"Are you gonna drop the bomb or not?"

The West German nuclear zeitgeist as reflected in two pop songs

The threat of nuclear war in the early 1980s was acute in much of the West, with famously-large protests in the United States and Western Europe. Owing to their being on the “doorstep” of any future confrontation, with an extensive and dense deployment military and nuclear hardware deployed around their country, the West Germans were particularly concerned about the possibility of what even a relatively “limited” confrontation would mean for them. In their 1985 book Nuclear Battlefields: Global Links in the Arms Race, William Arkin and Richard Fieldhouse vividly explain what this meant in numerical terms:

“By virtually every yardstick you care to use,” a U.S. Army official told Congress in 1983, “Germany probably has the greatest imposed defense burden of any nation.” With 62 million people, it is equal in population to the United States west of the Mississippi. Yet it is no larger than the state of Oregon. Stationed on West German soil are more than 725,000 foreign soldiers (including their family members) and 495,000 West German military personnel. If the United States had the same proportion, it would have a standing military of about 3.4 million, or five times what it currently has stationed in the fifty states.

There are over 4,000 individual military facilities in West Germany (Oregon, by comparison, has thirty-four) and the U.S. military maintains well over 1,000 of these. In this densely populated and highly developed country, NATO military forces have free rights to maneuver on both public and private land. The United States conducts about 5,000 military exercises a year at 226 training areas. Eighty of these are considered "major" maneuvers.

