What would a faithful World War Z adaptation look like?

Is it possible to make a serious, thoughtful movie about global disaster and recovery?

Max Brooks’ World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (2006) is one of my favorite apocalypse/post-apocalypse/disaster novels. By taking a Studs Terkel approach to the zombie-apocalypse genre, it completely re-centers it around different questions than most zombie stories — and most post-apocalyptic stories in general.1 By lacking a central protagonist, instead looking at the impact of the titular “zombie war” as it played out in different nations and cultural contexts, kaleidoscopically exploring the fictional disaster’s impacts from the deepest depths of the sea all the way up into Low Earth Orbit.

And beneath the zombie facade is a deeper message, one about how global catastrophes and problems are (and aren’t) really solved. It’s a book that’s about how the solution won’t be found in a central hero, a miraculous discovery, or a technological fix. Rather, it will be found in carefully analyzing the nature of the hazard itself, and collectively working towards a slow, tedious, but ultimately successful solution.

And that even when you “fix” the problem, you haven’t really ended it. Even when the “solution” is identified, it’s a long, hard slog to implementing it, and the world is irrevocably changed in many ways. You can’t go back, the book makes clear, but there are different paths going forward, some better and some worse than others.

Sound familiar? Yeah. Aspects of this book hit differently since the pandemic, because its central zombie metaphor is very disease-based. The zombie genre is always an analogy, metaphor, or commentary on something, and what I appreciate about Brooks’ book is that it is a commentary on how society deals (and fails to deal) with large, systemic, overwhelming problems. I don’t know which of these Brooks had in mind while writing it, but prior to the pandemic I tended to read it in the light of climate change. Today it feels a lot like COVID.

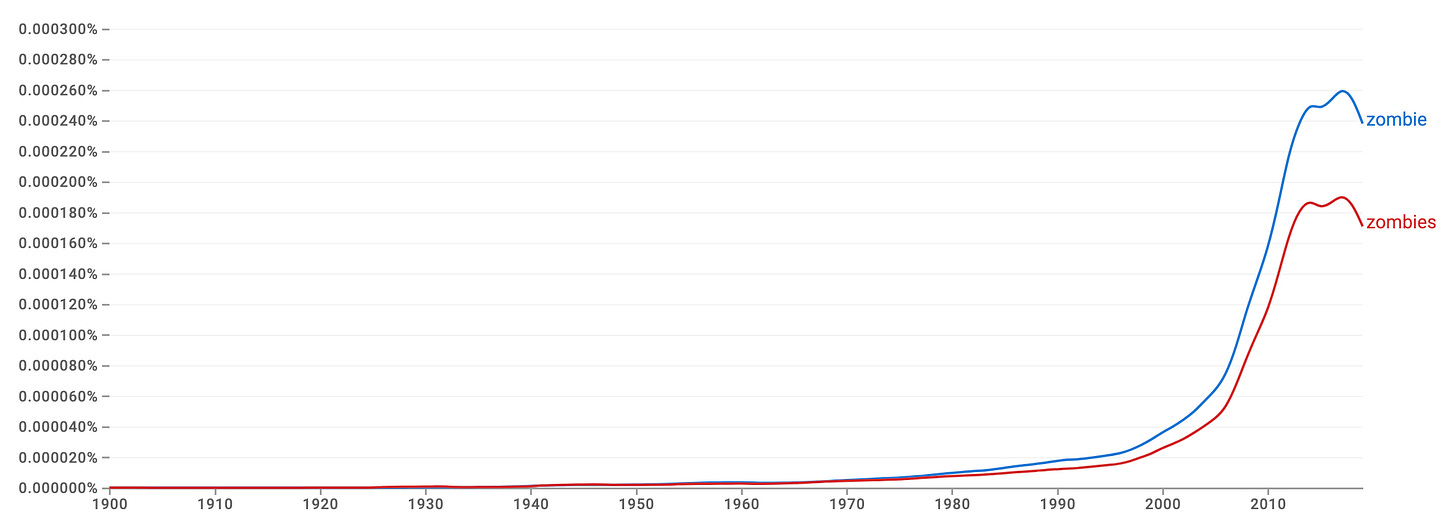

There will be more talk about zombies on here in the future, as zombies have been a major way in which post-apocalyptic stories have been and continue to be explored. As the Google Ngrams plot above makes clear, while zombie-themed films and books do go back a bit, the amount of zombie-lit in the early 2000s reached… epidemic proportions. Brooks’ book, in 2006, was published just before the point of over-saturation.

