Not a drop to drink

The plausible eco-horror of Paolo Bacigalupi's "The Water Knife"

While arguably one of the oldest forms of speculative fiction (thanks to the Tambora eruption), “climate fiction” has emerged as a sub-genre of its own right in the last decade or so, as part of both the growing salience of climate change and the accompanying broader understanding of the important impact that the natural environment has on the past and future of human civilization. Along with its frequent “call to action,” motivation, my sense is that part of what “cli-fi” is often intended to accomplish is to draw the reader’s eye to the ways in which we in our modern world take so much for granted about the favorable conditions for existence that we currently have, and how precarious those can be.

One of the most arresting books I've read in modern speculative fiction is Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2015). The basic concept of setting is easy to explain, in principle: What happens to the American West if the water runs out? The book’s characters takes pains to indicate that this is not really a matter of if but probably a matter of when, with repeated references to Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water (1986, updated 1993), a work of history that describes exactly what enabled the American West to be so inhabitable and agriculturally productive in the first place — mostly massive, New Deal water projects — and the ways in which the entire foundation of the American West is built on what is fundamentally a wasting asset.

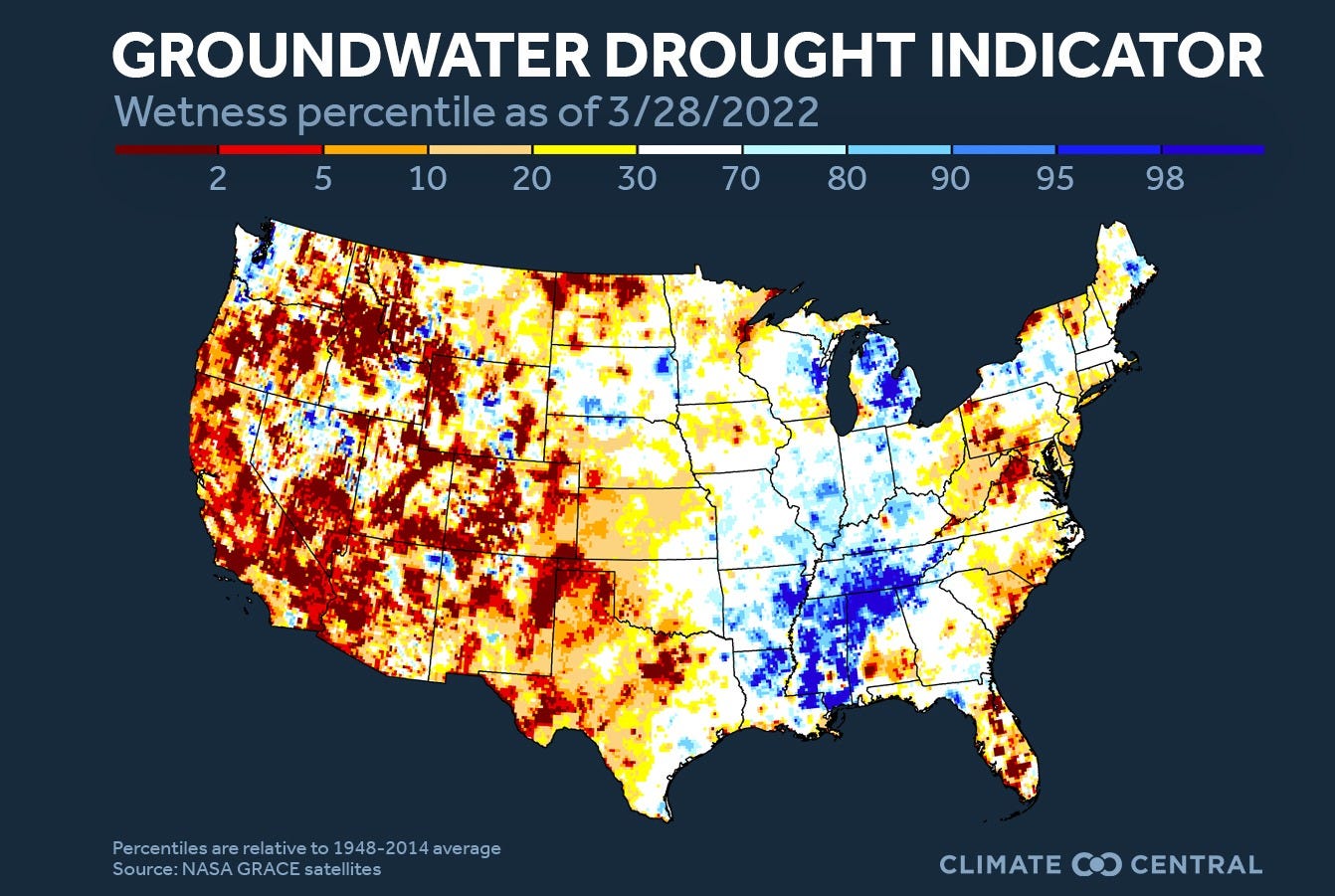