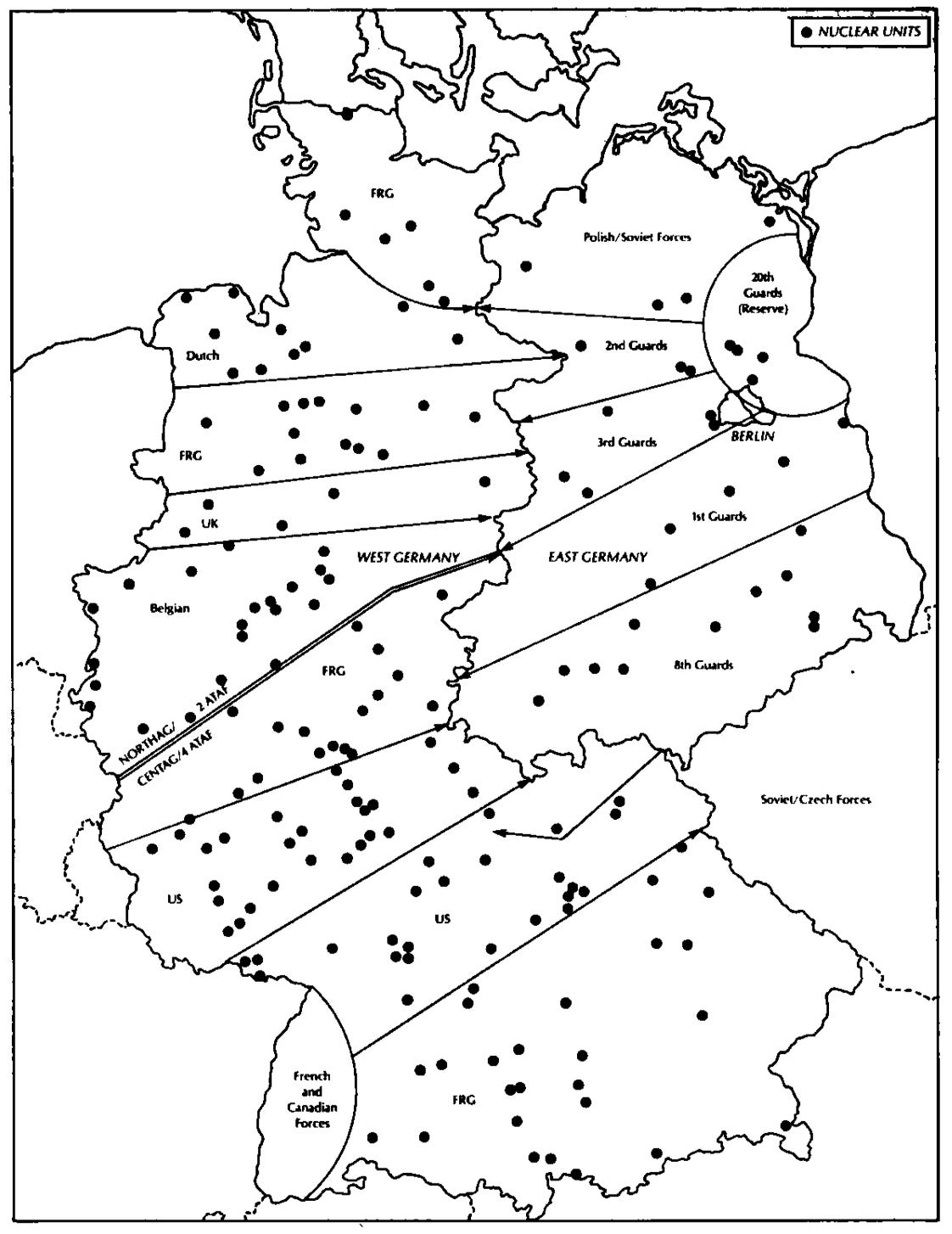

West Germany is the military center of Europe, the most heavily armed and densely nuclearized region in the world. The most discussed war scenario is for war in Europe. Over 2,700 NATO and 3,500 Soviet nuclear delivery vehicles and 9,000 warheads are deployed in Europe or facing Europe. Additional weapons in the Soviet Union and the United States are ready to “reinforce” the theater. In the surrounding seas, naval forces have still more warheads, bringing the region’s total to about 17,000 or one-third of the world’s arsenals. […]

The nuclear infrastructure in Europe is so extensive that even the most limited nuclear exchanges would involve hundreds of targets. As many as 1,000 of these potential targets are located in West Germany and East Germany alone.1

No surprise, then, that the German youth in particular took a rather dim view on what this would mean to their collective longevity. While the salience of nuclear warfare in the 1980s was high even in the United States, one has to imagine it was much higher in Germany.

Themes related to nuclear weapons in US-produced media in the early 1980s tended to be very “on the nose,” in the sense that there were many high-profile attempts to directly deal with nuclear weapons and nuclear war as “issues.” The Day After and WarGames were about as “direct” as you can get, with the latter only using then-hypothetical AIs and teenage hijinks as a way to “break” that “directness” a bit. Undoubtedly there were similar kinds of things produced in West Germany, but I find it interesting that the concerns about nuclear holocaust were great enough that the seem to “bleed” into other media in more subtle ways, including media that was then taken up in the United States without many Americans apparently realizing what it was about.

Two West German pop songs jump out to me when I think about this kind of phenomena. The first was a school “slow dance” staple in the United States, even when I was in school about a decade later: “Forever Young” by Alphaville (1984), whose members originated in the West Germany city of Münster.

Its nuclear themes are blink-and-you-miss them, and mixed in with some more gnomic verses (apparently the band’s English was not great), but the song’s meaning is fairly clear when you pay attention to what’s being said:2

Let's dance in style, let’s dance for a while

Heaven can wait, we’re only watching the skies

Hoping for the best but expecting the worst

Are you gonna drop the bomb or not?Let us die young or let us live forever

We don’t have the power but we never say never

Sitting in a sandpit, life is a short trip

The music’s for the sad menCan you imagine when this race is won

Turn our golden faces into the sun

Praising our leaders, we're getting in tune

The music’s played by the, the mad manForever young, I want to be forever young

Do you really want to live forever?

Forever, and ever

Forever young, I want to be forever young

Do you really want to live forever?

Forever young

It’s an excellent, if at times awkwardly-worded, summation of a certain generational fatalism: the sense, which many Gen X Americans I know have attested to me, that they did not expect the world to avoid a total collapse in their lifetime, and thus they were unlikely to live to an old age. It makes for an interesting juxtaposition, in a way: teenagers slow-dancing and slow-groping to a song about how they might be incinerated. “Are you gonna drop the bomb or not?,” indeed.3

A better-written song from the same period, which achieved even greater heights of popularity, is Nena’s “99 Luftballoons” (1983), with an English version released as “99 Red Balloons” (1984).

Despite its lyrics being relatively direct, and its music video featuring copious explosions, my experience is that when I bring it up today, most Americans don’t seem to actually know what the song is about. The beginning of the English lyrics lay out the plot:

You and I in a little toy shop

Buy a bag of balloons with the money we've got

Set them free at the break of dawn

'Til one by one, they were gone

Back at base, bugs in the software

Flash the message, "Something's out there!"

Floating in the summer sky

Ninety-nine red balloons go byNinety-nine red balloons

Floating in the summer sky

Panic bells, it's red alert!

There's something here from somewhere else!

The war machine springs to life

Opens up one eager eye

Focusing it on the sky

When ninety-nine red balloons go by

In other words, the protagonist in the song has released a large number of balloons, which the early-warning systems of the military installations so densely clustered in the band’s native West Berlin mistake for “something,” causing “the war machine” to “spring to life.” As the song continues, the militaries of the world scramble their forces (the “knight of the air,” with everyone believing themselves to be a masculine hero, a “Captain Kirk”), believing this to be “what we've waited for / This is it, boys, this is war.”

