Strange games

Even if you can "win" some nuclear video games, maybe it's still good advice "not to play"

The computer age and the nuclear age are conjoined twins. So it is unsurprising that nuclear weapons and nuclear war have been featured in video games from very early on.

My sense is that you could create a rough taxonomy of “nuclear war video games”:

Games that feature nuclear weapons as an overarching thematic element, or as a broad metaphor, such as Trinity (1986).

Post-apocalyptic games that take place after a nuclear war, such as the Fallout series (1997-).

Games that are general “war fighting” games that feature tactical nuclear weapons as part of their arsenal of weapons, such as Command and Conquer: Red Alert (1996) or Starcraft (1998).

Games that are specifically about planning and fighting a strategic nuclear war.

There is overlap in the above, of course (tactical nuclear weapons feature in the later Fallout games), and edge cases. In the Sid Meier’s Civilization series, nuclear weapons are part of the “arsenal” of possibilities, but are considerably more “strategic” in their importance and effects than nukes are in most games of that sort, for example.1

The last category, games specifically about nuclear war-fighting, are particularly interesting to me. They bring up interesting questions about how we depict and think about nuclear war, culturally, and how the limitations of “gameplay” contort serious topics. There are deep links between the kind of “war gaming” that was/is by strategists at places like the Rand Corporation, and the kind of “war gaming” that first flourished as physical games and later led to several genres of computer games, as Jon Peterson explains in fascinating depth in his (fractally-dorky) book Playing at the World, a history of role playing games that draws the fascinating (and mutually-reinforcing) connections between those people who regarded “war gaming” as a tool for thinking about how to wage war and those who regarded it as a way to play an intellectually challenging and fun game.2

People have sometimes used the word “game” when talking about NUKEMAP, which I always find strange. There’s no goal, no end-state, no players, no score… where’s the game? It’s a simulation of sorts, and yes, of course, simulations and games are wonderfully fuzzy and often overlapping categories, but while I would not necessarily want to die on the hill of any particular definition of “game” (anymore than “art”), it strikes me that it certainly isn’t obvious that there are “game” elements to it. One can, of course, invent “games” wherever one pleases, but that usually involves adding those elements that are otherwise lacking in “non-games.” If authorial intent matters, I proclaim: NUKEMAP is not a game.

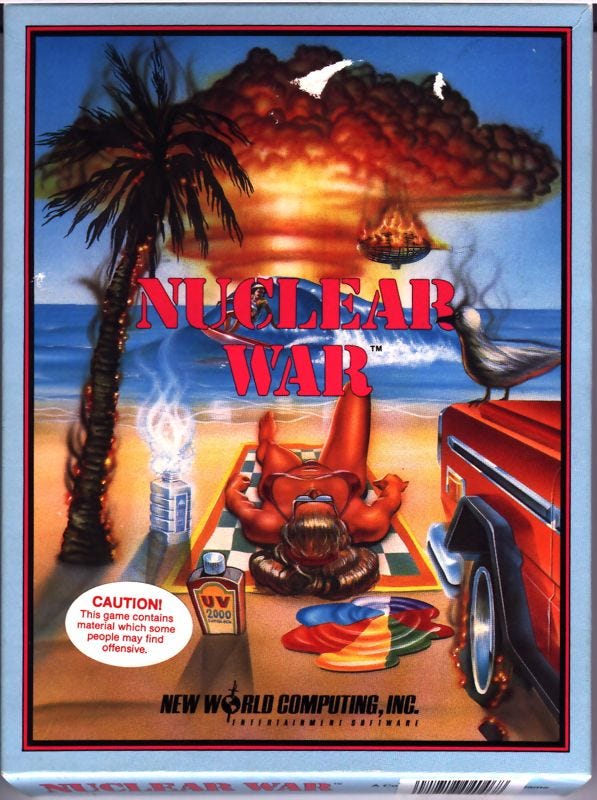

Nuclear War, a 1989 PC game from New World Publishing, definitely is a game. It has a distinctly late-Cold War aesthetic to it: mocking, sardonic, sarcastic, silly, satirical:

