Nuclear families

The imagery of the "family" in fallout shelter pamphlets, 1959-1961

The US government began promoting home fallout shelters in the late 1950s, as part of their overall Civil Defense program. The target audience for home fallout shelters was the 90 million-or-so Americans who lived potentially downwind of the direct targets of a hypothetical, full-scale thermonuclear attack by the Soviet Union. Which was a lot of people. It was too many people, and over too large an area — the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations both agreed — to warrant the building of mass, centralized shelters. But if every homeowner in the suburbs build their own shelters, well, that might save (the experts calculated) tens of millions of possible lives, and allow for a smoother rebuilding after the war ended.

The length of time one might need to stay in the shelter would depend on how intense the fallout was, which could range from not at all (and thus the shelter could be left immediately after that became clear) to intense-enough to require staying inside for two weeks or so.

So how do you get people to spend their money, and their time, building additions to their homes to prepare for nuclear war? For this plan to work, tens of millions of people would already need these shelters in place whenever the war started, and the shelters would need to be build with some care (and kept stocked with emergency supplies, and tools like flashlights, radios, and, ideally, passive dosimeters that would give the people inside an indication of their radiation exposure).

Among the answers pursued to this question was, in classic governmental fashion, to produce pamphlets and reports. These made the argument for the shelters themselves, explained the science and reasoning behind them, and, in some of them, gave suggestions as to how to build them.

As I mentioned when I wrote about Civil Defense last week, I’m fascinated with the imagery in these pamphlets, especially in the way they imagine what life would look like in a shelter during a nuclear war. I’m particularly interested in how they depict the people making or using the shelter, both in who is in the shelter — you’ll be shocked to learn it’s the most generic white, Middle American suburban family possible — and how they are using the shelter. So in this post I’m just going to be looking at the visual imagery of the family in just a handful of the many, many fallout shelter pamphlets and reports from this period.1

