Why Oregon? Why 1983? Why a game? Why anything?

On the motivations behind the Oregon Road '83 game project

As I’ve mentioned before, what is now Doomsday Machines started out in my mind as a development blog (“devblog”) for the Oregon Road ‘83 video game that I’ve been working on. As with all things, it then expanded in scope and ambition, but basically most of what I am doing on here has come out of this prolonged “steeping” of my thoughts in the act of creating a post-apocalyptic landscape of my own. So I thought it would be worthwhile, and hopefully interesting, to talk a little bit about the origins of Oregon Road ‘83.

In a nutshell, Oregon Road ‘83 is a video game in which you play as a survivor of a full-scale US-Soviet nuclear exchange in the fall of 1983. In the game, you are tasked with traveling from Independence, Missouri, to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, in the weeks after the war. In the process, you will need to find adequate resources to continue your journey (you have limited food and fuel), keep track of your radiation exposure (you have a Geiger counter and dosimeter), and navigate the roadways and cities of this new, damaged Western United States. You’ll meet people of different backgrounds and experiences, some of whom mean you well and some of whom mean you ill, and will have to make hard choices about how to spend your time, your resources, and what kinds of situations you are willing to get into.

The gameplay is half Oregon Trail and half Choose Your Own Adventure book. The world is, as much as I can do it, a “grounded” depiction of what I think such a world could have looked like, based on a reasonably plausible Soviet “war plan” and capabilities and what we know about the state of the US survival plans, but obviously there is a lot of room for interpretation as to what these things would mean in reality. By setting the game several weeks after the actual attack, we avoid a game that is just about the immediacy of The Day After, where the fallout radiation has decayed to less acutely-dangerous levels, but before any kind of “post-nuclear order” has really crystallized.

So that’s the premise. But why do this, at all? Why Oregon? Why 1983? Why anything?

The immediate idea for Oregon Road ‘83 came to me in 2015. N Square, an NGO that I had worked with for awhile, launched a video game design competition for games that would raise awareness about nuclear security issues. I thought it was an interesting challenge. How do you make a game about nuclear weapons that does not fall into the control fantasy? The most obvious approach, it seemed to me, was to make a game that was from the perspective of nuclear survivors, not nuclear war planners. There are, of course, some nuclear war survivor-based video games — notably the Fallout series, which I was very familiar with. But Fallout is deliberately silly and makes no attempt at accuracy, and as a consequence (for better or worse) has essentially no educational value that I could see.

What would a more grounded, realistic video game about the aftermath of a nuclear war look like? This was the line of thinking that started me on this path. What then game to mind for me was a joke I have been making for years when teaching about nuclear war and nuclear fallout. I’ve long been struck by this graphic from a 1990 FEMA report showing one hypothetical late-Cold-War fallout pattern:

When I teach with this, I use it to point out what the consequence of having so many dense missile fields in the midwest are for those who live downwind of them, as it was assumed these would be targeted by Soviet forces quite densely and with fallout-producing ground bursts. The above is of course based on somewhat speculative ideas about what the Soviets would target and how, and the report takes pains to point out that the fallout distribution would depend on a number of metrological conditions, including wind patterns. So it is just a “sample” pattern, as it says — not a definitive prediction, but something to give you a sense of the nature of fallout as a threat.

An obvious joke to make when looking at this image is to point out that clearly, the correct interpretation of this map is “move to Oregon,” as it is the only state that is totally untouched by fallout. Oregon does not, in fact, get off scot-free from FEMA’s hypothetical nuclear exchange, but benefits from the fact that the targets that FEMA believes it may have contained were few and far between, probably targeted by airbursts, and because of its location in the northwest, favorably disposed to avoid the fallout plume from Seattle.

This map came to mind when I was thinking about the game proposal. From there it was an easy and immediate jump to a game that was basically an adaptation of MECC’s Oregon Trail (1985) but for a post-nuclear world.