For your sake, dear reader, I played it… for about 5 minutes. I will not bore you with the details. The gameplay is not deep. You nuke and get nuked — mostly the latter. There are a few other gameplay elements, but they are pretty feeble. It is entirely forgettable. The cover is probably the most “interesting” aspect of it, read as a cultural artifact of 1989, and is what I would file under “Do Not Touch”:

A more recent game of the same “nuke or get nuked” style, and presumably much more one at that, is Introversion Software’s DEFCON (2006). Its stylized aesthetics are deliberately derived from the Big Board of the 1983 film WarGames:

The game can be played with multiple players over a network, or against AI opponents. The game starts with players deploying their assets: ICBMs/missile defenses, airfields (which can have defensive fighters or offensive bombers), radars (which reveal incoming attacks), submarines, and surface ships (carriers and destroyers). Each player controls a continent, more or less, which contains a number of cities. As time ticks on, the DEFCON level automatically lowers from 5 (no hostilities) to 1 (nuclear war). In the early phases, players can scout for enemy targets and even attack enemy planes and submarines without using nuclear weapons. Once DEFCON is set to 1, then things tend to go haywire.

The game’s “strategy” is tied up in the fact that each of the assets can be used in different modes, usually offensive or defensive in nature. So missile silos double as anti-missile defenses, but can only be in one mode at a time. Once a missile launches from a submarine or a silo, the launcher’s location is revealed, and can be targeted by offensive or defensive forces. The players can target their nuclear arsenals (from bombers or missiles) at the strategic forces of their opponents, or at their cities.

If nukes hit cities, the attack is announced in bold letters with a number killed. Large cities have enough population to take multiple hits. The megadeaths pile up. By default, players have a score that increases by 2 for every enemy kill, and goes down by 1 point for every unit of their own killed. So the winner is the one who kills the most and/or loses the least.

I played this game a bit when it first came out, almost 20 years ago. As a game, it is far more engaging than Nuclear War. There’s some real strategy to it in balancing those offensive/defensive impulses, and choosing which continent to start with, as their relative sizes (and locations of cities, which are always the same) are the main differences in their strategic situations (Europe, for example, is small and dense, and favors a “turtling,” defensive strategy; Africa, by contrast, is so large, and has its cities dispersed, and this makes it especially vulnerable and hard to defend).

To its credit, DEFCON is meant to be “fun,” but it doesn’t entirely make light of its subject matter, which is a big contrast with Nuclear War. Aside from its grim, dark aesthetic, the soundtrack consists of moody music and occasional sounds of human suffering (like a woman crying), obviously calculated to make for an unsettling experience. There are, you know, worse soundtrack choices they could have made.

So, a better game, if this kind of game is to your tastes. Is it a better simulation? I’m not sure. Apparently there have been long debates in the gaming community about the lack of “balance” in DEFCON, because of the aforementioned differences in geopolitical situations. Players are absolutely not on an equal footing; playing well as some countries is harder than playing others. In most online, competitive games, balance is considered to be of supreme importance, because it is how one measures the relative skill of players.

The accusation that DEFCON lacks balance is admittedly somewhat absurd if viewed from the perspective of its many “unreal” aspects: it is far, far more “balanced” than the real world is. Imagine some of the modifications that would be necessary to make DEFCON even slightly realistic when applied to the modern world:

Only 9 countries would have nukes. Nearly 90% of them would be in the possession of two countries.

Delivery vehicles (missiles, bombers, etc.) and capabilities would vary dramatically by country.

The offensive/defensive balance would be tilted strongly towards offensive, with missile defenses in particular being very limited and unreliable.

While there is some ability to “mod” DEFCON, on a first perusal I don’t see any that have tried to make in more realistic in this sense. It would be a fun experiment to try — but it would certainly not make for a fun game. As I wrote in a review of Civilization VI some time back:

There are clear issues of “balance” associated with technologies like real-life nuclear weapons: they are, to use the jargon of gamers, “overpowered.” Real nuclear weapons make for poor gameplay. And for the record, history itself was not that fun of a game for most players, either.

