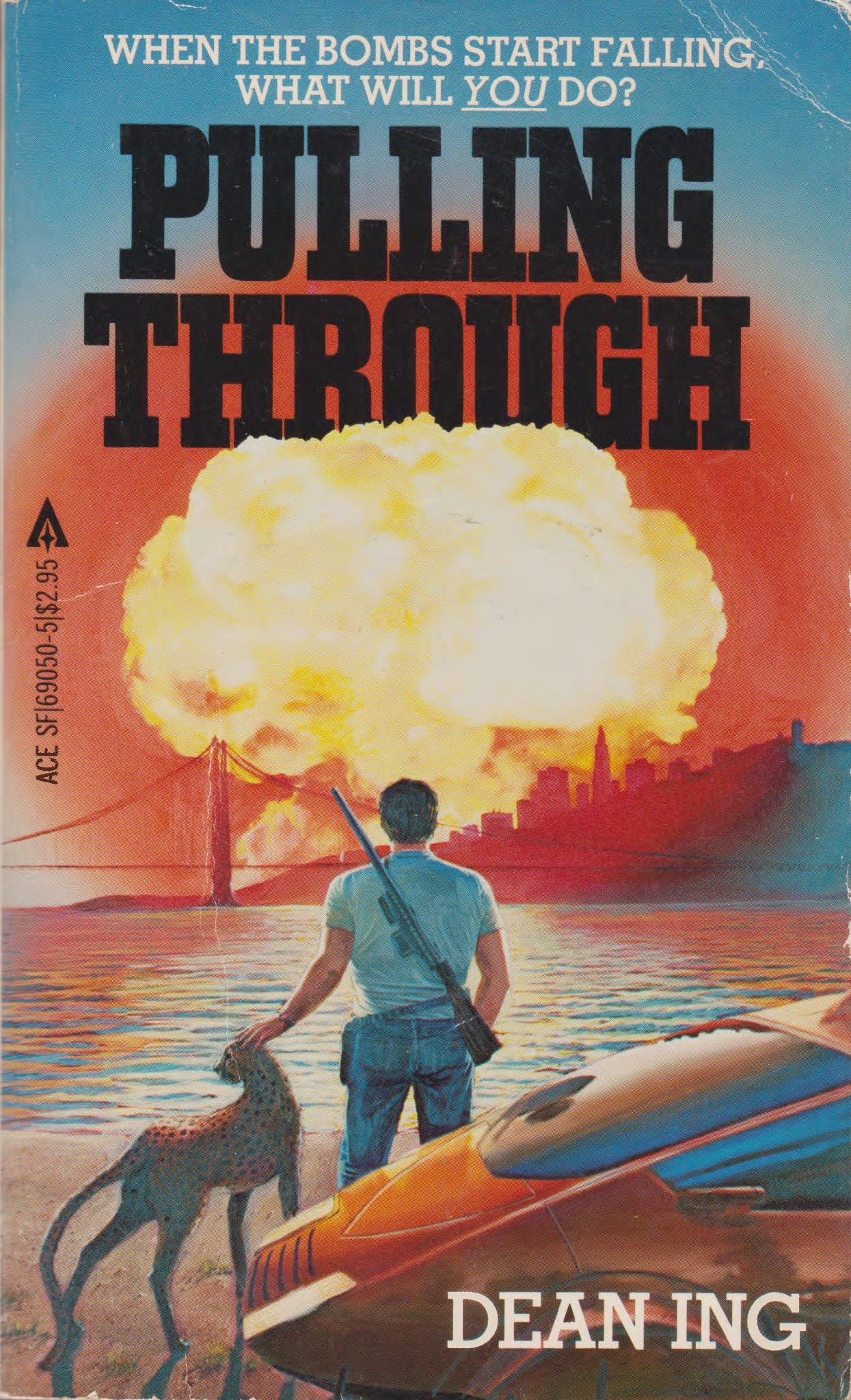

My interest in Ing is the “Survivalist” novel he published in 1983, Pulling Through. This is, let us be clear, a bad book. But it is amazing as an historical artifact, in its own way. Let us just spend a moment luxuriating in this amazing cover that might seem like parody but is decisively not:

You might recognize the art — it is one of the banners I use for Doomsday Machines, because the moment I saw it, I thought, wow, this really encapsulates… something… about the post-apocalyptic imagination.

Pulling Through is a story told from the point of view of one Harve Rackham, described pithily on the back cover as:

HARVE RACKHAM, bounty hunter, race-car driver. His best friend is a hunting cheetah. Harve has turned his California home into a survival shelter. He intends to pull through.