The Family Fallout Shelter, 1959

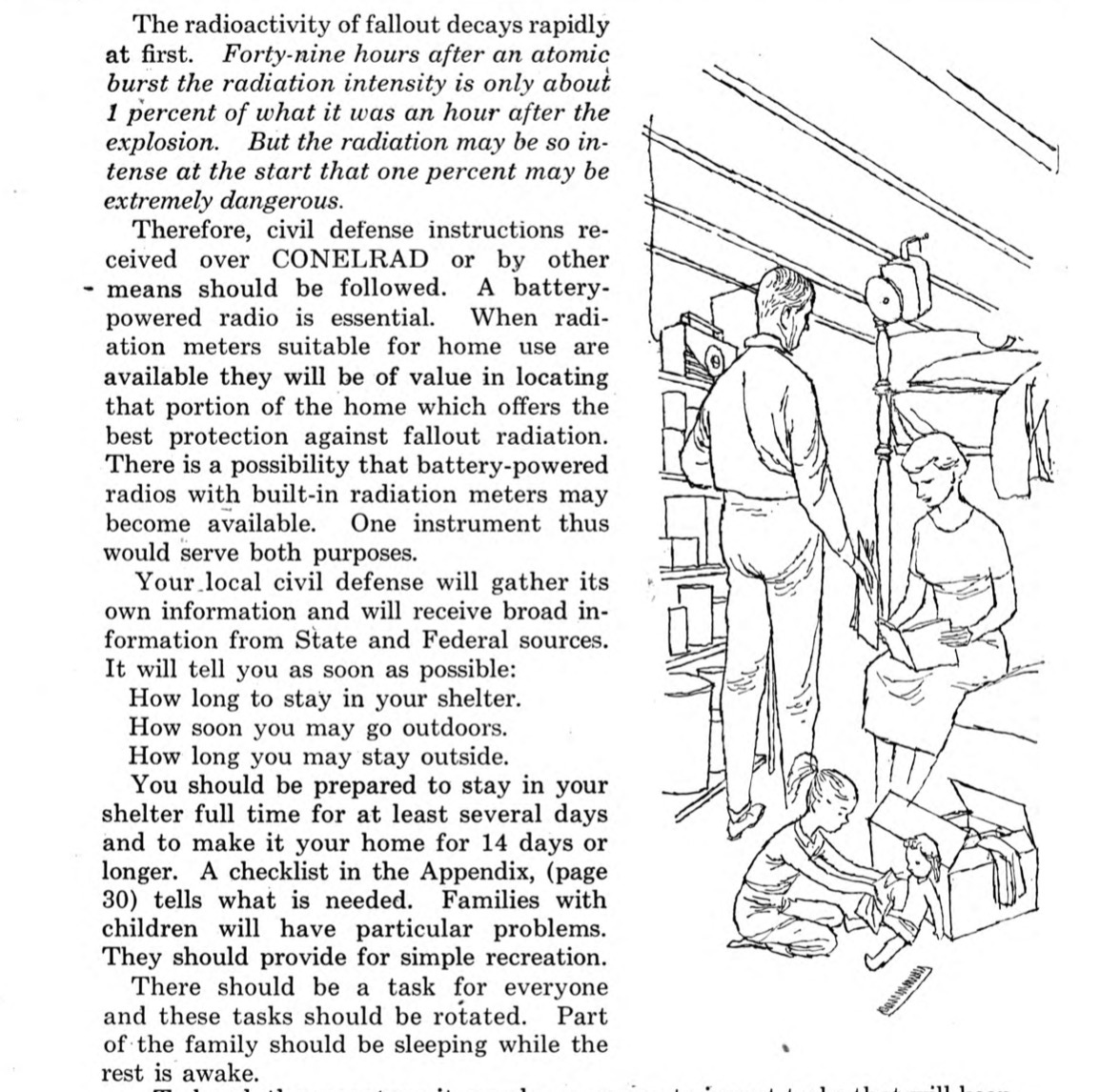

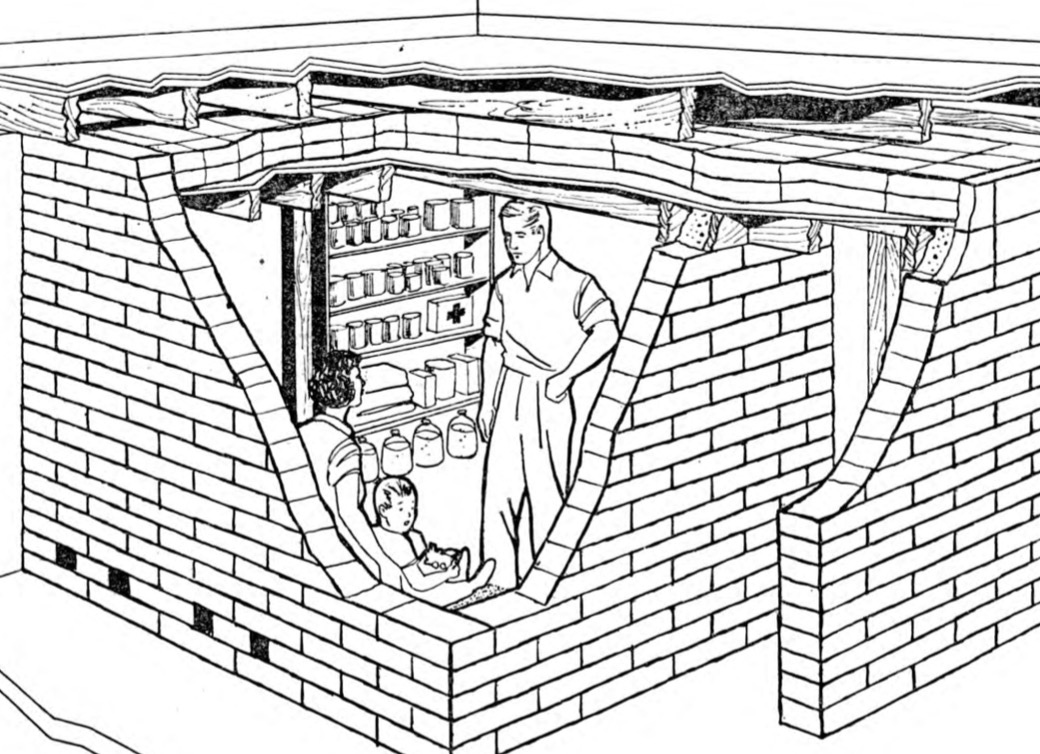

The Family Fallout Shelter was a pamphlet published by the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization in June 1959, and meant for widespread usage by the general public.2 It was 32 pages long, entirely in black and white, and surveyed a number of different shelter types (and even included architectural diagrams in the back). Its internal art varies in style and quality enough that I suspect it must have had multiple artists involved, and perhaps was cannibalizing a previous pamphlet for parts of it. Most of its illustrations are of solitary young-to-middle-aged white men with tight haircuts building the shelter itself. But there are several drawings showing the “occupied” shelters, such as this basement shelter.

And this aboveground shelter:

And this standalone, underground shelter:

These are very odd, fascinating images, if taken as scenes from a nuclear war. It’s easy to gloss over them, but look at them closely, as if they were full of meaning and portent, and they’re quite interesting.

Why does the “mother” always sit, and with her back to the viewer? While the “child” is always positioned so we can see their face. In the first one, the child is staring at… the wall? In the second one, they are looking at the “mother.” In the last one, the “daughter” lies in bed (sleeping? injured? sick?), while what I presume is meant an older “son” is standing in the under-furnished shelter.

The “father” of the first one is projecting the stoic confidence we expect our leading man to have in this kind of drama. In the second, he is only potentially hinted at — a lone arm at the far left. (Presumably the opened doors are merely illustrative of their function, but there is a certain fun mystery to imagining that they were intentionally left open.) In the last image, I am imagining that the seated figure is the “father” — why is his back to the “mother”?

These are all such odd arrangements. If I were a screenwriter or playwright, I would want to imagine the conversations that these drawings are illustrating.

Later in the pamphlet are other images of the family, in a somewhat different style. These ones are very vertical so I have included the text accompanying them.