Of course, DEFCON is arguably “just” meant to be understood as a “game,” with no expectations or presumptions to realism. I can accept that, to a point. I’m not a culture scold, and I recognize the factors that are at work in making games “games” (and not simulations) and also making them economically and/or culturally “successful.” I also get that the people who enjoy playing DEFCON are not necessarily implying that they would delight in actual nuclear war, nor imagining that it is a realistic portrayal of anything in the real world.

But I do raise a bit of an eyebrow, as I do with popular depictions of nuclear war in any media, because such things do form (and reflect) how our culture understands these weapons and their implications. What DEFCON taps into, and reinforces, is the same control fantasy about nuclear war that has been a dangerous through line of military planning and political posturing since 1945. And I suspect that it is hard to “remember” how unbalanced the reality of the situation actually is, both in terms of nations and in terms of offense and defense, while playing such games.3

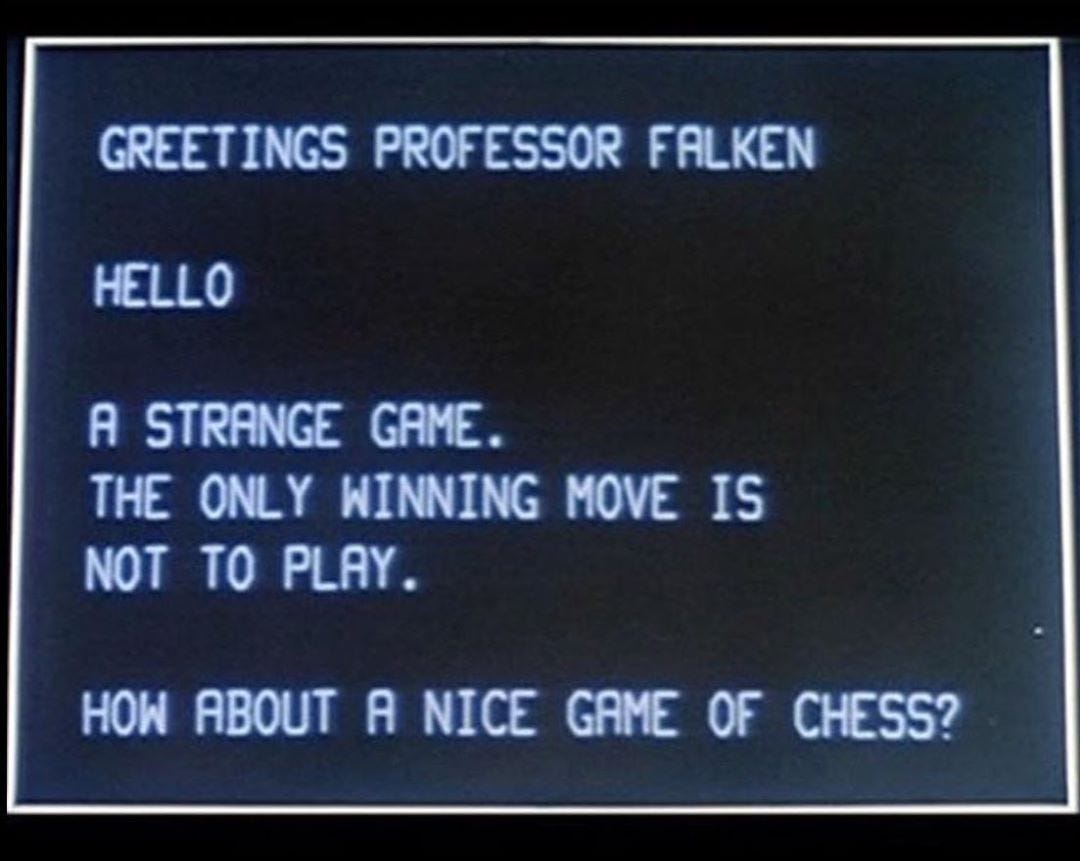

The film WarGames ends with a justly famous quote from its game-loving, AI antagonist about thermonuclear war:

A STRANGE GAME.

THE ONLY WINNING MOVE IS

NOT TO PLAY.

The question for me is, can any game about nuclear war that is built around a control fantasy actually cause the player to reach such a conclusion organically? I suspect the answer is no. This doesn’t mean that making a nuclear war game is itself impossibly fraught — yet another “better not to play” situation — but I do think that if one is trying to actually do something intellectually interesting in the arena of nuclear games, one has to take a different approach entirely.