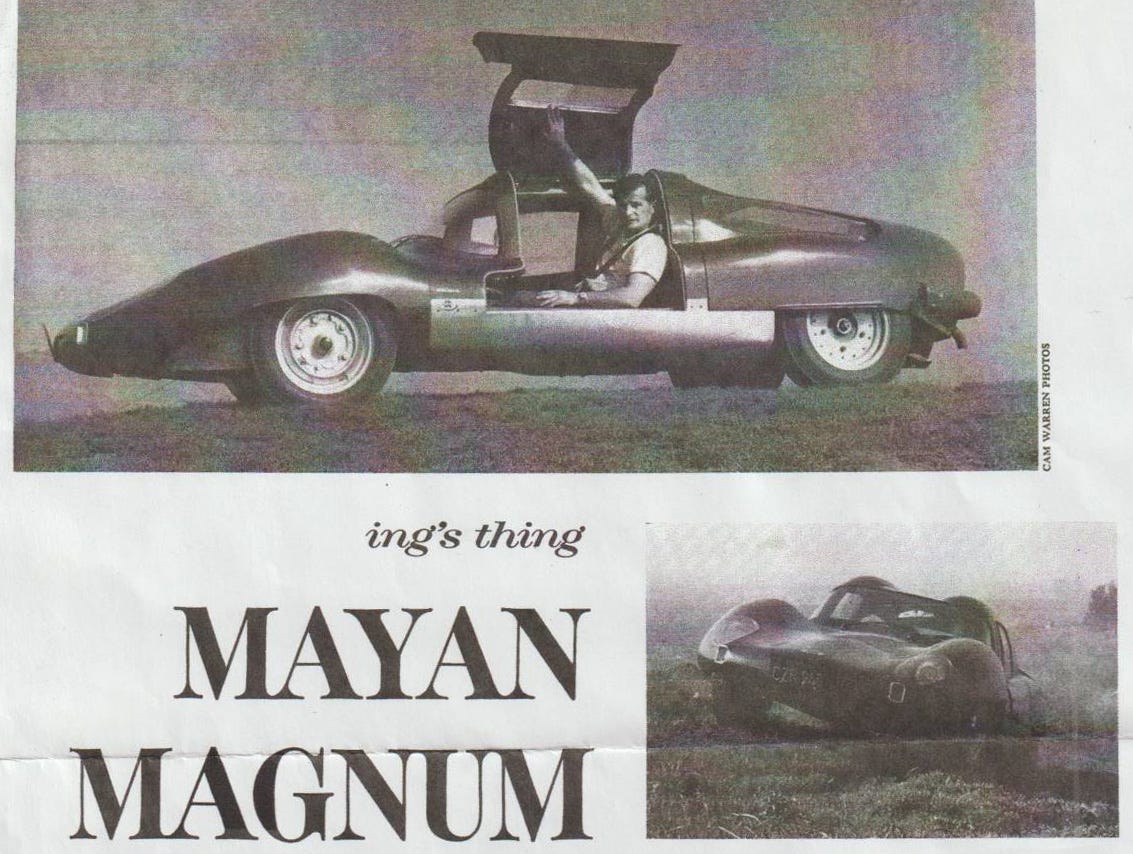

So that’s Harve on the cover: tall, well-armed, with his pet cheetah (Spot), and his race car. I would note that this is not just any race car: it is a (fictional) Lotus Cellular, a super-lightweight, two-seater, high-performance race car that uses “air-cushion fans” to “hop” over fences, other cars, and barriers, and can even (briefly) hover over water. More on that, and the cheetah, in a minute.

What is Harve “pulling through”? Nuclear war, of course. Ing never says when the novel is set, but the context at times suggests we are talking about something that is meant to be “near future,” a world almost identical to the early 1980s, except for the presence of “hopping” race cars, a much larger degree of nuclear proliferation, and occasional mentions of things like “holovision.”

Harve lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, although not in the most urban parts of it. The fact that the cover shows Harve watching, without any apparent dismay, San Francisco getting nuked is, well, very telling about the overall ideology of this novel. Harve sheds no tears about true urbanites (much less effete San Franciscans) in this book; he has really nothing but scorn for them. The actual scene shown in the cover never happens in the book (Harve doesn’t see the nuclear detonations, because he’s already back at home when it happens), but it certainly captures something about the smug satisfaction that people who write under the “Survivalist” (and later “Prepper”) mindsets tend to have about cities and their inhabitants.

Harve comes off as a temperamental loner, but he’s not actually alone. With him on this journey are, as the back cover summarizes, his sister and brother-in-law:

SHAR McKAY, Harve’s little sister. Shar’s latest fad is nuclear survival. She intends for her husband and kids to all pull through.

ERNEST McKAY, engineer. He has the knowledge and skills to save his family. With his help they’ll all pull through.

Shar’s role in the story is mainly as the source of Harve’s knowledge about prepping, which is an interesting narrative choice. Ing could have just made Harve the prepper, right? But having the sister be the one who took a class in prepping appears to give Harve some “everyman” cover. Of course, the fact that he’s a bounty hunter with a cheetah and a flying race car undermines that a bit.

Ernest’s role in their “survival” is extremely substantial. Throughout the days after the attack, Ernest is the one who proposes all sorts of homemade engineering solutions to problems that arise, like a lack of sufficient air in the basement requiring a home-made air pump. Without Ernest, they’d all be dead — which begs the question of how survivable nuclear war is, if you don’t happen to have an engineer lying around. We’ll come back to this issue.

Shar and Ernest’s kids are Cammie and Lance. Cammie does pretty much nothing other than be cheery and helpful (like Shar and Ernest) and a model “survival” child. Oh, and she assumes, early on, that Kate is Harve’s girlfriend, and refers to Kate as his “little flesh,” which is treated as “high-school jargon.” Ick.

Lance, on the other hand, is a foil: he’s the spoiled modern child who has never been told “no” and thus lacks the discipline necessary to survive under life-or-death conditions. Shar and Harve talk about this, and how their parents were much harsher on rebel Harve, but it taught Harve character and resolve. So we get a little “these kids/parents today” moralizing in this book, too.

Since I do not recommend that you go out and read this book — and it is all just as obvious as it can be — I’ll spoil it for you and tell you that Lance’s lack of discipline results in him not “pulling through.” Sorry, Lance. This doesn’t seem to eat Harve up too much, though, and neither does the thought of millions of other people not “pulling through.”

How many millions? At the end of the book, Harve says that 80 million Americans survived the nuclear war. So assuming a pre-war population of around 230 million Americans, that means that around 150 million Americans died, a whopping 66% death toll.1

There are a few other characters who show up, the most important (and back-cover worthy) being Kate:

KATE GALLO, runaway, forger, a tough street survivor. She’s trouble—but when real troubles come down, Kate will always pull through.

I showed this to a colleague who immediately said, “Oh, I bet she’s good looking, too, right?” Right. A fact that Ing/Harve tells us every time she is mentioned. Kate “looked smaller than eighteen,” but “also older.” She was a former “teen model.” She got into Harve’s car “with a goodly flash of leg.” She was a “tough bimbo.”

Kate had been “raised in a strict household where females were expected to keep the Sabbath holy, the pasta tender, and the men on pedestals,” and “had learned too much about the rest of the world; had cast aside her illusions and her virginity before reflecting that both had their good points; had decided she would make the system pay.” More like Dean Ick, am I right? (I’ll be here all week, folks.)

Kate is the only character here who gets a character arc: she starts out as a criminal, a bounty that Harve is taking in, but when the war starts, in a fit of pure generosity Harve allows her to switch from being cargo to a bonafide family member. She is appropriately wary of this for about five minutes, and initially resists allowing Harve to boss her around, but after he mansplains to her that his bossing her around is just about what is necessary to survive, she immediately falls into line as a submissive survivalist.