Now, under what appears to be a different artist, the “mother” is now facing the viewer, and it is the “father” whose back is towards us. The child is engaging in “simple recreation” — playing with a doll. This time, rather than just sitting idly, the “parents” having reading materials. Are they reading survival pamphlets? Magazines? What does one read to pass the time — hours, days, weeks — in a fallout shelter?

The above drawing comes from a section on “housekeeping problems” in the shelter. It is just very interesting that this pamphlet, most of which is about constructing shelter, presumes to tell families how to organize their domestic affairs within it. But I do appreciate that they highlight the difficulties of sanitation and toilets, which is something that gets left out of a lot of fallout shelter imaginations. Where are people going to poop, if they are down here for two weeks? (Answer: If there is a toilet nearby, maybe in there. Otherwise, you’ve got to have barrels or something for people to go in. Perhaps the living will envy the dead.)

I also just want to highlight that family drawing above is only of one in a “shelter” because the text implies it; they could be anywhere, out of context. We appear to have a “father” laying out the “housekeeping rules.” We have two “daughters” this time, of varying age. And we have a “mother” who is wearing slacks! Which, while not totally taboo for the time, is still a bit progressive for a government pamphlet published in 1959.

There is one more image I want to highlight, which comes not from the pamphlet itself, but from advertising that was produced for the pamphlet:

I don’t know the story behind why these were created or how they were distributed. The measurements are apparently (based on online auction records of several) 28cm x 53cm (11 in x 21 in), so they weren’t that large. They were made out of cardboard of some sort. The art is actually signed (“Lee,” to the left o the pail), which is a rarity for this sort of thing.

What makes this stand out to me is how different it is from the pamphlet it describes. It is vivid and colorful, obviously. Its typography feels bold an intentional (if a little too jaunty for the subject-matter). It shows a woman who is not obviously coded as a “mother” (!), wearing much more fashionable (and skin-showing) clothing (!!), with a much more fashionable hair-cut (!!!), and she appears to be helping in the construction of the shelter (!!!!). These choices both make this such a more interesting image by itself, but these choices really just highlight how much the pamphlet itself is committed to a “passive mother” role for its adult women. Fascinating differences…!

