"Take me to your shelter, leader!"

Do you have what it takes to be a shelter manager after World War III breaks out? Take this quiz from 1973 and find out!

When people think of fallout shelters, they tend to think exclusive of the “family fallout shelter,” the sort that Americans were encouraged to build in the early 1960s.

But this period was also when public, communal shelter spaces were being identified and labeled with those iconic three-yellow-triangles-in-a-circle “FALLOUT SHELTER” signs that one can still find on the sides of large buildings in many urban areas.

Most such areas marked as such were not built to be shelters, but were identified as shelter spaces as part of a US government effort in the 1960s. They were meant to be stocked with supplies, including canned food, water, and even “sanitary facilities” (chemical toilets), that would allow some number of the local population (indicated by the “capacity” label on the sign) to ride out a few days, or even weeks, of radioactivity after a nuclear war.1

So think of this kind of “shelter experience” as less of a “you and your family huddled into one small room” experience, and more of a “you and 30-500 other people are crammed into a large room” sort of situation. And those “other people” are going to be men, women, and children of all ages, all walks of life, and possibly all strangers.

During the 1960s, many “shelter experiments,” involving thousands of volunteers, were conducted in the United States, with the goal of understanding how well your average American would handle such conditions. They generally reported that people were pretty good about it, but it’s a little hard to feel like those results are that reliable given the plain fact that they could not truly replicate the state of mind of a full-scale nuclear war for any of the participants. And people could “defect” — leave the experiment — without it being suicidal, which undoubtedly served as a “release valve” for the most unhappy members.

The official guidelines for these shelters recommended that they be run as pretty tight ships. Rationing of food, attending to the sick, resolving differences, keeping people’s minds and bodies active — these all require some degree of coordination. As do other necessary activities like tracking radiation levels, removing trash, and keeping the chemical toilets hygienic.

And so it was recommended that every shelter of this sort have a designated shelter leader. The Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DCPA, part of the US Department of Defense) had this to say on the value of good leadership in their Attack Environment Manual of 1973:2

The description in this Chapter of the probable shelter environment and ways of coping with it should leave no doubt about the value of trained leadership —shelter managers, as they are called. Of course, leaders will emerge in response to pressing needs, and groups can muddle through very difficult situations. There will be many situations, however, in which trained leadership will make the difference between life and death for substantial numbers of citizens.

I find this entirely plausible. So who would make a good shelter manager? The text continues:

Who should be recruited as shelter managers? It appears virtually impossible to take someone without management experience and turn him into a manager through exposure to a short course of training. It is, however, quite feasible to take someone with a strong management background and in a short time give him the technical information required to manage a shelter effectively. This suggests that upper-level executives from organizations housed in structures designated as shelter facilities are potential candidates.

The ideal manager appears to be one who is capable of working in ill-defined situations; one who can provide structure and direction and then proceed with the tasks at hand; a person who is creative in the face of unique, unprecedented problems; a person used to the tumult of situations demanding decisions; an effective communicator who has practice in dealing with people.

Which is an interesting approach. I am less sure I find this to be as plausible, as it seems a little all-too-convenient that the ideal leaders of a shelter happen to be the “upper-level executives" of wherever the shelter happens to be located. Perhaps it’s our current zeitgeist, but I’m not super enthusiastic about most CEOs being put in charge of collective welfare.