Marc Forster’s film adaptation of World War Z was not. Coming out at the peak of the zombie craze, in 2013, it might have contributed to the sense that it had been, er, done to death.2

Where Brooks’ book was a fun-but-serious attempt to use zombies as a way to explore the complexities that accompany real-world catastrophes, Forster’s film was… something else. Let’s leave aside how it works as a zombie movie — I’ll concede it has a few inspired scenes, embedded within what was otherwise a pretty uninspiring film.3 But as an adaptation, it was, in my view, an utter disaster.

Aside from having only the loosest of connections to any aspects of the source material, it managed to almost perfectly subvert and reject the underlying structure and message of the book. It’s a generic zombie film whose sole innovation is having its brawny heroic protagonist, played by Brad Pitt, visit a handful of other countries on his mission to find an instant cure to the zombie outbreak. Which (spoilers except it is bog-standard obvious) he does, which fixes the world overnight. I guess I could imagine even more perverse ways to disregard the source material — at least Pitt does travel a bit — but it’s still a pretty impressive fete, to so perfectly invert the message of the source material.

How and why did this happen? I don’t know. I imagine the conversation in the studio centered around ideas like “I bet a Brad Pitt zombie movie would make a lot of money” and “only nerds care about the source material, and they aren’t our target demographic for making lots of money.” Anyway, however it got that way, it took what was a very intelligent book and turned it into a very dumb movie.4

A question that has been going through my mind for a decade now is this: what would a good film adaptation of World War Z actually look like? By “good” I mean, “faithful to the original message of the book,” but I am also not ignorant of the fact that to be successful, much less actually get funded and made, such a film would have to conform to various Hollywood standards and expectations. A purely literal script based on the book would absolutely not work, because books aren’t films and films aren’t books. Great adaptations find a way to grasp the core of the original work and maintain that through the transmutation to the new medium, while at the same time adding elements and approaches that can only be accomplished in the new medium.5

I’ve come up with two possible answers to this. If you have pitches of your own, put them in the comments — I’m all ears, and this is something I think about every time I re-read World War Z, which is fairly often (because I like to contrive excuses to assign it to my students).

The first is to go back to the Terkel-esque aspect and how that is normally translated into film: as a documentary. So one version of this imaginary adaptation would be as a multi-part faux documentary, played totally straight, in the style of, for example, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War (2017). I really enjoyed the latter (which does not mean it is not without its flaws, critiques, etc.) because it takes the time to try and tell a lot of stories about the Vietnam War from a lot of different perspectives.6 And by time, I mean it is ten episodes long, and clocks in at over 17 hours. Which, of course, is much more than you could do for a feature film. But it would totally work as a streaming series, right?

Such an approach would let you really do Brooks’ approach justice, because you could essentially replicate the message of the book, including its conceit that we, the audience, also experienced the zombie apocalypse as well. (Also, imagine the possibilities for “in-universe” commercials.)

Of course, that’s a pretty radical reimagining, in terms of genre: not a “zombie film” that could play in the theaters, but a television series that would work better in the media landscape of today than that of when Forster’s film was made.

What if we wanted to achieve something better, but still through the lens of a standard, feature-length, blockbuster movie?

My second suggestion would be to have a film which wasn’t as multi-faceted as Brooks’ book, but wasn’t as narrowly-focused as the Brad Pitt picture. A model for this might be the 2011 film Contagion, which has multiple focal points/protagonists, each navigating totally disconnected paths through a world disaster simultaneously. Contagion still manages to conform to aspects of a Hollywood narrative (heroes, struggles, stars, etc.), but does so in a way that mostly doesn’t oversimplify in traditional fashion.7

I’ll write more about Contagion at a future time, as it’s another one that we no doubt “read” differently now having lived through a pandemic (and that I know a lot of us watched or rewatched during it), but for the purpose of thinking about World War Z, what works about it is exactly the way it conjures a “global” sense of the scale of the catastrophe, the lack of the “central male protagonist who fixes it all” trope, and, in what I think is its best aspect, the way it indicates that even after you get the “fix” (in this case, the vaccine), the roll-out time will still be impressive, and the overall effects of the disaster don’t just vanish.

If anything, the experience with COVID indicates how much further it could have gone with that, but I don’t know of any other disaster films that quite goes as far in that direction. It subverts the “happily ever after” trope and the “and then everything was fixed” tropes, both of which can be narratively satisfying, of course, but are deeply misleading when it comes to how real-world catastrophes play out.

OK, those are my pitches. If you’ve got other ideas, I’m all ears.8

For me, the reason this is an interesting question, aside from the fact that I like the Brooks book and was disappointed by its film adaptation, is that ultimately this isn’t just a question of how to do one book. What makes World War Z, the book, interesting is that it is about disaster and recovery, and takes a serious approach to both aspects of it. Most of our disaster and apocalypse media focus on the first part of that — and usually, the disaster is averted. When we have media that is about a non-averted disaster, it often jumps to a fully-destroyed (post-apocalyptic) world. World War Z is a book about going to the brink, losing a lot, and then slowly beginning the process of clawing one’s way back. It’s a lot closer to how disaster planners view these kinds of events, and how survivors experience them, than films about individual heroes or “magic” fixes.