Survival in a Nuclear Attack, 1960

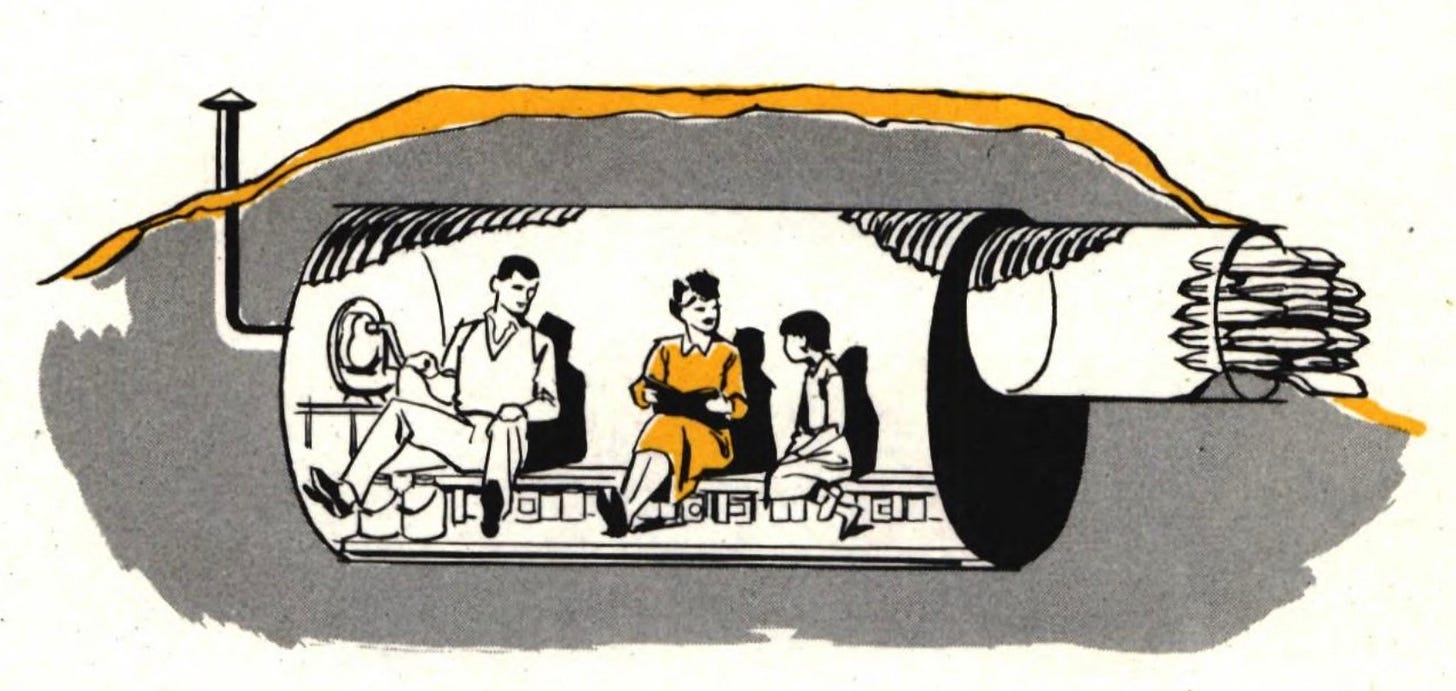

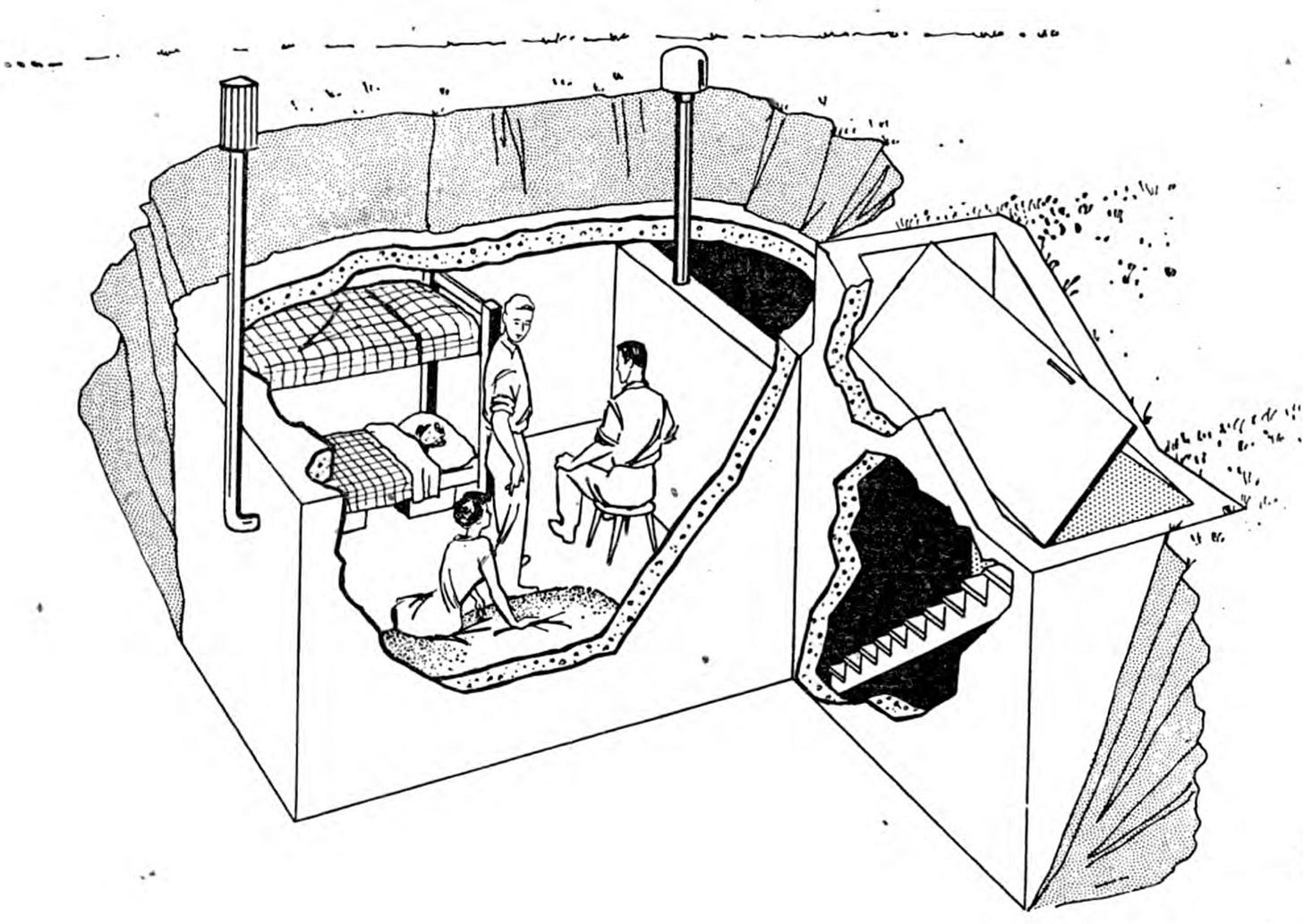

Survival in a Nuclear Attack was a report written by the New York State Committee on Fallout Protection, with its stated audience being Governor Nelson Rockefeller, dated February 1960. So it is coming out only a few months after The Family Fallout Shelter, and does re-use some of the imagery (such as the nuclear attack scenario). But most of its imagery seems original, and it has a distinctive and consistent graphic style that The Family Fallout Shelter did not have. And despite being a “report,” it is clear this was meant for mass distribution and consumption, and it had pretty high production standards and apparently plentiful copies were printed (you can pick them up for a song online; I have one).