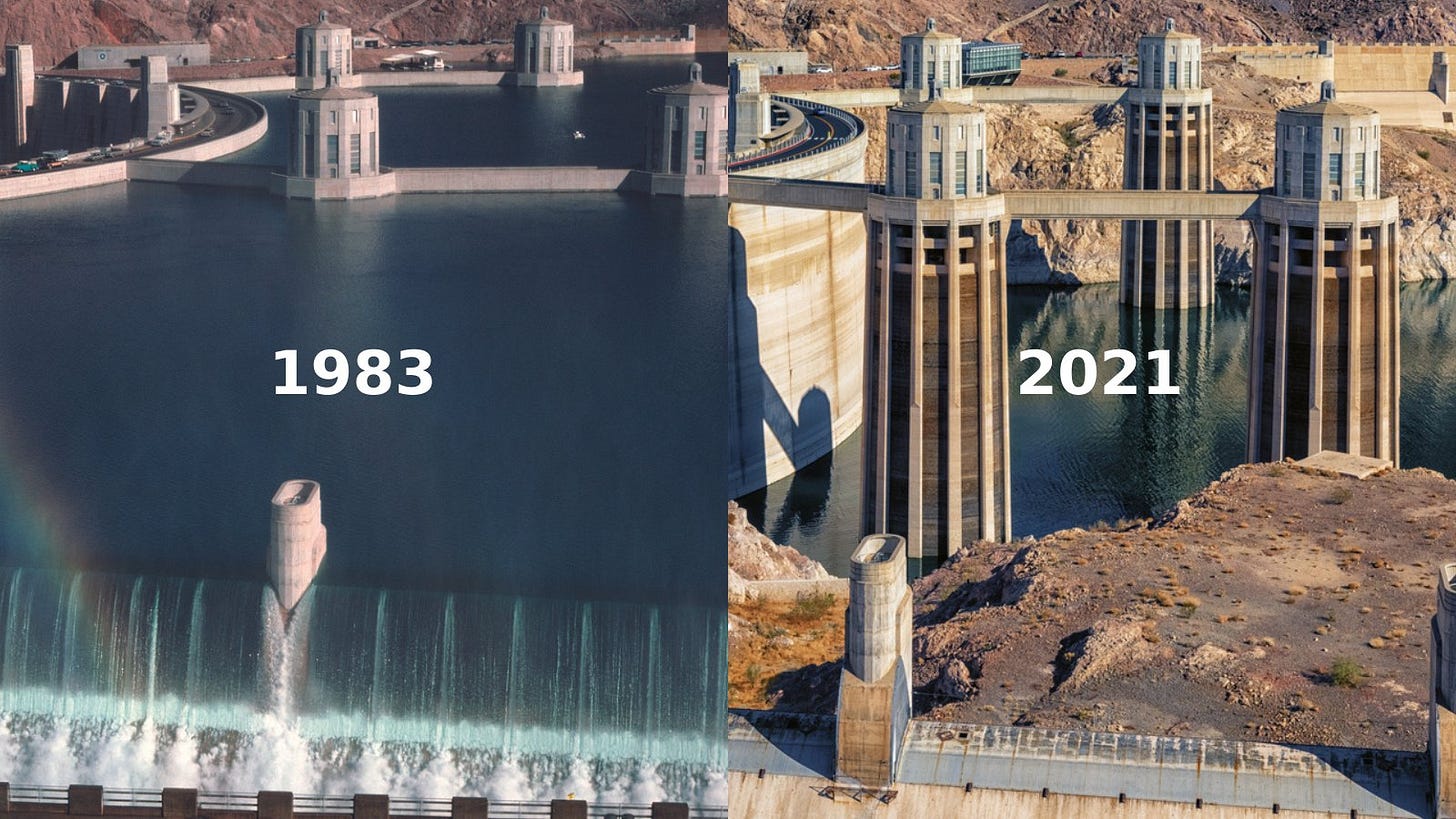

I was inspired to read Reisner’s book after reading The Water Knife, and found it compelling and astonishing. I grew up in California’s San Joaquin Valley, which is simultaneously one of the most agriculturally-productive areas of the United States but also one of the most dependent on the water-works that Reisner describes. Growing up there, I was aware that agriculture was a key industry, but I had no idea that all of that agriculture was due to water availability that was fundamentally artificial in nature and relatively recently (e.g., within the last century) enabled. Reisner’s book also makes a compelling case that the projects to move water around the West are mostly maxed out (there are only so many rivers to dam and manipulate), the amount of replenishable water available cannot sustain the large populations and intensive agriculture currently being used, and the difference has been made up by drawing from aquifers at rates that vastly outstrip their ability to “recharge.” The dream of making the desert bloom was a compelling one, but any progress there would be both limited in what it could support, and temporary.

So what does that mean for the tens of millions who live in the states and cities that the water enables, when the water runs out? That’s what The Water Knife is trying to explore. And, in a way, it’s much worse than some of the more dark post-apocalyptic books, like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, because it combines plausibility with a sense of inevitability.

Without getting into the specifics of the plot (because I don’t want to spoil a book that in my experience most people have not read, but might find worth reading), I want to just talk about the world that Bacigalupi imagines.

First, the water doesn’t just “run out” in some kind of apocalyptic suddenness.1 This is in the category of a “slow disaster,” or a “slow apocalypse”: a death by a thousand cuts, with no clear “inflection point” or moment of terror.' I will be writing more on this “slowness” and is relationship to climate fiction at some point in the near future, but it is, I think, one of the things that distinguishes climate apocalypses from, say, nuclear apocalypses. So instead of imagining the water “running out” as a moment in time, imagine it as a process that unfolds, bit by bit, over decades, with little harbingers and local-scale consequences popping up here and there, individually uninteresting except to those affected by them, but adding together into something that fundamentally reconfigures the West.

Bacigalupi’s book imagines that this will coincide with (and possibly contribute to) a decline in federalism in the United States. The tension between the autonomy of individual states (like California) and centralized control by the federal government has been present from the beginning of the nation, and of course has had moments of tremendous conflict (including the Civil War), and the world of The Water Knife finds the federal government having essentially exited certain key arenas of policy, and letting the states (sometimes literally) fight over them as autonomous political entities.