By the end, of course, “kissable Kate” has fallen in love with brave ol’ Harve, and has become the “reward” (along with surviving) for all of his efforts. Gosh, who could have seen that coming? What writing!

Harve himself changes not one whit over the course of the book, except that he loses weight. You see, he had once been a tall, trim, fit man, but the excesses of modern society had caused him to gain some weight, and so he spends most of the novel fat-shaming himself and complaining at how out of shape he had become. But the apocalypse diet turns out to be just what he needs, and over a few days (!) he drops a few pant sizes. This allows Kate to tell him at the end that, yes, she appreciates that he looks great (of course), but that the real appeal is his survival instincts:2

"Very few men realize how much a woman will do for a man she can depend on. Long legs and a tight gut are nice, but give me a man I can depend on. Fortunately I can have it all unless you start eating too much again." And then she found my mouth and used it mercilessly, I'm happy to say.

If you’re suddenly struck by nausea, you might check your Geiger counter, but it’s probably the writing. I fully agree that “life goes on” even after major disasters, but jeez, does this feel like a tone-deaf way to talk about the aftermath of a nuclear war.

So, about that war. The exact circumstances are left somewhat murky and deliberately complicated and “near-futurish”:

Syria's cruise birds were Soviet-made; her nukes probably Libyan. It no longer mattered whether the Soviets had known that Syria could screw nuclear tips onto those weapons. Far more important was the battle raging between our Sixth Fleet and the fast Soviet hoverships we had engaged as they poured from the Black Sea into the Aegean. I figured the [USS] Nimitz for a supercasualty, and I was right; once the Navy lost that big vulnerable beauty they'd be shooting at everything that moved.