The front matter makes clear that the Committee on Fallout Protection was assembled in July 1959, so right about the same time that The Family Fallout Shelter was published. The report is about twice as long as The Family Fallout Shelter, and is not strictly about how to build home shelters (it had an annexed “Report on Shelter Design” by an architectural firm that was designed for “architects, builders, and engineers”).

So it’s a very different “beast” than The Family Fallout Shelter. But I love its imagery so much that I couldn’t not include it.

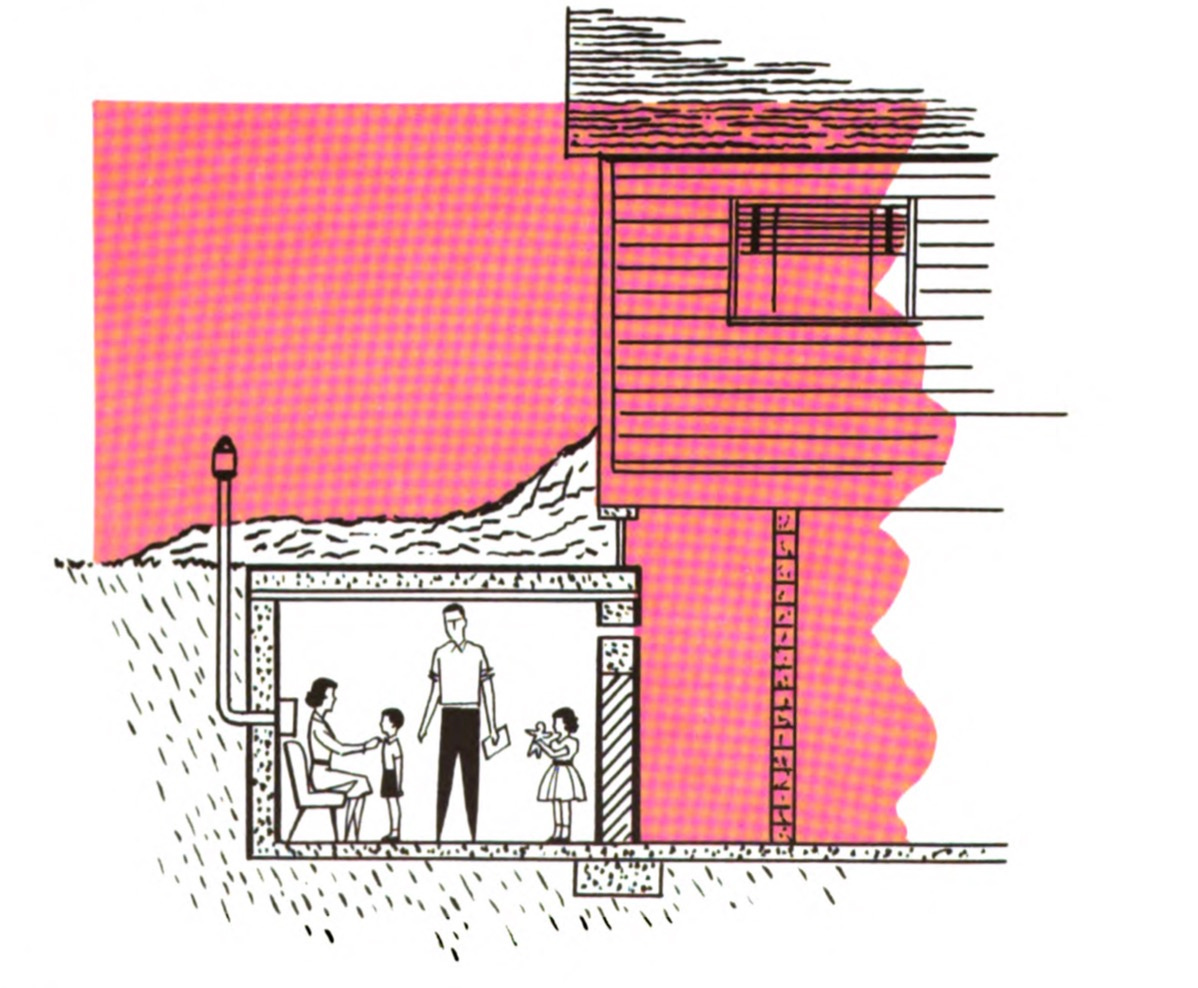

What a cramped little space for four people to spend hours — much less possibly weeks — surviving in. One chair. The “father’s” head grazing the ceiling, only about two feet from the settled fallout above. The two children — one obviously a “daughter,” the other presumably a “son.” But it’s more fun to imagine them as just two different “daughters.” “Father,” what are you doing, here? Why are you standing in the middle of room? What do you have in your hand? (Why don’t you have any feet?)

But if you thought that one was uncomfortable looking, the “compact shelter” is here to make it look spacious by comparison. Imagined being stuck in this cramped space, not being able to sit up straight, much less stand. They try to make it look bearable — the people in the photograph are almost comically absorbed in their reading material — but even spending a few hours in such a space, much less days on end, sounds like it would be a miserable affair even if you weren’t spending the entire time worrying about whether you were getting a fatal radiation dose, whether everyone you knew outside the shelter was dead, and wondering what would be coming next.

This is a more fleshed-out shelter for our nuclear family. Both “mother” and “father” are looking at the sleeping children, which is a better pose than any of those in The Family Fallout Shelter, but “father,” please sit down, you’re making me uncomfortable with your acing about. “Mother” is reading what appears to be a magazine, and seated in a way that reads as casual confidence to me. She’s not worried at all. The kids are, against all odds, sleeping calmly. She’s got a magazine, a dosimeter, lighting, a radio, a first aid-kit, food, water, clean air, and a place for “waste.” What’s there to worry about? They’ve got this. It’s going to be fine. I’m not saying we won’t get our hair mussed.

