Two generations of nuclear hopes and nuclear fears

A conversation with historian Zachary Schrag and his father Philip Schrag about their multi-generational encounters with nuclear threats

Doominations is a series of interviews with people whose life experiences or work in some way touches on the questions of interest to the post-apocalypse.

At a workshop last summer, I was got to talking with Zachary Schrag, a professor of history at George Mason University who has written a number of books, including the history of the Washington, D.C., Metro system, and, most recently, nativist riots in antebellum Philadelphia. At the workshop, we spoke about various nuclear matters, and he was sharing some of his memories with me about growing up in Washington, DC, during the Carter Administration. His father, Philip Schrag, is a professor at Georgetown Law, and was the deputy general counsel of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and a board member at Council for a Livable World. I thought it would be interesting to talk to both of them about their different generational experiences regarding nuclear war, and so I asked them both to allow me to interview them simultaneously.

Zachary: So I think I am generationally unusual in that a lot of Americans who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s had civil defense drills, had fallout shelters, had big scares like the Cuban Missile Crisis. And for most people of my generation born in 1970, that was less of an obvious presence.

We still had relic fallout shelter signs on some buildings. I remember one summer camp, one of the trash cans had instructions for how to use it in a fallout shelter. But I don’t think that most of my friends knew much about nuclear weapons. And I was unusual in that I did.

My father, starting in 1977, was trying to negotiate a nuclear test ban. He taught me and my brother a fair amount about the threat to us about things like intercontinental ballistic missiles and MIRVs and fallout and all of these kinds of things. And when he first took the job in the Carter administration, that was not terribly alarming because while there was this big problem out there that could kill us all, it was very clear that my father was going to fix it and we would live in safety ever after.

And then at some point, probably around 1979, it became clear that things were not going according to plan. You had the Iranian hostage crisis. You had the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. You had Carter’s decreasing popularity. And I became quite afraid that Ronald Reagan was going to win the presidency and lead us into nuclear war and we would all die. And worse than that, I thought we would die very horribly and painfully.

We did not have the World Wide Web and fancy sites like yours telling us how exactly we would die. But there were plenty of maps at the time. And for someone growing up five miles from the White House, I knew that I would be burned to death, which seemed pretty unpleasant. So again, this was, I think, for the most part, not well known among my peer group until 1983 when The Day After aired on national television, at which point my friends maybe caught up a little bit with me and my knowledge and fear.

Philip, how do you feel hearing your son talk about this?

Philip: Well, this is kind of a recapitulation of my own childhood experience. I was born in 1943 and grew up with the bomb. In about 1950 or 1951, I was in the third grade and all the Soviets had gotten the bomb and my classmates were scanning the skies for the Soviet bombers that were going to come and get us. There were air raid sirens up in our town and drills from time to time. And whenever the siren went off, I would become terrified.

And then in the third grade, there was a really big drill in which the teachers had to walk everybody home from the elementary school. And dropping off each in the group, dropping off each kid at his home. I lived the furthest from the school. So the teacher had to walk miles to all these houses to get to my house. And poor Mrs. Artister was very tired by this time she got to my house and my mother invited her in for a drink, which she gratefully accepted.

The experiences continued because there were drills all through junior high school. We had to go to the basement of the school. This was a few miles from New York City. So I knew even in the third grade that I would die if there was a nuclear war. And in the basement of the school, all of us knew that we would die and that this was a very silly thing.

It wasn’t until about high school though that we got the idea that we could express ourselves about how silly this was. And we started wearing black armbands in the basement drills to show our disaffection from the grownups’ efforts to calm us. This led to a series of actions on my part. One was that in the 10th or 11th grade, I was an amateur radio operator, and I joined our local civil defense group. And I have a little pin to show for it.

We had exercises in which — these were all high school students doing this — in which a group of people would hide a radio transmitter somewhere and pretend to be Soviet spies. And the others of us with portable receivers and homemade antennas made out of coat hangers would try to triangulate the location of the hidden transmitter and nab the spies. And the person who nabbed the spies became the spies the next month.