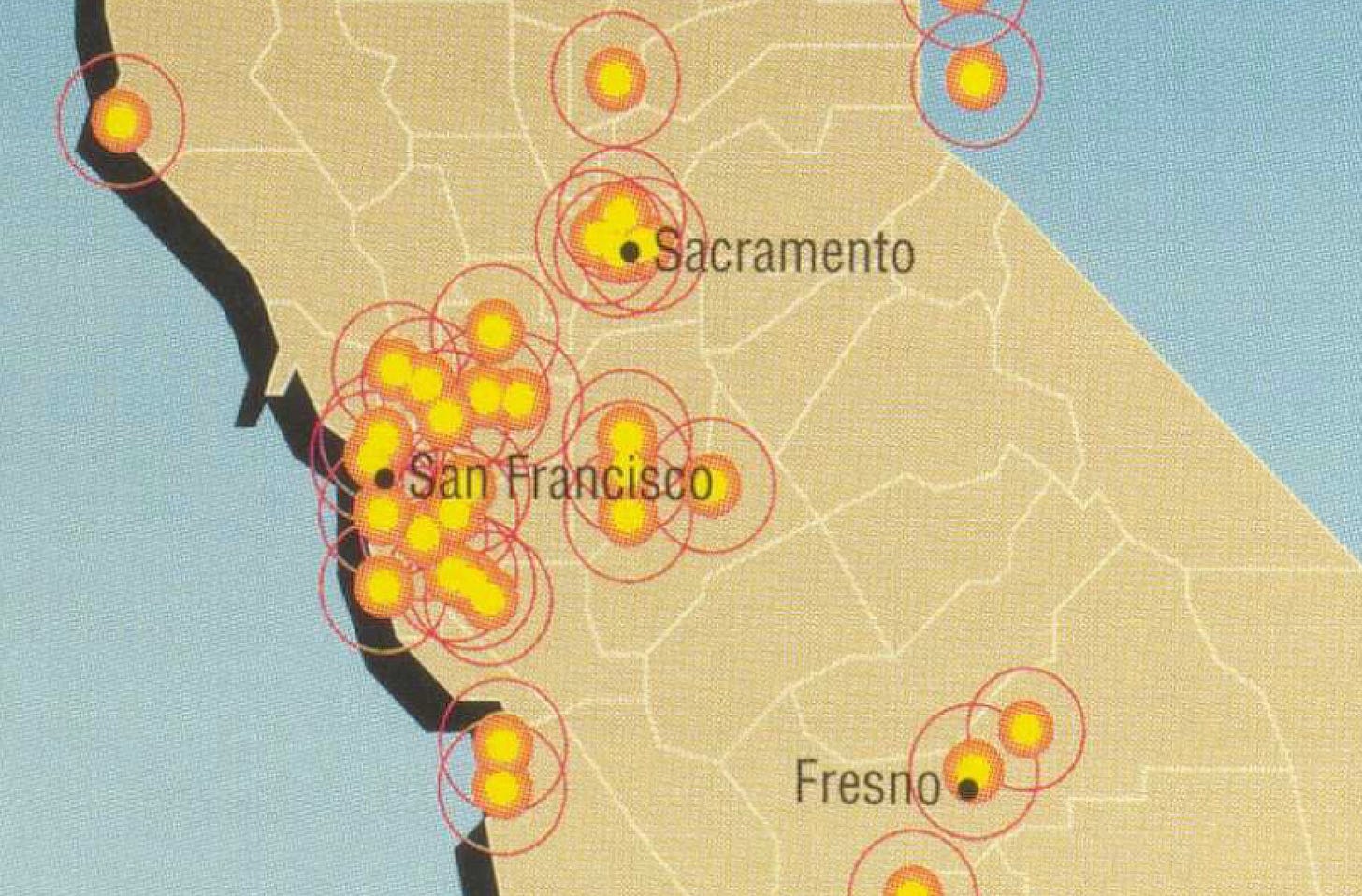

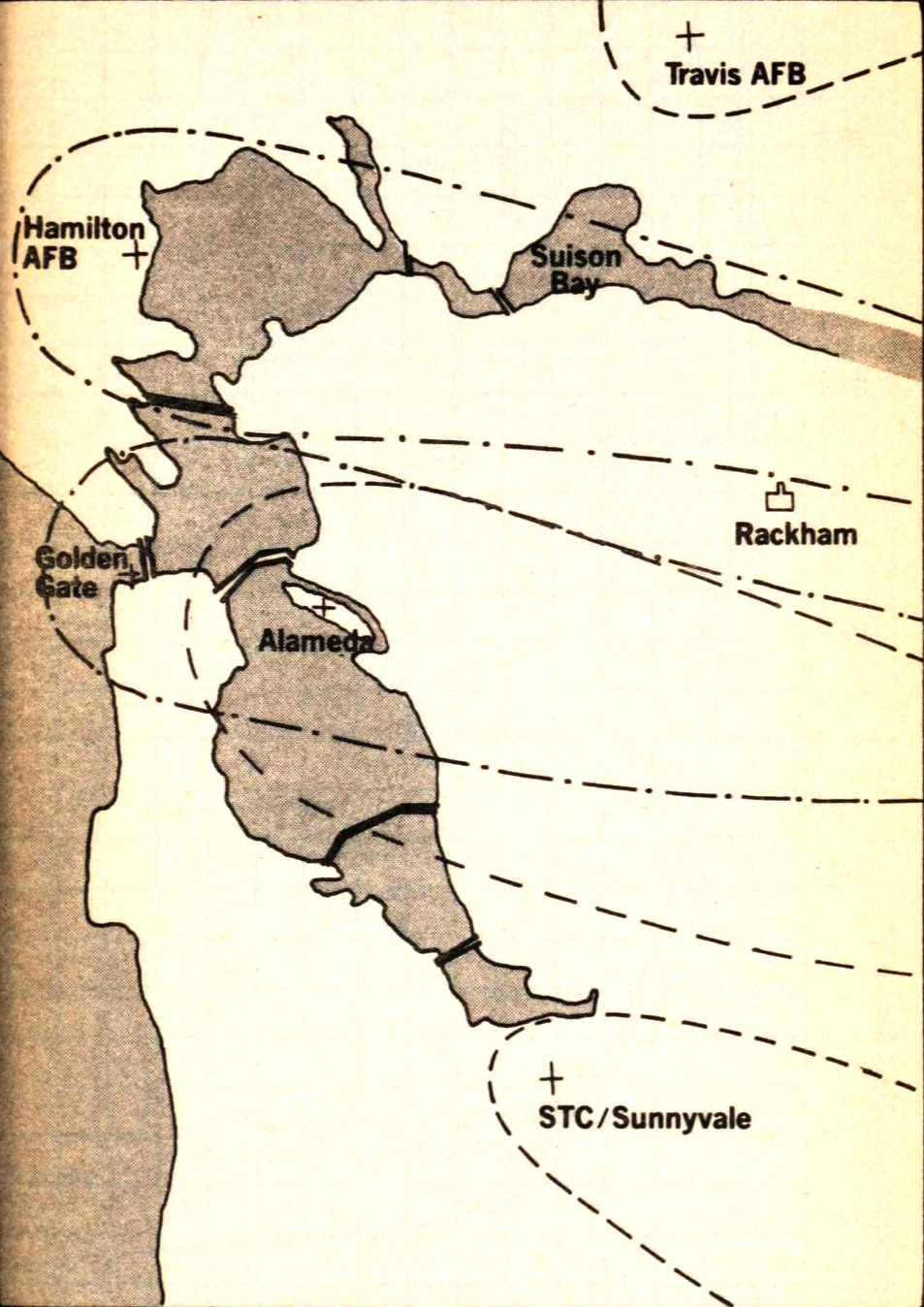

So some kind of Middle Eastern escalation leads to a slug-fest between the USA and the USSR, and the Bay Area where Harve lives gets a few direct hits from Soviet missiles. The book contains a map on the inside cover, showing the ground zeros, the fallout plumes, and Harve’s location:

I would note that this is a pretty optimistic targeting plan for 1983, one that assumes one-nuke per target, and not really that many targets. William M. Arkin and Richard W. Fieldhouse’s 1985 Nuclear Battlefields notes that at that time, California “ranks first in nuclear infrastructure with 80 locations and fourth in nuclear warheads… it has the largest number of military infrastructure of any state… every category of nuclear infrastructure is in the state.” And here’s what FEMA considered to be possible nuclear targets in the Bay Area by the late 1980s/early 1990s, as just a point of comparison:3

Now, Ing can write the nuclear scenario he wants to — it’s his book, and by not setting in “the present day,” he has a lot of latitude on these decisions. I just want to emphasize than in this narrow sense, he’s letting Harve off pretty easily with “only” four or five ground zeros in the Bay Area to contend with. The Soviet arsenal had nearly 7,000 ICBMs in the early 1980s, so it’s not like they had to be stingy about targeting.

At the same time, though, Ing makes other assumptions that make it much harder for Harve-and-co. than it otherwise ought to be. He doesn’t lay it out explicitly, but the chart of radiation dose rate he has at the front of the book implies, if you break it down technically, that he is assuming the Soviets were using weapons on the order of 10 megaton yield, as surface bursts, on basically every target that matters.4

The consequence of this is that the Rackam family are stuck with astoundingly high levels of radiation for the 36 hours that the book covers. Just nearly-unsurvivably high rates of radiation, even with all of Harve’s preparations. How high? The outside radiation dose rate at time of arrival for the first detonation is over 400 R/hr, and it jumps to around 600 R/hr with the arrival of the second wave of fallout. That means that over the course of 36 hours or so, the outside dose rate is well over 100 R/hr. To put that into perspective, a 100 R dose is considered the threshold for radiation sickness, whereas 400-600 R or so is likely to be fatal. So that means that the Rackam family are picking up significant dosages whenever they (occasionally) have to run outside, or spend any time in anything other than a very well-prepared, well-insulated space.