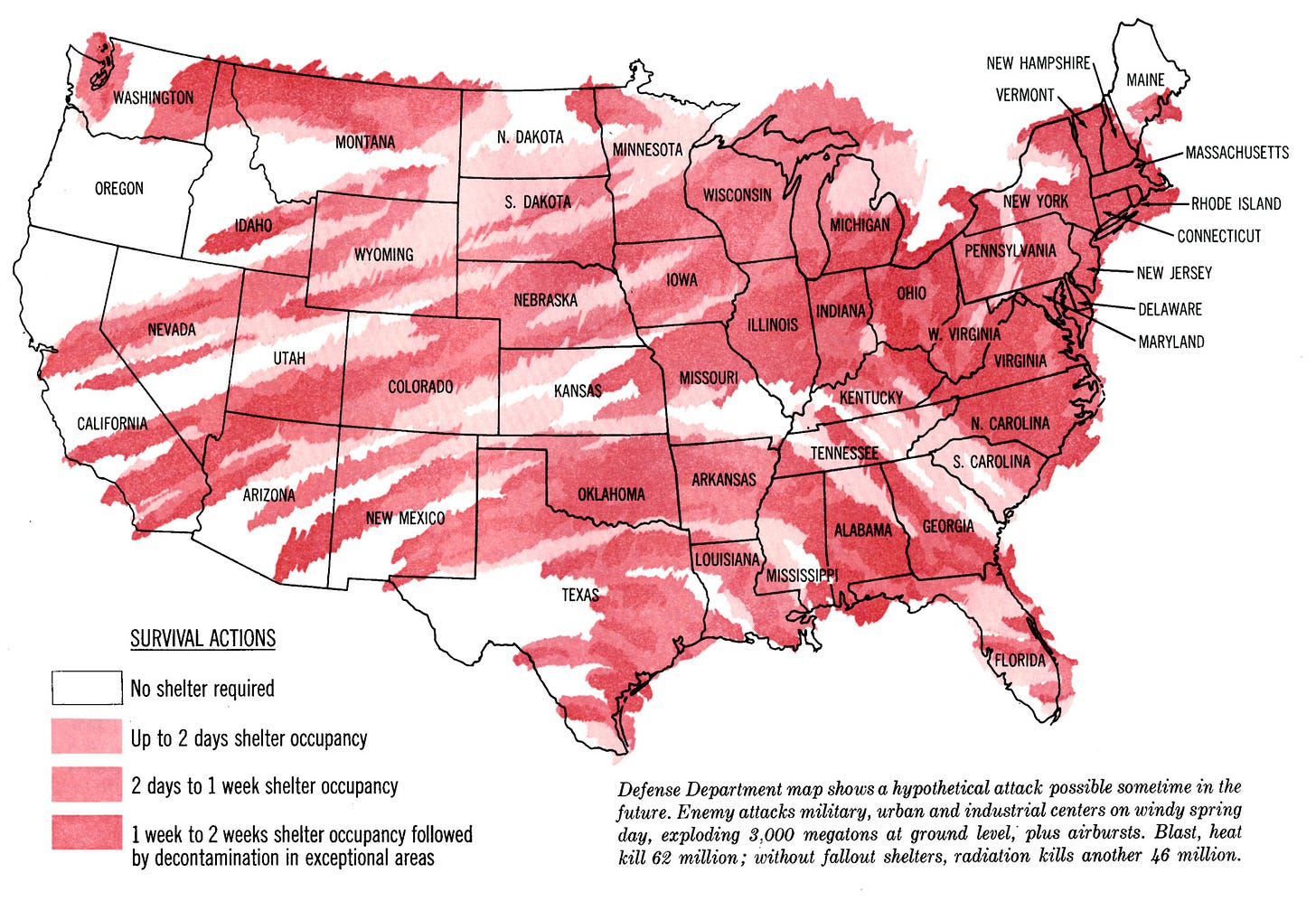

But which post-nuclear world? The post-nuclear world of 2015 would have looked very different from the post-nuclear world of the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), for example: different targets, different capabilities, and a different America. Here is a similar sort of fallout map from 1963, as adapted from a Department of Defense graphic by the Saturday Evening Post:

This particular map is based on a very different set of targeting assumptions — a Soviet arsenal of very different composition, and a United States with no vast missile fields, yet. They also clearly assume (rightly or wrongly) that there would be far more surface bursts assumed than the FEMA map.

If one is basing a game on Oregon Trail, then it made aesthetic sense to base the game’s nuclear war in the 1980s as well, I reasoned. This also aligned very well with more historical considerations. The early 1980s was a period in which the US and Soviet Union were in a state of strategic parity, more or less. While a lot of people seem to imagine that the arms race was always a somewhat “matched” thing, the US had a huge nuclear advantage over the Soviet Union until the late 1970s, in terms of number of nukes and capability to deliver them. Whether this “matters” (if they can still nuke most of your major cities, what does it matter that you can also nuke their minor ones?) is a separate issue, but the point is that a nuclear war in the 1980s is probably as “bad as it gets” in terms of damage to the United States.