When it was our turn to be the spies, we actually dressed up as women and hid the portable transmitter in a baby carriage, and we were wheeling it down the streets. And finally, we were caught. But that was quite an adventure.

When I graduated from high school, my nuclear interests continued. And I joined Harvard College’s anti-nuclear group called Tocsin. And Tocsin led a nationwide march in February 1962. There were college students from all over the country who converged on the White House. And President Kennedy sent coffee out to all of us. And that made the front page of The New York Times the next day.

But there was a more serious effort as part of it. It wasn’t just marching. Individual, small groups of students were designated to meet with the leaders of US nuclear policy and try to argue sense into them — that nuclear war had to be prevented and not fought, that fallout shelters were a silly idea because we were all going to die in our fallout shelters. And there were, of course, stories about how people would shoot each other to get into their fallout shelters, and so forth.

My particular small group was designated to meet with Jerome Wiesner, Kennedy’s science advisor, in the Executive Office Building, in his office, and argue with him. And I was part of that delegation. It was the first time I entered the old Executive Office Building, and I was a student protester. We met with Wiesner, and did not change his mind.

And that was the last time that I entered the federal Executive Office Building until about 15 years later, when I was the Deputy General Counsel of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and had many meetings in that building trying to affect federal policy to stop nuclear testing, just as I had 15 years earlier as a protesting college student.

I'm struck by how, in both of your stories, you’re both describing having these very foundational experiences about nuclear fears: Philip, your reaction to the civil defense drills with the feeling that these are not going to do anything; and Zachary, you go from this position initially feeling confident, and then having this loss of confidence come in. How much did these fears shape your life paths?

Philip: It certainly affected mine. I was terrified as a high school student, and wanted to do something about the fact that everybody was terrified. And so when I got to college, I actually wrote my undergraduate thesis on nuclear negotiations that led to the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, which occurred while I was in college, increased my commitment to working in this field, although when I graduated from college and went to law school and graduated from law school, I didn't have an opportunity to work in the field because Nixon had been elected and there was little prospect that he was going to stop nuclear weapons testing or sign a nuclear weapons testing ban. So it wasn’t until Carter was elected that I actually had a chance to do something about this.

Zachary: And for my part, my anxiety peaked in the early 1980s and then diminished after Gorbachev came into office. And my experience again in high school and college was of one amazing thing happening after another, i.e. Gorbachev's initiatives. I was looking up some dates. It’s 1990, I believe, that an SS-20 shows up in the Air and Space Museum in downtown Washington. So, you know, one of the missiles I'd been afraid of is now there and is literally a museum relic.

I remember reading my senior year of college in 1991 that Boris Yeltsin had officially stopped targeting missiles at the United States. So I’d lived, again, aware since childhood that a Soviet missile was pointing at me at all times. And obviously I knew those missiles could be retargeted, but even the idea that Yeltsin was not actively trying to target and possibly kill me was a big deal! You know, again, in terms of my nightmares and psychological state.

The first Gulf War in 1990, where again, the Soviet Union under Gorbachev stood back, suggested that the US-Soviet rivalry was not central. And I actually ended up living in Russia for six months in 1993 after the collapse of Soviet Union. And, you know, obviously the Russian threat is back, but at the time it was a very hopeful time. So I did not feel I had to try to give my own life to nuclear disarmament.

What specifically do you both think, having both been made to fear nuclear war as children, about the value of, to put it bluntly, scaring children about such risks? There’s an argument that could be made that, whatever the value of Civil Defense from a practical standpoint, that it made the issue of nuclear war very “salient.”

Zachary: I had this weird fortune of not having any drills. I was too young for the nuclear drills and too old for the active shooter drills and so, you know for all of that I still had a fair amount of terror and nightmares. So I don't quite know what to say for that. I think that what I've read about the active shooter drills is that they provide kind of all the trauma our schoolchildren need without adding to that and it has not turned them into activists against assault rifles. Some of them, obviously, yes, but we still have a lot of assault rifles in this country. And so I’m not sure if that sense of terror is as productive as we might wish. Again, my sources of terror were more the artistic representations.