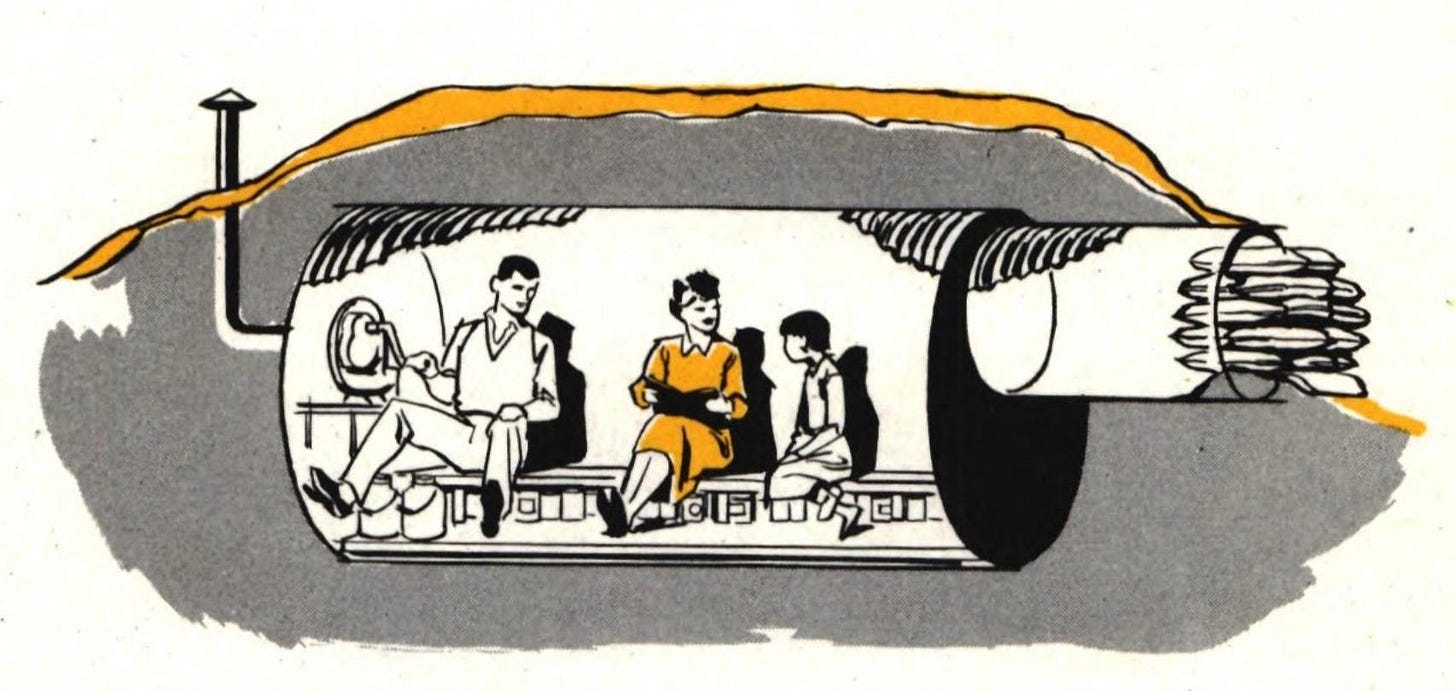

And Harve has in fact done quite a lot of preparation: he has modified his house over the years so that he has not just a basement, but a “tunnel” that provides very good protection against fallout, and he has better-than-most access to food and water. But even it makes for a near-miss in terms of survival, because the ventilation is poor, and so they spend half the book trying to make sure they don’t asphyxiate and also don’t pump in fallout while trying to get air.5

Why does this matter? It is part of the core contradiction of the book. It is a “survival” narrative at its heart, in which the protagonist is put up against horrible odds, and yet comes out on top. “Survival” books require the odds to be horrible, because otherwise, there’s no narrative payoff.

But it is also meant to be a “Survivalist” narrative, in the sense that it is a libertarian fantasy about how the well-prepared person can survive even the collapse of society, and is explicitly about how if you prepare adequately, you too can survive nuclear war. And therein is the problem: if nuclear survival is almost impossible for Harve, a fictional character with many qualities (and flying cars) that most of us don’t have, then how can this possibly make someone who is not a fictional character think that they have any chance of survival?

You might be wondering why I keep saying this is a “Survivalist” book, one that is explicitly posed to make you think that nuclear war is survivable. This is not some interpretation based on subtext on my part. It’s literally just the text. Of the book’s 260 pages, literally half of them are dedicated to non-fiction “how to survive nuclear war” articles, mostly ones that Ing wrote for other “Survivalist” publications and published in the years before Pulling Through came out. So it’s half novel, half “Survivalist” how-guide. Or as the back cover puts it:

Dean Ing has thought a lot about survival, and he wants as many as you as possible to pull through the inevitable disaster of nuclear war. That’s why he’s written this more-than-a-novel. Dean Ing lays all the cards on the table in this one. The story tells why. The articles and blue-prints tell how. PULLING THROUGH won’t save your hide all by itself, but it sure will give you a head start on pulling through by yourself.

Put aside whether nuclear war is “inevitable” or not, it’s not clear to me whether the book can really purport to do anything like this. Most of the articles in teh back are about things like, “how to rig up a hand-made ventilation pump to bring in air but not fallout,” which, frankly, is not something that almost anyone is likely to even try to do, much less be able to do. I’m not even sure it would really work — it’s not like Ing tested it with actual fallout!

Another, more mundane article is about how to rig up a bicycle so that it will power a small electric light, so you don’t have to sit in total darkness in your tunnel shelter. Someone could do that, I suppose, but… why, exactly? Is that really the best use of your time in that scenario? Or physical energy? This project in particular just feels like something meant to distract you from thinking about how probably everyone and everything you know and loved might be dead or dying horribly.

The discussion of how to rig up a simple chemical toilet is, by comparison, much more practical — and I admit that I always appreciate discussions of post-apocalyptic toilets, because they really serve to “ground” the basic problems of shelter survival in ways that more “clever” apparatus does not. This is your toilet for the next few days or even weeks. This is survival.