This was not lost on the people living at that time. Consequently, the early 1980s in particular was a renaissance of sorts for cultural productions about or containing nuclear war: The Day After (1983), WarGames (1983), Threads (1984), Testament (1983), Terminator (1984), to just name some of the more iconic films. 1983 is when the idea of “Nuclear Winter” was first published (in Parade magazine, of all places); it is was when a West German pop song about an accidental nuclear war, caused by a faulty early warning system, could reach the top 10 internationally. It was when “Survivalism” — the predecessor to modern “Preppers” — hit its peak.1 Some of the largest public protests of all time took place against nuclear weapons in the United States and in Europe, because of the perceived threat of imminent nuclear war.

It was also a very dangerous period, historically. Historians today tend to consider 1983 one of the “close call” periods for the possibility of nuclear conflict, ranked perhaps just underneath the Cuban Missile Crisis. The conditions were tense, and the technologies and organizations underneath it all (on both sides) were error-prone. The Soviets feared that the US might have the capability for a decapitating nuclear attack that would preclude any attempt at retaliation, and (to debatable degrees) were worried that Reagan intended to do such a thing. They built a massive, deliberately hair-trigger nuclear arsenal, and kept a finger hovering over the metaphorical button. They scoured not only the skies, but newspapers and stock prices and other complicated sets of data, for signs that the US was preparing to make a move.

The US was seemingly oblivious of the seriousness of their concern, and did many thing that encouraged these fears, like deploying fast, accurate Pershing II missiles in West Germany (which the Soviets feared could target Moscow), and conducting a large-scale, more-realistic-than-usual NATO exercise simulating what they would do if they were initiating a nuclear attack against the Soviets. Against this backdrop, “normal accidents” happened: a Soviet early warning system thought sunlight reflecting off clouds were incoming missiles; after repeat airspace incursions by US military planes, the Soviets accidentally shot down a South Korean civilian airliner.2

One can (and some people do) debate how “close” any of this came to war, but my own sense is that it certainly came closer than most people realize, and that it is very easy to imagine a world in which nuclear war was precipitated in this period. There are, I think, deep historical lessons from this period about the nature of risk of nuclear war, about the dangers of raising tensions to a fever pitch in a world of sufficient complexity, whose technological capabilities and limitations were both extreme — missiles whose flight times were measured in minutes, but for whom detection of launch was fraught with false positives on both sides.

So, to return to the game, setting a post-nuclear apocalypse game in 1983, based on a game that came out in 1985 (Oregon Trail), seemed to me like a pretty natural thing. Setting it in the early 1980s would give me a lot to “work with” in every respect. It also added a little historical distance from the present, which felt useful. It could be retro but still relevant. As an educational tool, it could do a lot of potential “work,” both as a work of “history” (even if it was a form of counterfactual history, the nuclear war that did not happen) and as something that was oriented around the realities of nuclear weapons and their effects. There would be no giant radioactive ants, no super-mutants, no people living in fallout shelters for centuries, etc. This would be as “grounded” as one could try to make it, at least within the limits of my imagination and my judgments of what was plausible, as someone who studies this stuff for a living.

So that was the pitch. I called it Oregon Road as a deliberate homage to Oregon Trail and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. I later added the ‘83 because it coded its retro-nature better, and made it slightly more intriguing on the face of it.

But my pitch didn’t get funded. It got an honorable mention, which I did appreciate. I did not take it hard; I was busy enough, and the fun part was thinking it over and writing it up. In retrospect, I’m very glad that it didn’t get funded, because the game I proposed would have taken a lot longer to make than was plausible, and would have been much more limited than the game I have been actually making. There is no way that the game company N Square had contracted with (who would have had to, you know, finish on a deadline and pay employees) would be able to build out what I had in mind in the time they were willing to commit to it. If it had been completed at all, it would have been massively truncated and of much lesser value and interest.

But the idea for the game stuck in my brain for several years. Over that time, I read more about game development, made connections with people in the educational-games “world” (like Games for Change), co-taught a course with the dubious title “Video Games for Civil Defense” with a game designer, watched about a zillion “game design” YouTube videos of varying quality, and started a couple other, smaller-scale game projects which did not get beyond the initial planning/proof of concept stages, but allowed me to get my feet wet, as they say, in what is involved actually making a game and the often quite organizational difficulties in coordinating the different kinds of work involved.