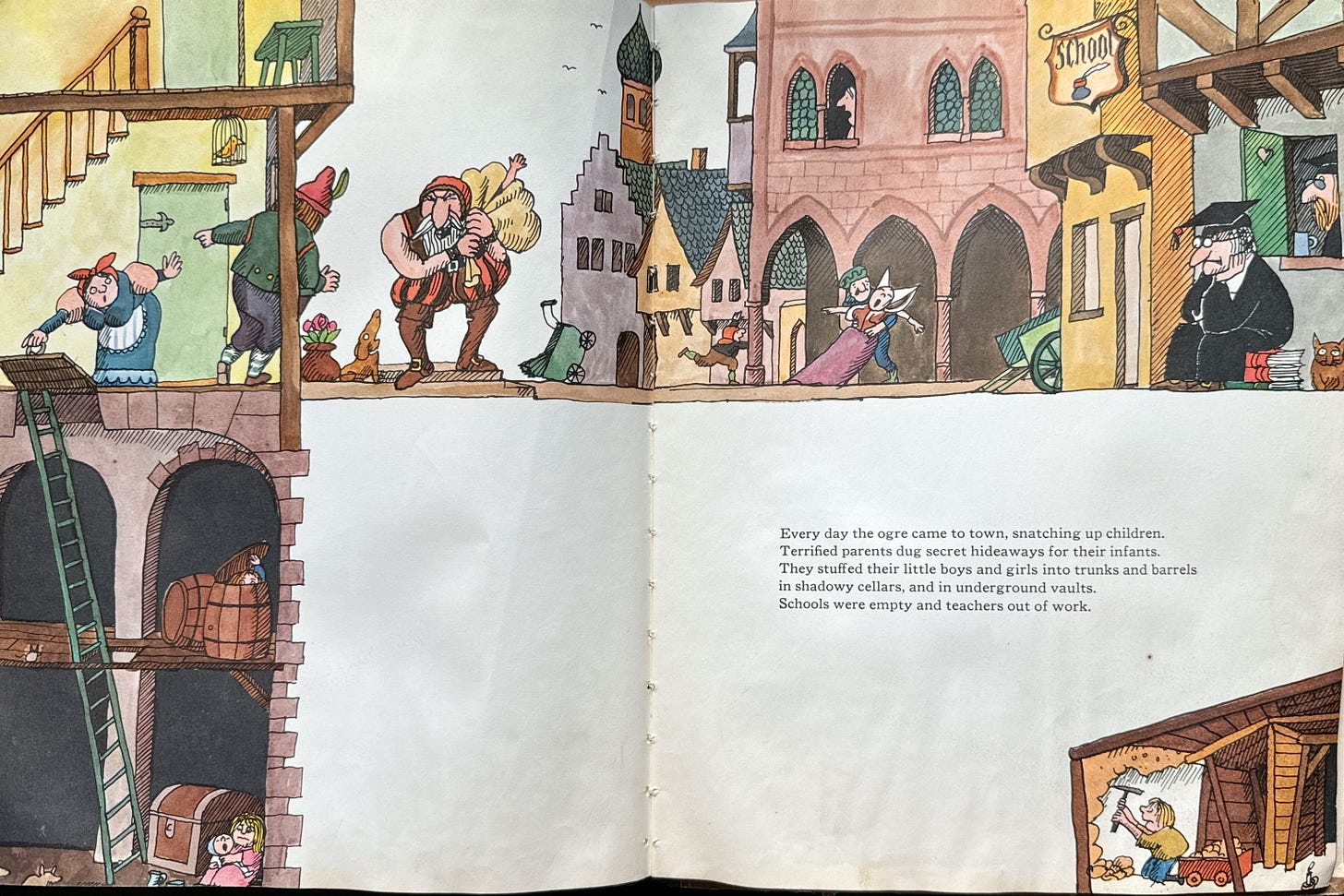

Nan Randall's Charlottesville story,1 which I pulled off, I think my father’s shelf around 1981, gave me very deep nightmares. My mother once told me that the book that I was most afraid of as a child was a book called Zeralda's Ogre by Tomi Ungerer. And she couldn’t understand if that was the scariest book, how the Charlottesville story could also be the scariest. And if you look at Zaralda's Ogre, it’s got this spread of the ogre coming to town, and all the children hiding in the basement, much like a fallout shelter. So in fact, they’re the same terror for me, this cannibalistic ogre and the nuclear weapons. Either way, you're trying to hide your children in the cellar, and someone's coming from you. And I learned many years later that Tomi Ungerer spent his childhood in Nazi occupied Alsace. So he had his own trauma to transmit.

I think, I guess my conclusion is that there’s plenty of trauma to go around. And whether it’s climate change or active shooters or nuclear threat, if we were really to “sensitize” our children to all the things that could not only kill them, but destroy the world around them, we would not have very effective children anymore.

Philip: Zachary, I'm so sorry that I wrecked your childhood twice, both with Zaralda's Ogre, and with the threat of nuclear war.

Zachary: Well, it's always something. I would not let my children read any Tom Ungerer. But I read to them The Wolves in the Walls by Neil Gaiman, and apparently that traumatized my kids just as effectively. Yeah, there’s going to be something that you think is a kid’s book and it turns out to be just a nightmare.

Philip: I don't think that nuclear weapons drills would be meaningful in today’s world. For one thing, there are two much more present and obvious threats to the survival of mankind as a species right now, like climate change and the increasing number of epidemics and pandemics. Even if the government or somebody encouraged nuclear weapons drills now, I don’t think anybody would participate. I think there’d be protests and jokes about them.

Given the challenges and threats the world faces, how do you guys cope?

Philip: I cope by doing a little bit of work with the National Center for Arms Control and Disarmament and the Council for Livable World. But other than that, I feel like there’s not much I can do either. I’m certainly not gonna hide in my basement.