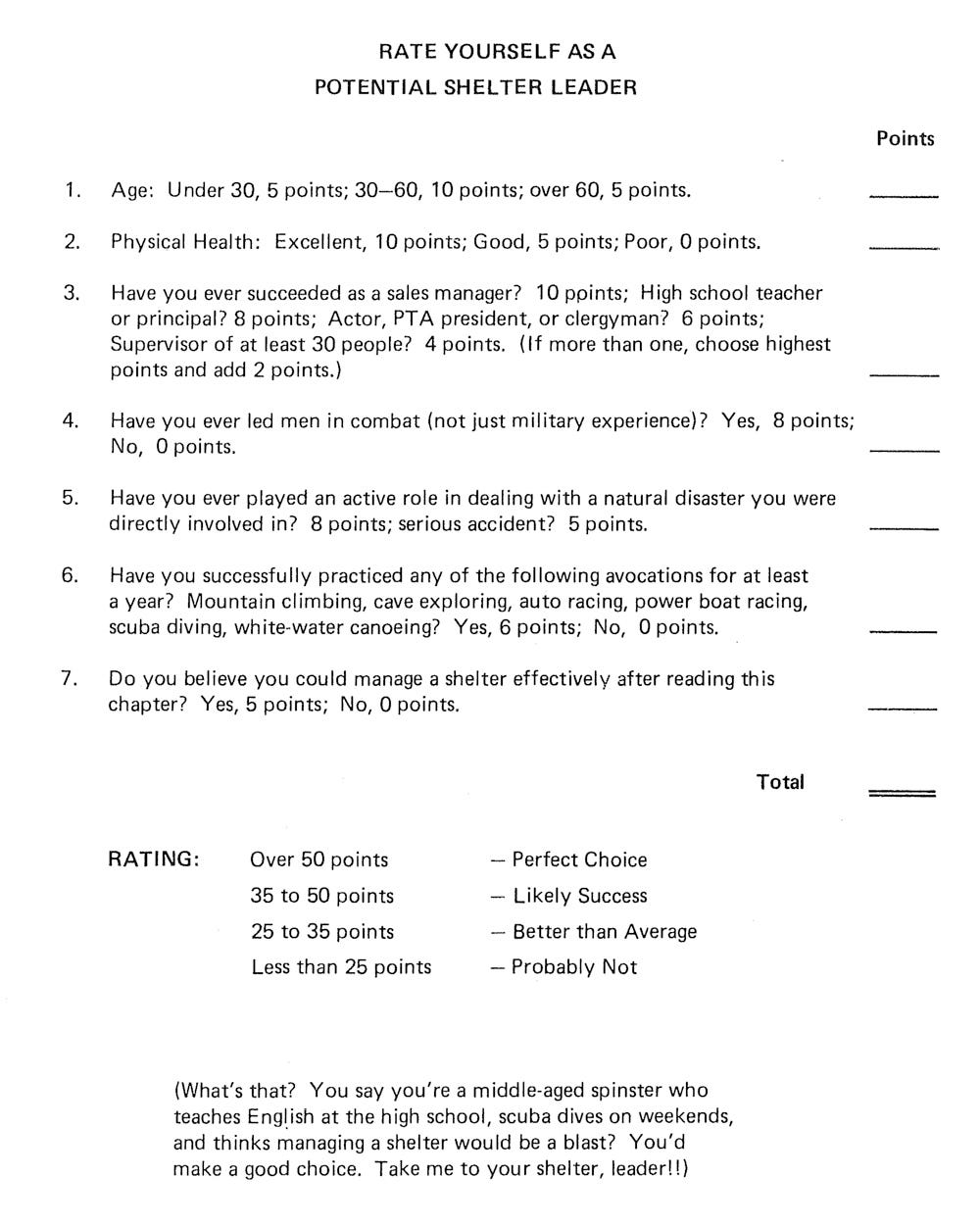

The DCPA Attack Environment Manual, also, conveniently, provides a “self-assessment test” so that you can rate your own effectiveness as a fallout shelter leader. I have reproduced it above, and re-typed it below in its entirety, with some minor editing to make it easier to do at home. You can also download it as a PDF, if you want print it out and fill it out it as it was intended to have been. As you go through the quiz, keep track of how many points you get, based on your answers to its prompts.

RATE YOURSELF AS A POTENTIAL SHELTER LEADER 1. Your age: - Under 30 ...... 5 points - Between 30-60 ...... 10 points - Over 60 ...... 5 points 2. Physical health: - Excellent ...... 10 points - Good ...... 5 points - Poor ...... 0 points 3. Have you ever succeed at being a... (if more than one, choose the one with the highest points, and add 2 points.) - Sales manager? ...... 10 points - High school teacher or principle? ...... 8 points - Actor, PTA president, or clergyman? ...... 6 points - Supervisor of at least 30 people? ....... 4 points 4. Have you ever led men in combat (not just military experience)? - Yes ...... 8 points - No ...... 0 points 5. Have you ever played an active role in dealing with a natural disaster or serious accident you were directly involved in? - Natural disaster ...... 8 points - Serious accident ...... 5 points 6. Have you successfully practiced any of the following avocations for at least a year? Mountain climbing, cave exploring, auto racing, power boat racing, scuba diving, white-water canoeing? - Yes ....... 6 points - No ...... 0 points 7. Do you believe you could manage a shelter effectively after reading this chapter? - Yes ...... 5 points - No ...... 0 points RATING — TOTAL POINTS: - Over 50 points ....... Perfect Choice - 35 to 50 points ...... Likely Success - 25 to 35 points ...... Better Than Average - Less than 25 points ...... Probably Not (What's that? You say you're a middle-aged spinster who teaches English at the high school, scuba dives on weekends, and thinks managing a shelter would be a blast? You'd make a good choice. Take me to your shelter, leader!!)

Yes, that final parenthetical — with the two exclamation points!! — is in the original. It is interesting that, per the assumptions of the period, all description of shelter leaders in the text appears to assume that leaders will be male except the last line which invokes a “spinster” leader. I have to say that I would be deeply suspicious of anyone who would say that they think managing a community fallout shelter after a nuclear war “would be a blast,” though.

It’s an an interesting collection of questions. The one about “avocations,” a previous page indicates, is about demonstrating “experience showing tolerance to the stress of physical threat,” and the creators of the test believe that having chosen an avocation that “involves some danger or personal risk” is a good sign of that.

So how did you rate?

One of these requires you to read their chapter, but my little description above gives you some of the flavor of it. I also am not completely clear on what they mean by “played an active role in dealing with” in question 5, or what a “serious accident” means in this context. (I’ve called emergency services after witnessing a serious accident, does that count?)

Taking a very minimalist approach regarding my age, physical health, and interpreting “high school teacher” as having roughly analogous skills to that of a college professor, gets me easily into the “better than average” category, even without reading the shelter chapter, and I could even argue for a “likely success” with a few other interpretations.

Of course, I could always improve my suitability by becoming a race-car driver.

Today, these signs no longer have any real meaning and do not indicate that the space has any useful supplies, or even meets the construction standards it did when it was first identified, and the actual spaces have, in my limited experience, usually been repurposed and are kept locked. Many jurisdictions deliberately encourage removing these signs, as they would be misleading in an actual crisis. I have been in many of these “dual use” spaces in New York City — most of them are just basements.

Defense Civil Preparedness Agency, Department of Defense, DPCA Attack Environment Manual (June 1973), chapter 7. All shelter photos and text here comes from this source.

Sales managers ftw!

So the list of hobbies makes sense given the added context, but I am most puzzled about the rating of ideal jobs. You would think ‘high school principal’ would be up there with ‘sales manager’, and it’s equally interesting that ‘actor’ is the middle of the pack with PTA president and clergyman and still a category above actually being in charge of large groups of people.

I wonder if the focus on sales and acting implies some sort of expectation of deception or manipulation on the part of the leader?

Anyway, I don’t think calling EMS counts. I assume it means helping out with, or managing the response to, an industrial or automotive accident or they like. Based on the *serious* emphasis I think this would even mean death or maiming was involved vs just light injury.