My university has a couple extremely “honors” programs that are essentially meant to lure high-performing students to enroll here and not elsewhere. Among the “perks” they get is a stipend to work with professors on research projects over the summer. The professors gets nothing but the students’ labor (and we are not paid in the summers by default), but I’ve been hosting such projects for years because, unlike grants from other parties, it allows me to employ students to do weird, exploratory, and otherwise “risky” endeavors. The honors program doesn’t really care about any “deliverables,” they just care about the student having an interesting and hopefully enriching experience, so if we set ambitious goals and don’t meet them, it doesn’t really matter most of the time. Many of the projects I’ve started with these kinds of summer projects eventually evolve into later, externally funded projects, because they give me the opportunity to explore the “space” of something before committing to it. And even those that appear to come to “nothing” often turn out to be useful experience later, or at least help me rule out some idea as impractical.3

During COVID, all of these research programs went online and remote. I had the realization that a video game project could be an ideal remote summer research project. Video game development requires a lot of different skills which have to interact and come together: overall game design, writing, artwork, programming, music and sound, and, in the case of this kind of game, research. Give me an enthusiastic student, of any background or skill set, and I can find something for them to do on such a project. Most of the individual work is remote anyway, and coordinated through things like shared drives, Github, and so on. Meetings on Zoom are a drag, but we’d gotten used to them.

So each summer, starting in 2021, I’ve had groups of students, of various sizes, working on the game. It’s gone through a number of key changes, in terms of its technical backend, its gameplay, its story, etc., which will be subject of future posts. Most of this has been funded through my university’s Pinnacle and Clark honors’ programs, but the Outrider Foundation also provided some funds to give me a little more flexibility in hiring students.

We’re very close to a playable alpha — if you’re interested in playing it, just stay tuned here, as we are getting close to a dedicated game website where people can enroll to try it out. The exact timeline is as appropriately squishy as you would imagine from something that is very much an amateur labor of love, but it’s happening, it’s happening. If it wasn’t, I would be keeping quiet about it!

So why do this? This isn’t a traditional work of academic history, obviously. I do a lot of things other than what counts as traditional works of academic history, of course. And I am tenured, so I can do anything, or nothing. I’ve learned a lot of “traditional academic history” things in the process of working on this, to be sure. I am also interested in games as a form of education, as noted. But it’s also scratching a creative itch for me. It’s a project that is at a fascinating midpoint between fiction and non-fiction, a historical world that didn’t exist, but could have. I struggle to articulate what it is that feels so special and unusual about working that space, and how different it is from, say, writing works of non-fiction (which are, to be sure, also works of creativity). It’s a fun challenge — even if it involves creating a very un-fun world.

And a lot of them, it turns out, lived in Oregon! Which plays a big role in David Brin’s post-apocalyptic novel, The Postman (1985), which is also set in the Willamette Valley. I’ll write more on Oregon as a setting at some point, but it turns out to be a very useful setting for a lot of reasons that I later discovered.

There is an ever-growing literature on the nuclear “close calls” of the early 1980s. I think that David Hoffman’s The Dead Hand (2009) is a great starting point, though it talks about a lot more than just this. The National Security Archive has an impressive collection of documents on the “1983 war scare.” There are some who feel that aspects of this have been over-emphasized or exaggerated; as with all things, it’s possible to make that claim, especially if one dissects details. I think on the aggregate, though, the overall impression is of a very, very dangerous period, on par with the early 1960s.

Linus Pauling is variously quoted as saying something like: “The way to get good ideas is to get lots of ideas, and throw the bad ones away.” Which is something that resonates with me and my approach. The work it takes to distinguish between a “good idea” and a “bad idea” is often considerable. So a low-stakes summer project that helps me do that is highly valuable to me, even if the result turns out to be negative.

With respect to the Rajneesh cult in Oregon that Alex mentioned in his wrap up, just a thought...

I think it entirely likely that Jonestown, Synanon, Rajneshpuram and others were all started with good intentions but the inevitable Cult of the Leader (and a certain enforced philosophical narrowness and rigidity) eventually morphed them into something other than a positive influence. Or far worse. The Soviet Union - a product of 19th century utopianism and a reaction to an unresponsive and exploitative nobility- bled its peoples and failed exactly in that way. But at its heart was the idea of building something new and better. Even something as odious as Nationalist-Socialism in Germany had its utopian aims but only for a narrowly defined "in" group. And, of course, it had no real philosophy or theory of governance - there was no body of reasoning (economic or otherwise) to draw on - just the whims and musings of a Leader of the worst stripe.