I am going to refrain from talking about the famous “Gandhi as nuclear warmonger” bug/feature for the moment — it feels like a topic that would warrant a post of its own, as there are several interesting layers to it. But I am noting that I am very much aware of it!

I’ve only read the (out-of-print) first edition of Peterson’s book, which is excellent if you can get your hands on it and are of an extremely dorky turn of mind. (Consider this to be a strong disclaimer/qualification. Obviously I am in this category myself.) A new edition is in print again as two volumes from MIT Press, but my reading of the publicity materials makes me think that the parts relevant to the history of “war gaming” (and not specifically Dungeons & Dragons) are set to be in the as-yet-released second volume.

Am I right? Am I wrong? I don’t know. If I were able to dictate the research priorities of social scientists, I would assign to them research questions like: “Does playing 10 hours of DEFCON change people’s perceptions of nuclear war, missile defense, etc. in a measurable and durable way?” This strikes me as a very interesting, and possibly quite “answerable” and empirical question (within the standard caveats about method, replication crises, etc.). Otherwise it feels like we’re all just guessing in the dark. I blame my (excellent) social science colleagues, especially Kristyn Karl and Ashley Lytle, for influencing me to think in such a way, as it is not normally how historians approach such matters.

Update: a reader helpfully pointed out that a study on DEFCON’s impact on nuclear attitudes was in fact published: David Waddington, Tieja Thomas, Vivek Venkatesh, Ann-Louise Davidson, Kris Alexander, “Education from inside the bunker: Examining the effect of Defcon, a nuclear warfare simulation game, on nuclear attitudes and critical reflection,” Loading… 7, no. 12 (winter 2013), 19-58.

It appears to be a thoughtful paper. The framing section in particular is generally good, though the authors’ perceptions of what a “real” nuclear war would be seem quite off to me, if they think DEFCON is a proxy for that. It comes with the same limitations one has on university subject-pool papers (using 141 students, all from the same American university, as the test subjects — totally common, but fraught with obvious limitations), and I am sure I would have asked somewhat different questions, personally.

The basic takeaway (as I skim it) seems to be that playing DEFCON seems to have made the students more likely to believe that they would not survive a nuclear war, but that they were less likely to believe that nuclear war was probable in the next 10 years. The statistics is over my head, so I could be reading these wrongly. They also received some qualitative data from students on how they regarded DEFCON as a proxy for “reality,” and (hurray), at least some of the students expressed that they did not think it was very realistic. On the other hand, one of the students wondered why the soundtrack including sounds of human suffering, as opposed “jungle jumping music or something else.” Well. And of course most of the students seemed to be unimpressed by the aesthetic choices… I am betting that nearly zero of them have seen WarGames.

Interestingly, any effect of playing DEFCON appeared to be somewhat more pronounced on female players than male ones. This doesn’t entirely surprise me, and I could conjecture cultural reasons for that.

So how does this answer my original question? I’m not sure. It does reinforce the idea that the game may have an impact, but the nature of that impact is still a little unclear to me, other than the fact that a statistically significant number of students did appear to map DEFCON’s depiction of nuclear war onto a “real” depiction of nuclear war. Which, considering how much DEFCON (deliberately) diverges from reality, is not necessarily a good thing, even if one believes that the impressions the students took away (nuclear war is bad) are in some ways the “right” ones. The fact that the “nuclear war would be really bad” seems to have become possibly linked to “and that’s why it won’t happen” is indeed one of the concerns I have with a lot of anti-nuclear war messaging which (in my mind) often relies on very unrealistic “scenarios.”

To put it another way, did the students who played DEFCON in this study conclude that “the only winning move was not to play”? Some seem to — although those same ones also seem to have concluded, “and thus nobody will play,” which is not quite the same thing at all!

Are you familiar with <<Bravo Romeo Delta>>? It too seemed like a mix between your NUKEMAP and DEFCON mixed in with breakdowns in command and control as the conflict goes on but made for the Amiga back in the day. It's available by Abandonware.

Kudos for the Trinity reference, though missed Balance of Power - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balance_of_Power_(video_game)