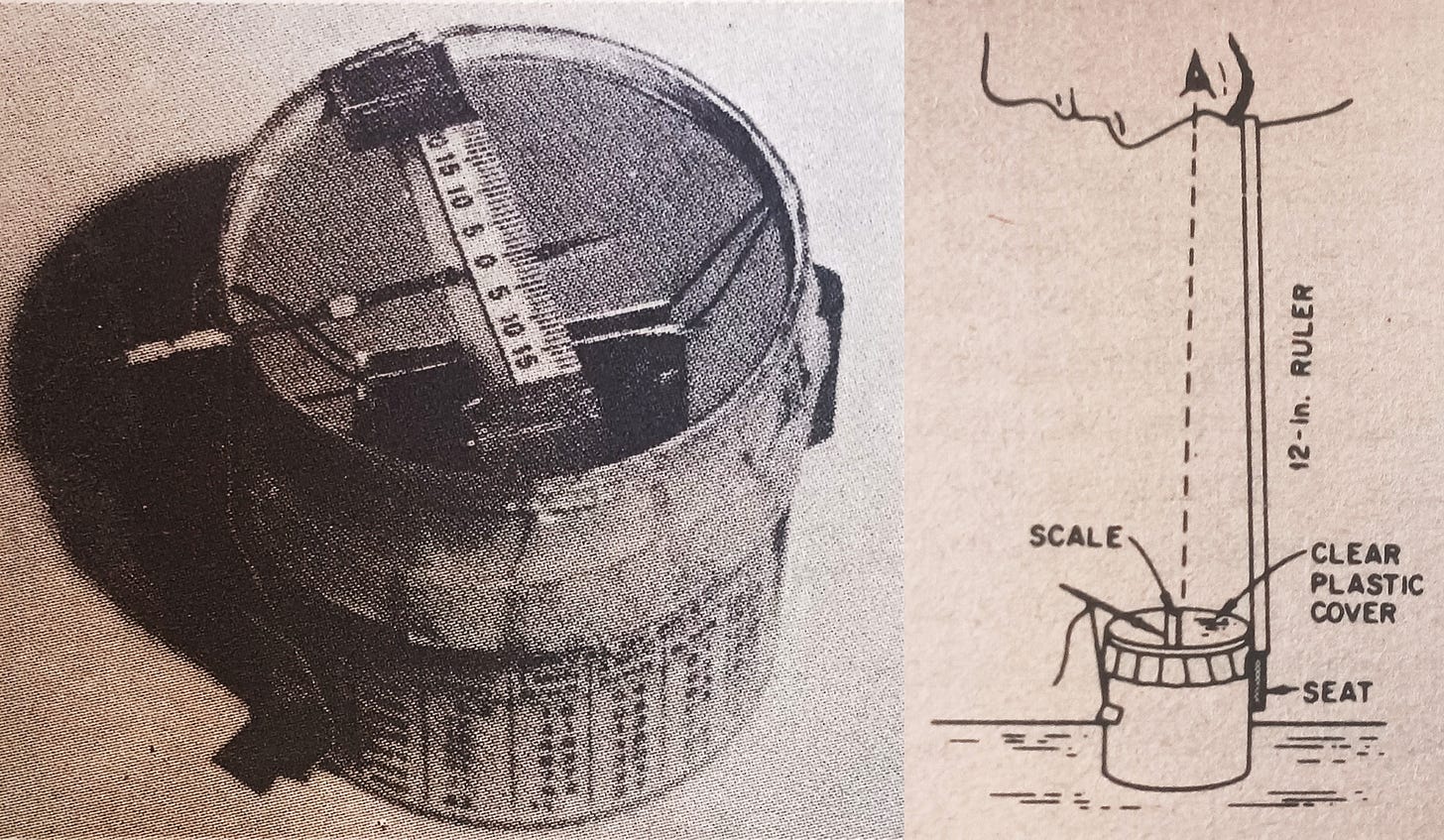

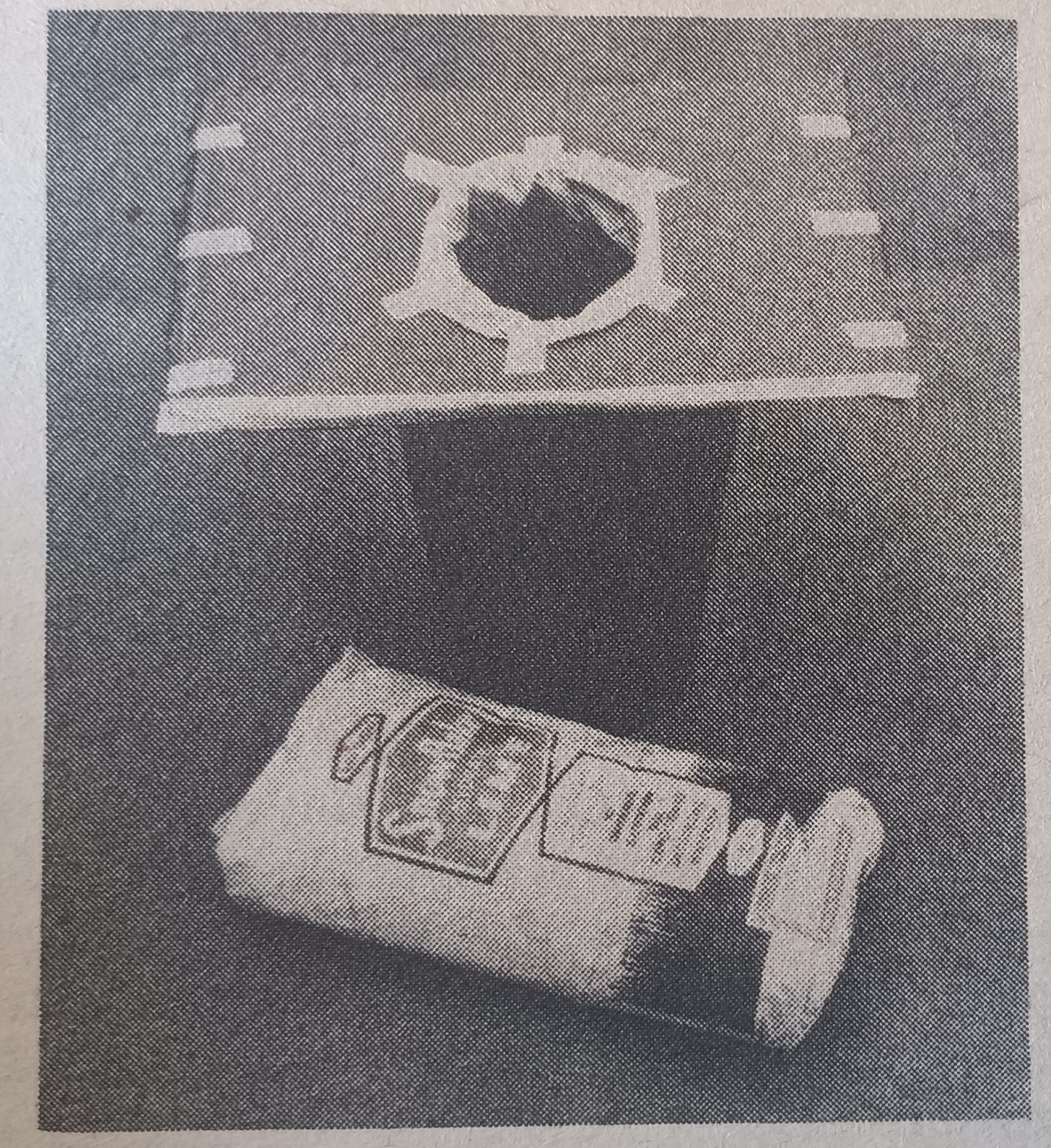

The last sixty pages of the book — one quarter of its total length — is a reprint of an article published by Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the late 1970s describing how to build a Kearny fallout meter, a home-made radiation detection device using household objects. The Kearny fallout meter, or KFM, is one of those ideas that is too clever for its own good. You can see why Cresson Kearny, an engineer, soldier, and think-tank guy, would be excited by it, and why people who were enthusiastic about Civil Defense would embrace it. “Anyone” could make and use one of these things, so the total cost for a population armed with radiation-detecting hardware is just the cost of distributing the instructions, right? Created at a time in which Civil Defense enthusiasm, and government funding, was low, this would solve a tricky problem, which was: even if people have fallout shelters, how do they know when to come out?

The problem with the KFM is that making a home-made radiation detector sounds pretty difficult for your average person. Even in Pulling Through, Ing has Harve’s engineer brother-in-law assemble it, and it takes time, and requires having the right materials on hand, and it requires some knack for following instructions and translating them into a physical reality. I think anyone who has tried to install IKEA furniture, especially with someone else, knows that none of this can exactly be taken for granted, and that’s for a bookcase or a cabinet, not a relatively sensitive scientific instrument on whose accuracy you are betting your life.

Reading the KFM is not easy, either. One must position one’s head at exactly the right distance, and note how much distance two pieces of aluminum foil change over time (measured by a ruler), and then plug that distance into a graph or equation that corresponds with a radiation measurement. Even in Pulling Through, the KFM is a pain to read, gives them inaccurate results at times and needs to be adjusted (or ignored), and takes up an inordinate amount of the time of the characters as they try to survive.

Again, I think that if the message of the book is, “you’ll die unless you can put together a radiation detector with household objects, get it working, and understand its output correctly,” then, well, I think most people are going to die.6

Which returns us to the “flying car” problem. As mentioned, Harve has a flying car:

My Lotus Cellular wasn’t tiny, but it weighed next to nothing; just the thing to drive when some bail jumper tried to sideswipe you, because the air-cushion fans could literally jump you over the big bad Buicks.

Ing was apparently obsessed with aerodynamics, and apparently in the 1960s built his own (non-flyinig) race car (the “Mayan Magnum”), so this seems like a very Ing-thing. The image on the cover looks to me like it is modeled off of the late 1970s editions of the Lotus Espirit, which, to my knowledge, could not fly, and did not have “air-cushion fans.”

It’s a cool idea, I guess? A car that has fans under it that can be used to allow it to jump? I believe I can imagine some of the reasons this doesn’t actually exist in reality, practical and social. And if it was just a strange thing in this “near-futurish” world, I would say, fine.