Zachary: I have not found much of a way to address climate change. I am writing again about mass transit, which theoretically could help us find less energy intensive ways to live, though the more I do the research, the more pessimistic I grow about that. Again, I have succeeded in passing trauma onto at least one of my children, and maybe can continue with my nephew. My son is weirdly well adjusted, so I may have failed there. But in terms of telling my children that I am giving them a broken world and hoping that they can do more to fix that than I have.

One of the difficulties in talking with young people about these things is that if you don’t have some way to make them feel like they have agency, it easily encourages fatalism.

Philip: Well, in the United States, unlike many countries, we do have a way to exercise agency. And it’s not just by voting. It is by contributing money to candidates who have some solutions to these problems and knocking on doors in political campaigns and running for office oneself. It’s possible for people in younger generations to become activists and get politically involved. Politics is our way in a democratic society to affect social change more effectively than simply recycling your plastics.

Zachary: I would chime in with the classic Jewish wisdom that you are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it. And I think that does give us some time for Netflix in the evenings if we've tried to do something. And I find that with my own students, there is a certain amount of techno-optimism that they have, that maybe they can figure out better ways to do this. Some of that I fear is misplaced. But for all of the laments that we humanists have about the lurch into science and engineering fields among young people, I think at least part of that is that those young people are hoping to gain the tools not just to enrich themselves, but to repair some of the world.

A 15-page fictional story of life after nuclear war that was included in the Office of Technology Assessment’s 1979 Effects of Nuclear War.

Timely subject material given that I have a chance in the near future to visit This cold war relic:

https://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/falloutpostjg3.shtml

I'm not a child and I certainly don't want to play down Zachary's experience, but I fail to see how the Charlottesville story would be that traumatizing. It's certainly in the optimistic end by the standards of nuclear war descriptions, even for something written before people in the West knew about nuclear winter. It's so optimistic it literally mentions TV reruns as one of the problems people would be facing post-attack!