So thinking about how to tell that kind of story well, in a way that is still palatable to large audiences, feels to me like a fairly important question. Because, as Brooks implicitly argues in the book, if you have a bad model for thinking about what global disasters look like, you’re going to have a hard time surviving them. And as the COVID experience quite plainly indicated… we’ve got a long way to go.

If you haven’t read any Studs Turkel, The Good War: An Oral History of World War II (1984) is both a great read and the obvious inspiration for World War Z. Though the historian in me winces at the amount of editing that must have been done and “quietly hidden” — it is just too readable — the overall effect is extremely compelling and many of the stories are undeniably fascinating.

But, of course, there are still zombie movies coming out, and zombie video games, today. So perhaps the zombie genre is… undead? Sorry. There are too many puns available here.

I think the beginning "zombies in traffic” sequence was pretty good, for example. It conjures up the uncertainty and panic that one would feel seeing such a thing from on the ground, unsure of what was going on. And the “zombies forming a pile” sequence was visually impressive, even if the overall sequence didn’t make a lot of sense within the story.

I got to meet Max Brooks once, years back, at a dinner event promoting a graphic novel he had written. He signed a copy of World War Z for me, which was kind, given that it wasn’t really what he was supposed to be promoting. I asked him what had happened with the film adaptation, and he very demurely smiled and shrugged. In my mind, I then imagined him jumping into a big vat of money, like Scrooge McDuck. Which is perhaps a bit unfair! I don’t blame him for the adaptation. I met a Hollywood screenwriter some time after, and posed my question about the adaptation to him, and he offered up that the only way such a book would be adapted well in modern Hollywood is if a) it became the passion project of someone with real Hollywood juice, or b) it had a massive and rabid fan-base who the executives feared alienating.

For me, the absolute best example of this is Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men and its adaptation by the Coen brothers. The movie and the book are two separate works of art, both based on a shared “core,” but the movie does things the book can’t do, and the book does things the movie can’t do. They’re both masterpieces in their own right. Whereas nobody says The Road is nearly as good of a film as the book… which is why I haven’t seen the film (and may never do so).

As an aside, I visited Vietnam (for tourism) last March, and one of our Vietnamese tour guides strongly recommended and endorsed Burns and Novick’s series to a group of tourists that included us (none of the others in this group were Americans, incidentally, and most seemed to have only the dimmest knowledge of the war itself). I thought that was really interesting.

It still has a “scientist who bravely and brilliantly saves the day on their own,” which is a tired trope, but it makes up for that, in my mind, by emphasizing how slow the roll-out of the vaccine would be in practice. Which, frustratingly, conformed very much to reality…

I’ll also do a quick shout-out to Like Stories of Old, a YouTuber who does thoughtful video essays on narrative and film that I enjoy quite a lot, and the Nebula-exclusive video he did in 2023 about what a satisfying sequel to World War Z would look like, which I thought was an interesting variation of the prompt I am using here.

For me the most interesting aspect of apocalyptic horror fiction is the response and recovery...providing the apocalypse is a credible one that allows for the possibility of human survival and eventual recovery (for instance a massive planetoid strike that reduces the whole surface of the planet to molten magma would be right out). That's why - as an example - although "The Road" struck a cord with me emotionally - I could not fully engage with the characters and their situation because I didn't understand what had brought their world low and why - years, apparently, after the triggering event - this situation for survivors was still so primitive and desperate. Same with the generally execrable "Walking Dead" universe of stories where the characters never did seem to learn how to overcome the issues of their new normal and spent a lot of time flailing uselessly about. Did the zombie virus preferentially kill anyone with an IQ over 90?

I've been in the headspace of a much more critical discussion of World War Z. You're not wrong with it's unique mechanical-narrative framing being a boon for cinema if replicated. That doesn't take away it's politics which is to put it mildly is a time capsule fusion of 2000's liberalism and 'reformist' doctrine. This to my mind makes "How are we going to adapt Yonkers and the Redeker plan?" a bigger question to ask any future adaptation rather than the ones you've already answered in this article.

To get back to the main topic: This considerations and discussion with more neutral space does lean me more towards the mini-series. The differences in research and locational negation should provide more peer review and updating on it's politics. My only nitpick is that the adaptation should have a mixture of hi-fi/lo-fi presentation distinct from the Burns style to both preserve the post-apocalyptic with new tech of the setting and the context of the interviewing breaking this work into it's own out of a neutral goverment report.