Harve having a cheetah, for example, is just a “strange thing.” Spot being a cheetah — and not, say, a dog — changes the plot very little, except to give Ing the opportunity to talk about how fast cheetahs are, how you might think twice before confronting a cheetah, and the fact that the cheetah prefers to defecate on raised surfaces. Spot really does very little in the entire story other than make newcomers uncomfortable, create an opportunity for the protagonist to have ample supplies of frozen horse meat, and occasionally allow the protagonist to make clear that he’d sacrifice Spot in a heartbeat if it was required for the survival of the group. OK, fine, sure, whatever.

But the fact that Harve’s car can “fly” is actually really important to the plot! Several times in the story, Harve’s survival relies on having a flying car, because he can hop over barriers, avoid car accidents, and twice he uses it to fly over water where bridges were off limits. It’s an important gimmick — the story would basically break, as written, without it.

And so, again, we have to ask: what is the point of this story? If the point of the story is, “you could survive nuclear war, just like Harve”… if Harve needs a flying car to survive, then we’re all dead, because nobody has flying cars.

The full plot of Pulling Through is about what you’d guess it to be. Harve picks up Kate as part of his bounty hunter job. While driving her to jail, they learn nuclear war is breaking out. They go to Harve’s place. His sister and her family meet them there. They try to reinforce his house before the nukes hit and the fallout arrives. They get in the shelter, they have one mishap after another (but they are clever and intrepid and educated and “pull through”). They have variously negative encounters with other people who, of course, did not prepare — some just sad, some that require “action” (Harve kills a few disposable baddies).

They wrestle with a couple mild moral dilemmas, but seem no more troubled by them than they do the question of whether Harve’s sister is a stern enough mother or not. Everyone is just so damned cheery and happy to be “surviving.” It’s the Survivalist ethos fulfilled: they finally found their “place” in the world.

Eventually they leave the shelter, have a bit more action, and end up living at Kate’s house. Harve eventually realizes that Kate has had the hots for him for ages, and now they’re together, hooray, curtain falls, they “pulled through.”

It’s not all fun, games, and smug commentary. Lance (Shar’s undisciplined son) dies. Some other (unprepared) people they try to help die. Neither of these are treated as particularly traumatic events, and the end of the book makes Harve out to be happy, healthy, and well-liked.

All of which adds up to, well, a bad book. Again, the only person who gets a character arc in the book is Kate, and that’s because she goes from a check-kiting “bimbo” to becoming a hardened survivor who comes to understand that Survivalism is hot, actually. Harve’s only transformation is that he loses some of the weight that a decadent society made him gain, and now is apocalypse-hot. Even Harve’s sister and brother-in-law seem to only barely mourn their dead kid, because, really, he did sort of deserve it because he was so undisciplined, right?