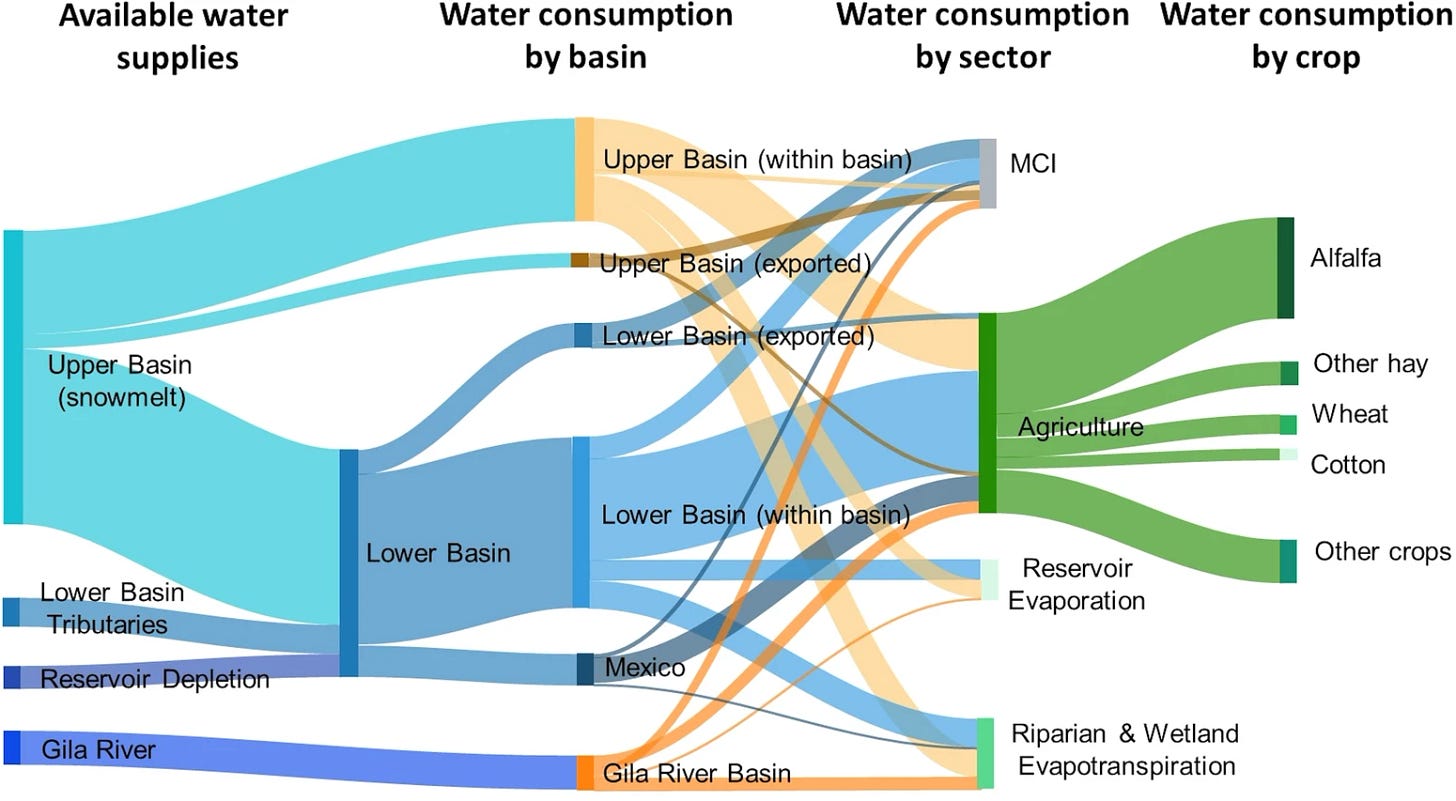

There are two domains where this really comes into play in The Water Knife. One is the nebulous legal area of “water rights”: the Colorado River passes through five states, and finally crosses into another country, Mexico. What obligations do states up-river have to those down-river, in terms of how much water they can divert, how much wastewater they discharge into it, and so on? At the moment, these sorts of things are arbitrated by agreements and federal oversight, to some degree; in The Water Knife, it has become a near free-for-all, with states conducting covert wars against one another to secure or sabotage the precious river water.