I will say that I think they really did good work with their color accent in this pamphlet. If you only get one color, run with it. It gives the whole thing a sense of polish and shine that The Family Fallout Shelter’s grim black-and-white just can’t compete with. Arguably, though, the stylized nature of the art bleeds through a bit too much into the “message” of it — it’s just a bit too slick, and a bit too calm, to feel believable.

Fallout Protection, 1961

One last pamphlet to look at is Fallout Protection: What To Know About and Do About Nuclear Attack, which was published in December 1961 by the Office of Civil Defense in the Department of Defense. Where Survival in a Nuclear Attack used red as its accent color, Fallout Protection uses what I think of as “Civil Defense yellow,” the yellow paint that became ubiquitous with fallout shelter signs and Civil Defense hardware (dosimeters, Geiger counters, etc.) in the Kennedy administration.

This pamphlet is more like the Survival in a Nuclear Attack report than it is The Family Fallout Shelter, in that it deals with a lot of generalities, but it does try to depict some actual different kinds of shelter designs, even if it doesn’t give explicit instructions on how to make them.

I pulled out the above image just because it shows the same kind of “compact shelter” as seen in Survival in a Nuclear Attack, but shows it being constructed, and — importantly — by the whole family! That’s right, even your wife can help make your basement shelter in the 1960s (as long as she’s wearing an apron, and not actually handling any of the tools… actually, is she just “supervising”? Is she wearing shoes?).

I also like this drawing of the “cheap” option, which is just a series of pipes covered in dirt. Still, it looks a lot more comfortable than some of the other “compact” shelters, when you draw them with a little depth. Here the “mother” gets a dress in “Civil Defense yellow,” which is appropriate clothing given the occasion. “Father” is engaged in the conversation (presumably about whatever “mother” is reading) while taking some time to bring some fresh air into the shelter. It’s still hard to imagine spending weeks in there, but it does a bit better at making this feel like a lived-in scene, even if it still a bit too clean.

How many shelters got built?

I’m not trying to be too critical of the art for all of these. It is serving a purpose, I get that. But there’s a disconnect, here, that it inevitably provokes. What would people actually look like inside a family fallout shelter, under the circumstances of nuclear war? What would their body language look like? What would their clothing look like? What would their children be doing? What would they be thinking and talking about?

