Famished barbarians

The very British fears of Sam Youd's The Death of Grass

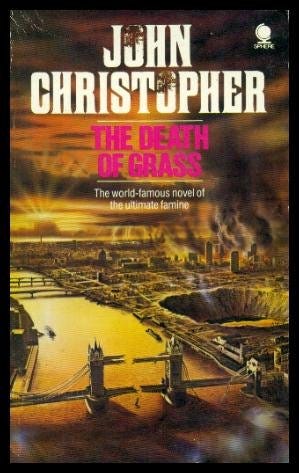

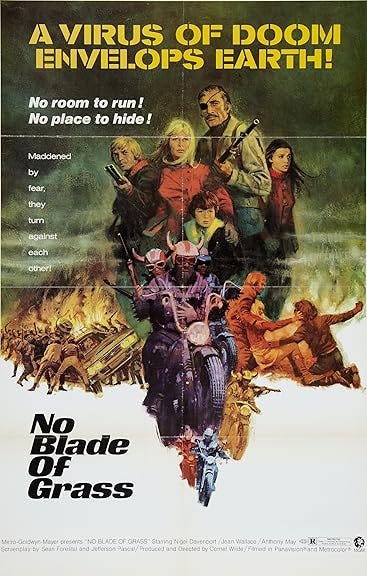

One of the odder end-of-the-world novels that I’ve read is Sam Youd’s The Death of Grass, first published in the United Kingdom in 1956 under the pen-name of John Christopher, and later published in the US as No Blade of Grass.

I first read the book while preparing to teach an “introduction to the humanities and social sciences” course for freshmen in 2018, on the subject of “The End of the World.” The organization of the course was around four “modern horsemen of the apocalypse”: nuclear war, food insecurity, global pandemic, and ecocide.1 Each of these units involved reading one novel, watching one film, and reading a number of academic articles. The hardest one to come up with the “fictional” components was food insecurity, as there aren’t as many everybody-starves works of fiction as there are everybody-gets-nuked or everybody-gets-sick or everything-goes-to-hell-because-we-killed-the-environment works. So I came across Death of Grass in this context: looking for a thought-provoking book to assign to freshmen. I didn’t end up using it, for reasons I’ll get into (I assigned The Road instead).2 But I ended up somewhat obsessing over it, and have now read it several times.3

I consider The Death of Grass to be a textbook example of what I think of as a “post-apocalyptic road-trip.” Things were normal. Then, the world fell apart. The plot requires the protagonists to get from point A to point B. Along the way, they see the ruin of the world, and undergo various challenges. They make it to their destination but — surprise! — it proves to be less of a refuge than imagined. Roll credits. The genre is a somewhat dark variation of the Hero’s Journey, where the traversal through the world leads to a lot of world-building opportunities as well as setting up an almost unlimited number of challenges to overcome, but often leads the characters through a sort of “anti-hero arc” rather than a traditional “hero arc.”

The specific “end of the world” scenario in The Death of Grass is unusual, and what makes it somewhat stand out of a very busy crowd. An agricultural virus is rapidly spreading through the world, country by country, rapidly killing any and all grasses.4 As this includes wheat, rice, barley, and animal stock, this has a massive and swift impact on food availability. Our protagonists, from London, watch this happening in Asia and then the European Continent with a muted apprehension that feels particularly British. Wherever the virus spreads, the food supplies rapidly dwindle, and is followed by riots and political collapse. Our British protagonists tut-tut at this display of incivility and, of course, we know that they are not long from this same fate themselves.

The book follows around John, his friend Roger, and their families (wives, children), as they try to cope with this situation. They get a tip-off that the virus has been found in the UK, but that the government is trying to keep it under wraps. They anticipate that London is going to fall to pieces, as have the capitals of other countries so affected, and so John and Roger conspire to sneak their families out of the city before any lockdown or bedlam goes into effect. Their goal is to reach John’s family farm, run by his brother and specializing in virus-free potatoes, which is away from cities and located in an easily-defensible valley.

Before they get out of London, they attempt to purchase a firearm from a gun store, but are thwarted when its owner, Mr. Pirrie, won’t sell them a weapon without a license. They attempt to use violence against him, but fail: he gets the upper hand on them, at which point they let him know the full situation. Pirrie agrees to help them — if they allow Pirrie and his wife to travel with them.

Their attempt to simply drive out of London fails, however, when the lockdown happens earlier than they anticipated. They get out… but only by murdering three soldiers in cold blood. Yikes.

They then proceed to retrieve one of their children from a boarding school — they muse on the fact that the school staff and the kids there are probably going to be in for a rough time — and then onwards to the farm. Along the way, they witness the full force of the famine and the subsequent decline in order, which includes such 1950s classics as the government nuking its own cities to reduce the number of mouths to worry about. The more time passes, the worse things get: they face robbers, bandits, and, well, worse. Murders, rapists, you name it.