A hero’s journey, in the Cambellian sense (which I am not endorsing as an ur-myth), is one in which the hero is transformed by their experiences, often in ways that are irreversible. Frodo can’t stay in the Shire anymore after he wins the war, because his experiences fundamentally transformed him in ways that alienate him from his Hobbit peers. He saved the world, but at a high personal cost.

But Harve Rackam, as in the classic Survivalist/Prepper fantasy, seems to prefer the post-apocalyptic world to the one that came before. Sure, 66% of the United States population was killed, but he’s got a hot wife now, you know? Life is good, baby:

The chance of bone tumors, leukemia, and other long-term damage has leaped by an order of magnitude, which. means we have a small chance of dying that way within the next twenty years. Compared to life expectancy when this republic was young, those odds look bearable.

All of this is why this is thoroughly a “Survivalist” book and not really a “survival” book. It’s unvarnished fantasy. It’s moralizing and politicizing in the worst ways. It is about how a decadent society, especially an urban society, leads to fat, unprepared people. And how only the cleansing fire of total destruction will allow a new society to emerge. And what kind of society, you might ask? Oh, don’t worry, Ing tells us:

I suspect we’re through building beehive cities, those great complex organisms that proved so dreadfully vulnerable. … The federal gummint doesn’t interfere much with a state’s regional decisions now, and since the rural population pulled through in such good shape, the political climate is just what you’d guess: conservative.

It’s not the only place where Ing’s libertarian-conservative politics come through (at one point, Harve rants about how middle class kids today have it so easy, and that’s why they’re so into drugs, etc.), but it’s Survivalist lit, so one takes that as par for the course. It also isn’t the only time that Harve expresses disdain (or, at best, “pity”) for the city dwellers who didn’t prepare for, you know, the Soviets dropping 10 megaton warheads on top of them.

Anyway, it’s an amazing book, and I don’t mean that in a good way. It’s a perfect distillation of the Survivalist fantasy in some ways, even as it undercuts its own message by trying to show how clever Harve (and by extension, Ing) is. If surviving nuclear war requires being infinitely clever, with some rather exotic resources — a flying car!!! — then, well, I guess we’re all cooked.

In all seriousness, I find myself asking: what would a better book have looked like, even within Ing’s ideological (Survivalist) framing? If the goal was to showcase the value of preparation, it would require many fewer “close calls,” and rely less on clever hacks come up with in the moment (like the ventilation pump), or fantastical machines (the flying car), and more on things that Harve had quite reasonable done ahead of time. “Good thing I thought to equip my shelter with good ventilation, a filter, and a blower, just like The Family Fallout Shelter explained how to do,” Harve says, highlighting the problem but showing how careful preparation avoided it.

This would remove a lot of narrative tension, to be sure, but it’s not like there wouldn’t be opportunities to introduce tension in other ways, such as through the emotional development of the people inside of the shelter, who are coping with what the point of survival is if the entire world is destroyed. But that would have been a very different kind of book.

Of course, if Ing had any guts, he’d have had Harve crash the car into a tree in the end, and get eaten by his own cheetah. He survived the nukes, but he couldn’t survive his own ridiculous plot devices. Now that would have been a surprising, but satisfying, ending!

My population assumption assumes that Ing was envisioning an America on par with the 1983 census, but that’s just an arbitrary assumption on my part. The book doesn’t take place in 1983. But it’s hard to imagine he was assuming the population was lower than it was in 1983, so that only increases the size of the death toll. If, for example, one imagines that the original population was 347 million (2025 estimate), then that means that with 80 million survivors, the mortality rate was 77%.

Fun fact: “HARVE RACKAM” also works as an anagram for “Have Ark? Charm!”

This detail comes from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Risks and Hazards: A State by State Guide (FEMA-196, September 1990). This is not some authoritative listing of actual targets — but it gives some sense of what FEMA considered worth highlight for planning purposes about the kinds of facilities, locations, industries, military sites, etc., were possibly strategic targets by the Soviet Union. At some point I will write more about these kinds of “nuclear target/risk” maps and how they developed over time, as this FEMA map was just one in a sequence of such “target” maps.

I will spare you the calculations, which is code for, “I started to write it all up, and realized it was longer than the rest of the blog post, and that while there was a small and select audience who might be interested in that, it probably wasn’t worth it.” The short version of it is that a graph in the beginning of the book allows one to easily determine the H+1 dose of the fallout plumes and their time of arrival to Harve’s house, and that, combined with the map data giving some sense of the distances involved, allows one to make reasonable guesses about what size of a nuclear explosion would be necessary to produce those values. My best guess is that it is on the order of a 10 megaton detonation in each case.

Ing indicates that he thinks that Harve’s tunnel provided a protection factor of 200, which is a goodly amount (so any “outside” dose rate would be reduced by a factor of 1/200th), but his basement itself only provides a protection factor of 40 (not enough with those dose rates), and the rest of his house only provides a protection factor of 10 at most (definitely not enough). Strangely, Ing thinks that Harve putting on a rain coat raises his default protection factor from 1 (no protection) to 2 (a 50% reduction), which I think is ridiculously optimistic. Even MOPP suits don’t provide protection from gammas.

What’s strange to me is that you’d think that making a cheap, passive quartz fiber dosimeters, and distributing them widely, would be much easier than expecting a tens of millions of everyday people to build their own radiation detectors, and not that expensive compared to a lot of Civil Defense projects. Because that’s really all a KFM is, at heart: it shows you how much ionizing radiation it has absorbed in some small unit of time. I guess the difficulty is that for that kind of dosimeter, you do need a battery to reset it, and maybe that’s the difficult part. (Although I think the odds that people have batteries lying around their homes are much higher than them happening to have all of the ingredients for a KFM.) But I’m no engineer.

Well, I can understand nuking Stockton, but take offense at blowing up Santa Cruz. Did Ing hate hippies? Or was the target

the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey?

"But Harve Rackam, as in the classic Survivalist/Prepper fantasy, seems to prefer the post-apocalyptic world to the one that came before. Sure, 66% of the United States population was killed, but he’s got a hot wife now, you know?"

I've said it before and I'll say it again: just about every "survival" story, be it nuclear apocalypse or zombie, is one where the author and audience indulge in the fantasy "What if all the people who annoy me just ...died?"