I’m not saying these reports and pamphlets ought to have tried to capture something real. That would defeat their purpose, which was trying to sell people on the idea of building these shelters. A realistic depiction of how people might look in a shelter of this sort, under the conditions in which you’d be using one, would be… disturbing, to say the least. The tension and anxiety alone would be difficult to look at. It would not be people at their best. And, of course, showing that sort of thing would probably not encourage people to build these things. If you can’t imagine yourself having a good time inside a shelter — if you only can imagine them as tombs — then what are the odds you’re going to spend the thousands of dollars (in modern currency) to make one?

So what do these images tell us about the “family fallout shelter” in this period, in general? The target audience is clearly a very white, very middle-to-upper-class one, and the person making the shelter is presumably the “father” figure. If you are going to be charitable, you would say: well, that’s the target demographic, because high-density urban areas are probably dead in the immediate attack (and have a different sort of Civil Defense profile), and they are targeting people with disposal time and income who will be persuaded by the idea that through their hard-work and preparation, they’ll protect themselves and their loved-ones. So they would naturally take dead aim at the suburban dads in this period, if they even considered any alternatives at all.

In practice, it isn’t clear how many people did actually make them; perhaps around 200,000, all together, which is perhaps more than you might expect, but is very low given the population size they were hoped to protect, and the fact that, by 1961, 53% of Americans believed that nuclear war was a likely possibility. As Kenneth D. Rose put it in his book, One Nation Underground, “What is clear is that at the height of Cold War tensions Americans talked a great deal about fallout shelters, but relatively few Americans actually built fallout shelters.”3

These pamphlets weren’t the whole of the Civil Defense effort, to be sure, and this imagery wasn’t what made it succeed or fail. But I’ve had suspicions for a long time that part of the difficulty that Civil Defense faced in the United States is actually visible in such products: a limited imagination about who could be enlisted in the idea, and a vast, obvious, yawning disconnect between the official imagery of nuclear war — so clean and comfortable — and what most people imagined it would look like, if they tried to imagine it at all.

And for even more imagery, I might suggest (among other books)

The Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization was an Executive Office created in 1958 out of a merger of the Federal Civil Defense Administration and the Office of Defense Mobilization. In 1961, its Civil Defense functions were transferred to the Department of Defense, and it became the Office of Emergency Planning.

Kenneth D. Rose, One Nation Underground: The Fallout Shelter in American Culture (New York University Press, 2001), 201-202.

Hmm ... I was 5 at this time. My dad was working for Honeywell avionics and we were moving from contract location to contract location (Lockheed in LA, McDonnell/Douglas in St Louis, White Sands Proving Ground in Alamogordo, NM). In 1960 we moved to Germany as they were building the F-104 for NATO. I don't remember any mention of the nuclear threat but I do remember how upset people were when the Berlin wall construction was started (it was on TV a lot). By the time we got back to the US in '64, the duck'n'cover thing was waning. I do remember at least one drill in grade school in '64 or '65.

Some of the idea may have come from US servicemen that saw or experienced the backyard bomb shelters in London. Those actually were used and worked.

Very thoughtful post. I lived through this era, having been born in 1952. My family would have been in the demographic target, living in suburban Chicago with a nice big, back yard that could accommodate a shelter. I vividly remember seeing the ridiculous civil defense film Duck and Cover (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKqXu-5jw60), and engaging in drills where we hid under our desks when a warning siren sounded. I also recall reading about building a bomb shelter, perhaps in a newspaper or magazine. It was close to the time of the Cuban missile crisis, and my family was petrified--because my father had worked in X-10 at Oak Ridge as an electronics technician. During the cold war, he continued as an electronics engineer to work on missile components and underground nuclear testing. So I asked him, "Dad, why aren't we building a bomb shelter?" I was so disappointed when he said, "Honey, it wouldn't help." Another memory I have is that plans urged people to build zig-zag entrances to the shelters, since supposedly, radiation could not navigate around corners! I did not see that in the plans you found, however.