But the real conflict, in a way, comes from within. What makes The Death of Grass a shocking read, even today, is not just how quickly their world falls apart — it goes from the tut-tutting to all-out, no-holds-barred social destruction in a matter of days — but how quickly the protagonists adopt a wholly rapacious, self-interested, eat-or-get-eaten worldview. They jump from “civilized” to “murderers” in one quick leap. And I use “murderers” purposefully: what they are doing is not self-defense in any true sense. They murder those three soldiers, just doing their jobs and ignorant of the broader circumstances, rather than explore or attempt any other possible options (alternative escapes, reason, bribery, etc.). They come across a farmhouse and shoot the adults in it in order to take their food, rationalizing it on the basis that if it wasn’t them doing it, someone else soon would. Their only bit of “charity” is that when they find that they had a teenage daughter, they agree to take her along with them. Great.

The text is pretty heavy-handed with this theme. The protagonists bellyache quite a bit about how they are transforming into monsters. They express remorse about not being able to really help anybody else most of the time. But they also eagerly and immediately embrace that they are living in a “new era” with new rules and new morality, where loyalties are tightly constrained along familial or transactional lines.

There are many villains to go around, but the amoral Pirrie is painted as the worst, because he doesn’t bother bellyaching, and is quite willing to abuse his new-found power as a-man-with-a-gun. He’s wily, wary, and a crack-shot, so he has value to John and Roger, but they don’t trust him very much. He reveals himself to be quite a monster, ultimately, “marrying” the aforementioned teenage daughter. The point being made appears to be that even in a world with a shifted moral spectrum, there is still a spectrum of sorts. But, of course, John enables Pirrie’s actions, because he both needs and fears him.

There are two things that jump out to me about the moral void they leap into. One is that they do not conform to the standard post-apocalyptic good-guy moral code at all. Yes, Mad Max kills a lot of people. But they’re usually all “bad guys”: they are raiders, killers, robbers, etc. They usually shoot first, or at least it is a reasonable assumption that they are going to shoot first. Mad Max doesn’t like, show up to an encampment of good-if-somewhat-hapless people and then wipe them out so he can get a meal. And Mad Max is not even the most selfless of the post-apocalyptic good guys! But he’s not, you know, evil.

But John is… pretty bad! And ultimately it ends up costing him a lot. But it is still portrayed, for the most part, as self-evidently what he needs to do. It does feel like a dreadfully cynical outlook being expressed by the author.

The other thing is the speed at which they descend. There’s an episode of South Park where, after getting trapped in a gymnasium during a snowstorm, a group of the town’s citizens immediately begin discussing the need to engage in cannibalism. And I think of that, sometimes, when thinking about what the appropriate interval of time is for throwing out one’s moral code in the event of social destruction.

When thinking about apocalypse in the abstract, it’s a dilemma of sorts: if you accept that social disintegration requires adopting a new moral code, at what point, or after what events, do you adopt that code? It is a question I’ve enjoyed posing to students. Only one or two have ever answered “never”: they maintain that they would prefer to maintain their moral code rather than survive, if it came to that. Most suggest an interval of time on the order of weeks. When I ask them why, it is because they are expressing an uncertainty about whether or not the social disintegration has actually occurred. They wouldn’t want, as happens in the South Park episode, to be found chewing on a human femur when the snow plow shows up. The tricky balance is acknowledging that the more time goes on, the fewer resources or opportunities they may have under the “new moral order” (e.g., to steal or loot), but that without adding some kind of time interval, they fear crossing into morally deficit territory prematurely.5

I don’t know what the proper speed is to do such things, if there is a proper speed at all — it depends both on whether one’s personal moral code would allow for such a thing at all, and the confidence one has that the circumstances do indeed warrant it. But the answer given in The Death of Grass — that one should jump into the moral abyss immediately should it feel necessary to protect one’s family — feels, well, a little wrong to me. But it’s provocative for just that reason, I suppose.

I was also struck by how, for lack of a better term, British the book felt to me. One doesn’t want to generalize wildly about the “national character” of stories and narratives — there are always counter-examples. But the “what if beneath our civilization, we’re all just a meal or two away from being savages?” feels like a very British preoccupation to me. It’s Lord of the Flies, it’s Darwin meeting the Fuegians. It’s a colonial (and post-colonial) fear: that the difference between the civilized people and the barbarians is no deeper than a coat of paint.