The German version is much the same as the English, but does change it slightly. Instead of “There's something here from somewhere else!”, the German has “Hielt man für Ufos aus dem All,” which translates to, “They thought they [the balloons] were UFOs from outer space.” A later verse explains that after the seeing the West blast the balloons out of the sky, their “neighbors” (the East Germans/Soviets) don’t understand and feel like they were under attack, leading to the full war.

Personally, I prefer the ambiguity of the English version. Making it about a fear of UFOs undercuts the narrative’s plausibility, and makes it more farcical. The English version allows for the interpretation that the balloons are interpreted as some kind of enemy attack, and makes the song a better warning about the dangers of a hair-trigger posture. The US and Soviet early warning systems did, famously, give false alarms, including by misinterpretation of benign objects: in 1960, a NORAD station in Greenland mistook the rising moon for dozens of incoming Soviet missiles, and in 1983 (unknown to Nena), a Soviet early-warning system interpreted the sun reflecting off of clouds in an unusual way as incoming ICBMs, to name two relatively-easy to corroborate cases.4

I’ve used “99 Red Balloons” when teaching about the Cold War nuclear threat and its popular salience — college students today, in my experience, tend to be only dimly aware of the song at all, and it definitely comes as a surprise for them to look at the lyrics closely. I’ve never used “Forever Young” in this context, because I hadn’t really given it a lot of attention myself until relatively recently, but I suspect the two paired up could produce interesting conversations about whether or not their own anxieties (which are numerous, although generally not related to nuclear war) “bleed out” into the art they produce and the media they consume.

William M. Arkin and Richard W. Fieldhouse, Nuclear Battlefields: Global Links in the Arms Race (Ballinger, 1985), 101-103.

Amusingly, a week ago I happened to be listening to the “1st Wave” station on SiriusXM radio, and the DJ did an entire theme on “disaster songs,” and included “Forever Young” as his top “I bet you didn’t know this was about nuclear war” offering. But reader, I did know!

It would be interesting to know if there were studies on how “youth” at different moments in the 20th century viewed the possibilities of “the future.” My sense, as a teacher (who is not a parent) is that it is somewhat uncontroversial among college students today to imagine some kind of major collapse in the next generation or two, but that this is not acute-enough that it derails their immediate preparation for a career. Daniel Ellsberg, in his The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner (2018), says that while he was an analyst at the RAND Corporation in the 1960s, he declined to have a portion of his salary invested into his pension because he did not think the world was likely to live long-enough for it to be cashed out, which is one of the only accounts I have ever heard of someone “putting their money where their mouth is” regarding such threats.

There are also accounts of birds (geese or swans) setting off false alarm sensors, but these are much harder to corroborate with serious sources, and may be apocryphal. There have been many other causes of nuclear false alarms other than misinterpreted environmental sensors, but that’s a larger topic than I want to get into right now, having spent too much time trying to run down good sources on the bird stories and finding that they are pretty hard to confirm!

I made several long trips to the FRG in the early 1980s, including through the collapse of the SPD/FDP coalition, the rise of the Greens, and the public protests over the stationing of the Pershing II and cruise missiles. 99 Luft Ballon was all over the radio at the time, but the band that seemed to capture the sense of the times was BAP, who made lots of references to the political and military situation in their songs. "Zehnter Juni" was a pretty explicit complaint about what was going on, as was of course one of their greatest hits, "Kristallnaach," albeit a more indirect statement. BAP never got much traction outside Germany, perhaps because they wrote, and sang, in the Cologne dialect, but they were HUGH in Germany.

By the by, one of my favorite stories of the time was about a tv ad put out by the Greens. It showed a truck driving down the street, dropping off aluminum foil missiles in front of each house. The Greens at the time were just getting started, so they didn't have the money for the sort of slick and sophisticated ads common from the mainstream parties, but man was that an effective ad. Also, lots of street-level anti-Americanism, and general ignorance in the population--I had more than one conversation where my German colleague did not know, and could not believe, that it was German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt who first asked for a NATO response to the upgrading of Soviet SS-20 IRBMs. He later claimed that he did not mean Pershing IIs.

The 2009 reboot of 99 Red Ballons has a wonderfully retro look to it with the 8 bit graphics and Putin standin:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHTMZX898mo

On the other hand there's no better example of the kind of soul searching that was taking place in the '80s in the face of nuclear annihilation than "Stand Or Fall" by The FIXX:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hAofFHPRZTE