The other area is that of internal migration and internal refugees. Some states, because of their lack of access to direct water sources, get hit the hardest when the water “runs out.” Arizona and New Mexico, in Bacigalupi’s book, end up in pretty desperate straits, and end up with entire urban areas that simply cannot supply the basic water needs for their populations. When the water gets shut off (or prohibitively expensive) for a city, people can’t survive there long, and so understandably try to move to the places that do have water. But the states with water don’t necessarily want tens of millions of people — especially those who are quite poor, made even more so by the fact that any property they had in their previous areas of residence has become worthless — showing up as their new “water refugees.” And so internal migration is shut down, with (again) the federal government refusing to intervene to enforce freedom of movement.

I wish I found the above totally implausible. I think about the latter aspect every time I see the intense anti-immigration and anti-refugees sentiment that some people in this country have (despite nearly all being descended from immigrants, and many being the descended from refugees), and seeing the way in which many Americans are perfectly willing to extend outright scorn to the entirety of residents of other states (a sentiment not helped by living in New Jersey, which engenders a negative reaction in vast disproportion to any negative qualities it or its residents have). I find it entirely plausible that Americans in the near future will find themselves at the mercy of their own countrymen, and find them shockingly ungenerous in dispensing it.

And so this is what I find so utterly disturbing about The Water Knife, this marrying of a plausible future state of the natural world — the water problem — with a plausible way of it being adapted to by societies — a political problem. The world it creates is perhaps not totally “post-apocalyptic,” in the sense that civilization is wiped out, but it is definitely something different, something terrible, something that certainly doesn’t feel like it is part of the current world.

There has been a drumbeat of news coverage about water running out in various locations over the last few years, and increased attention to water availability as a salient and very near-term climate problem, one whose consequences are only just being appreciated. There’s so much news of a dark nature these days, though, that it’s hard to give one’s attention to any one piece of it, or even imagine what futures are possible.

The Water Knife doesn’t offer any “solutions,” really — it is not that kind of book. Its characters have very little agency over anything other than their immediate surroundings. What it does, though, is offer up one possible, plausible, awful vision of the future, and that provides a very useful organizing principle for making sense of all of these news stories, and what darkness they might portend.

I am putting “run out” in quotes because it isn’t as “final” a matter as just having “none,” it is more a matter of many different people, companies, states, etc., having certain needs and requirements for water (both quantity and quality), and then acting upon those requirements not being met in ways that impact the availability for other people, companies, states, etc. So the world of The Water Knife still has water, it’s just that its scarcity has created all sorts of new conditions, including conditions that locally induce even more scarcity.

"I will be writing more on this “slowness” and is relationship to climate fiction at some point in the near future, but it is, I think, one of the things that distinguishes climate apocalypses from, say, nuclear apocalypses."

I look forward to this; the psychology of handling sudden disasters vs. slow-motion disasters is quite important, I think. (For example, how people respond to hurricanes hitting Louisiana as opposed to creeping salinity in the soil.) A related piece of psychology that I think matters too: averting nuclear apocalypse means avoiding doing something that we haven't done, whereas averting ecological apocalypse means stopping something that we ARE doing. In both cases I think the "it's already happening" aspect leads people to downplay the situation.

Thanks for the recommendation. I wasn't overwhelmed with Bacigalupi's "The Windup Girl" but I may check this one out.

Eh, if you actually study water policy, the whole Southwest urban depopulation apocalypse scenario falls apart fast. The vast majority of water goes to agriculture, mainly because water law is weird.

Prices for water skyrocket due to depletion, who can afford it? Cities. That was the entire point of Cadillac Desert. Water flows to money. If they have to, big cities will build nuclear power plants and desalinate while the countryside withers away.

If humans haven't abandoned Saudi Arabia and the UAE, somebody will always finding a way to live in Phoenix. The inherent flaw in most apocalypse fiction is that it presumes total depletion of a critical resource. Meanwhile, people eke out an existence on the front lines in Ukraine. Somehow.