American post-apocalyptic fiction, by contrast, is often obsessed with a very different theme: the lone man surviving against the hostile world without any government help. It’s often about the rugged individualist who survives by their wiles and their guts, and it’s usually one part fantasy, even when it is supposed to be an intolerable world situation. There are, to be sure, works that deliberately subvert this, as well, but part of that subversion seems to be quite deliberately pushing back on exactly this cultural expectation.6

Can one make similar overly-lofty-yet-still-perhaps-useful generalizations about how other cultures handle the post-apocalypse in fiction? I assume so, though most of what I have read in the genre is either British or American in origin. (If anybody knows of worthy additions from other cultures — particularly those that have been translated into English! — let me know, I would be quite curious to read them.)

So why didn’t I assign The Death of Grass, if I find it so provocative and interesting-enough that I’ve read it a few times? Ultimately, there were a few reasons. One is that for the purposes of the class, I wanted something that felt like a true work of “Literature with a capital L,” and The Death of Grass was just a bit too obvious and pulpy for that purpose. Hence going with McCarthy instead. Another is that I did fear that the students would find it to be distressing without sufficient payoff. I don’t hesitate to give students texts that are designed to make them uncomfortable (again, The Road was the alternate!), but I’ve got to feel it’s worth it and this book just felt too slight for that. I found ways to bring the questions that I thought were interesting in it out into the class without requiring the students to grapple with its rather cavalier attitude toward murder and rape.

And, ultimately, what I find interesting about the book is how wrong I find a lot of it. A wrong book, in the sense that its author puts forward what I find to be a pretty unconvincing argument, can be useful for thinking something through, but isn’t where I’d recommend people start thinking about anything, just because if you don’t have anything to fall back upon, it can be pretty hard to see exactly why you don’t agree with the argument in the first place.

And, yes, before you ask: it was a little odd to teach such a course not so long before COVID hit, and the global pandemics section suddenly felt a little too on the nose. One interesting aside is that a discussion we had in the class was about whether the Japanese (and other Asian nations) were excessively “germaphobic” in their mask-wearing practices (the students concluded that they probably were not), and whether we could imagine the US adopting routine mask-wearing in high-density environments (the students concluded that it probably would not). When I taught a revised version of the course in 2021, I decided that we had all had a bit too much “end of the world” at the moment, and instead reworked it to be about “The Future” more broadly.

In retrospect, if I were doing it again, I might have assigned Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2015), though that could have worked for ecocide as well. The books I ended up assigning for each of the units was: nukes: Walter M. Miller Jr.’s Canticle for Leibowitz (1959); famine: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006); pandemic: Max Brooks, World War Z (2006); ecocide: Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993). For the famine unit, along with The Road, they also read selections from Malthus’s An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968), the United Nations’ World Population Prospects (2017), and several oral histories I found of survivors from famines in Ireland, Ukraine, and China.

To be sure, it is a pretty quick read. And I also found it a useful “template” in many ways for thinking about characters, circumstances, and moral quandaries that I wanted to use in the game.

The introduction to the Kindle edition that I read has a long discussion of the scientific plausibility of such a thing happening, as an aside. It calls specific attention to wheat rusts, a kind of fungal infection that, like the virus in the book, can spread very rapidly and cause massive crop damage. It particularly highlights Ug99, a particularly devastating strain of black rust that has been spreading to new countries year by year, raising a lot of concerns. Just if you were looking for something else to worry about.

And it is not entirely an abstract question! A very similar sort of thing happened in 2005, four days into the Hurricane Katrina disaster, when personnel at a New Orleans hospital euthanized four patients who they believed could not be kept alive and in good health for what they expected would be a much longer period of isolation than it ended up being.

One of the reasons I assigned Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, for example, is because it feels deliberately constructed (like much of Butler’s work) to push back against that idea, and I liked posing the question to students about what the post-apocalypse would look like if one did not (as most science fiction does) assume a white male protagonist. And the idea of “lone survivalists are really psychopaths, not heroes” is present in a number of works, such as David Brin’s The Postman (1986).

In to note here that Yout, as John Christopher, also penned the highly-influential post-apocalyptic YA series, THE TRIPODS, depicting humanity reduced to serfdom and agronomy after the conquest of Earth by aliens known as "The Masters".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tripods

(I'm convinced that L. Ron Hubbard ripped this series off and used the milieu and some other details for his own post-apoc, BATTLEFIELD EARTH.)

I'll suggest 2 post-apocalyptic books which take place in the distant future. "Riddley Walker" takes place almost 2400 years in the future of southeast England after a thermonuclear war in 1997 (the book was written in the mid '70s) and it is written in the English dialect of that distant time. The "expanded version" has a glossary which is helpful the first time you read it. This is a masterpiece by Russell Hoban

The second book is "Engine Summer" which takes place somewhere in North America at an undetermined future date, but probably two or three thousand years in the future. To say anymore would involve spoilers. It is by John Crowley.